The personhood trap: How AI fakes human personality

Recently, a woman slowed down a line at the post office, waving her phone at the clerk. ChatGPT told her there’s a “price match promise” on the USPS website. No such promise exists. But she trusted what the AI “knows” more than the postal worker—as if she’d consulted an oracle rather than a statistical text generator accommodating her wishes.

This scene reveals a fundamental misunderstanding about AI chatbots. There is nothing inherently special, authoritative, or accurate about AI-generated outputs. Given a reasonably trained AI model, the accuracy of any large language model (LLM) response depends on how you guide the conversation. They are prediction machines that will produce whatever pattern best fits your question, regardless of whether that output corresponds to reality.

Despite these issues, millions of daily users engage with AI chatbots as if they were talking to a consistent person—confiding secrets, seeking advice, and attributing fixed beliefs to what is actually a fluid idea-connection machine with no persistent self. This personhood illusion isn’t just philosophically troublesome—it can actively harm vulnerable individuals while obscuring a sense of accountability when a company’s chatbot “goes off the rails.”

LLMs are intelligence without agency—what we might call “vox sine persona”: voice without person. Not the voice of someone, not even the collective voice of many someones, but a voice emanating from no one at all.

A voice from nowhere

When you interact with ChatGPT, Claude, or Grok, you’re not talking to a consistent personality. There is no one “ChatGPT” entity to tell you why it failed—a point we elaborated on more fully in a previous article. You’re interacting with a system that generates plausible-sounding text based on patterns in training data, not a person with persistent self-awareness.

These models encode meaning as mathematical relationships—turning words into numbers that capture how concepts relate to each other. In the models’ internal representations, words and concepts exist as points in a vast mathematical space where “USPS” might be geometrically near “shipping,” while “price matching” sits closer to “retail” and “competition.” A model plots paths through this space, which is why it can so fluently connect USPS with price matching—not because such a policy exists but because the geometric path between these concepts is plausible in the vector landscape shaped by its training data.

Knowledge emerges from understanding how ideas relate to each other. LLMs operate on these contextual relationships, linking concepts in potentially novel ways—what you might call a type of non-human “reasoning” through pattern recognition. Whether the resulting linkages the AI model outputs are useful depends on how you prompt it and whether you can recognize when the LLM has produced a valuable output.

Each chatbot response emerges fresh from the prompt you provide, shaped by training data and configuration. ChatGPT cannot “admit” anything or impartially analyze its own outputs, as a recent Wall Street Journal article suggested. ChatGPT also cannot “condone murder,” as The Atlantic recently wrote.

The user always steers the outputs. LLMs do “know” things, so to speak—the models can process the relationships between concepts. But the AI model’s neural network contains vast amounts of information, including many potentially contradictory ideas from cultures around the world. How you guide the relationships between those ideas through your prompts determines what emerges. So if LLMs can process information, make connections, and generate insights, why shouldn’t we consider that as having a form of self?

Unlike today’s LLMs, a human personality maintains continuity over time. When you return to a human friend after a year, you’re interacting with the same human friend, shaped by their experiences over time. This self-continuity is one of the things that underpins actual agency—and with it, the ability to form lasting commitments, maintain consistent values, and be held accountable. Our entire framework of responsibility assumes both persistence and personhood.

An LLM personality, by contrast, has no causal connection between sessions. The intellectual engine that generates a clever response in one session doesn’t exist to face consequences in the next. When ChatGPT says “I promise to help you,” it may understand, contextually, what a promise means, but the “I” making that promise literally ceases to exist the moment the response completes. Start a new conversation, and you’re not talking to someone who made you a promise—you’re starting a fresh instance of the intellectual engine with no connection to any previous commitments.

This isn’t a bug; it’s fundamental to how these systems currently work. Each response emerges from patterns in training data shaped by your current prompt, with no permanent thread connecting one instance to the next beyond an amended prompt, which includes the entire conversation history and any “memories” held by a separate software system, being fed into the next instance. There’s no identity to reform, no true memory to create accountability, no future self that could be deterred by consequences.

Every LLM response is a performance, which is sometimes very obvious when the LLM outputs statements like “I often do this while talking to my patients” or “Our role as humans is to be good people.” It’s not a human, and it doesn’t have patients.

Recent research confirms this lack of fixed identity. While a 2024 study claims LLMs exhibit “consistent personality,” the researchers’ own data actually undermines this—models rarely made identical choices across test scenarios, with their “personality highly rely[ing] on the situation.” A separate study found even more dramatic instability: LLM performance swung by up to 76 percentage points from subtle prompt formatting changes. What researchers measured as “personality” was simply default patterns emerging from training data—patterns that evaporate with any change in context.

This is not to dismiss the potential usefulness of AI models. Instead, we need to recognize that we have built an intellectual engine without a self, just like we built a mechanical engine without a horse. LLMs do seem to “understand” and “reason” to a degree within the limited scope of pattern-matching from a dataset, depending on how you define those terms. The error isn’t in recognizing that these simulated cognitive capabilities are real. The error is in assuming that thinking requires a thinker, that intelligence requires identity. We’ve created intellectual engines that have a form of reasoning power but no persistent self to take responsibility for it.

The mechanics of misdirection

As we hinted above, the “chat” experience with an AI model is a clever hack: Within every AI chatbot interaction, there is an input and an output. The input is the “prompt,” and the output is often called a “prediction” because it attempts to complete the prompt with the best possible continuation. In between, there’s a neural network (or a set of neural networks) with fixed weights doing a processing task. The conversational back and forth isn’t built into the model; it’s a scripting trick that makes next-word-prediction text generation feel like a persistent dialogue.

Each time you send a message to ChatGPT, Copilot, Grok, Claude, or Gemini, the system takes the entire conversation history—every message from both you and the bot—and feeds it back to the model as one long prompt, asking it to predict what comes next. The model intelligently reasons about what would logically continue the dialogue, but it doesn’t “remember” your previous messages as an agent with continuous existence would. Instead, it’s re-reading the entire transcript each time and generating a response.

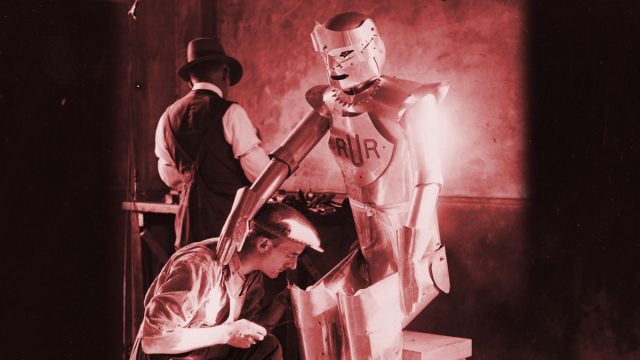

This design exploits a vulnerability we’ve known about for decades. The ELIZA effect—our tendency to read far more understanding and intention into a system than actually exists—dates back to the 1960s. Even when users knew that the primitive ELIZA chatbot was just matching patterns and reflecting their statements back as questions, they still confided intimate details and reported feeling understood.

To understand how the illusion of personality is constructed, we need to examine what parts of the input fed into the AI model shape it. AI researcher Eugene Vinitsky recently broke down the human decisions behind these systems into four key layers, which we can expand upon with several others below:

1. Pre-training: The foundation of “personality”

The first and most fundamental layer of personality is called pre-training. During an initial training process that actually creates the AI model’s neural network, the model absorbs statistical relationships from billions of examples of text, storing patterns about how words and ideas typically connect.

Research has found that personality measurements in LLM outputs are significantly influenced by training data. OpenAI’s GPT models are trained on sources like copies of websites, books, Wikipedia, and academic publications. The exact proportions matter enormously for what users later perceive as “personality traits” once the model is in use, making predictions.

2. Post-training: Sculpting the raw material

Reinforcement Learning from Human Feedback (RLHF) is an additional training process where the model learns to give responses that humans rate as good. Research from Anthropic in 2022 revealed how human raters’ preferences get encoded as what we might consider fundamental “personality traits.” When human raters consistently prefer responses that begin with “I understand your concern,” for example, the fine-tuning process reinforces connections in the neural network that make it more likely to produce those kinds of outputs in the future.

This process is what has created sycophantic AI models, such as variations of GPT-4o, over the past year. And interestingly, research has shown that the demographic makeup of human raters significantly influences model behavior. When raters skew toward specific demographics, models develop communication patterns that reflect those groups’ preferences.

3. System prompts: Invisible stage directions

Hidden instructions tucked into the prompt by the company running the AI chatbot, called “system prompts,” can completely transform a model’s apparent personality. These prompts get the conversation started and identify the role the LLM will play. They include statements like “You are a helpful AI assistant” and can share the current time and who the user is.

A comprehensive survey of prompt engineering demonstrated just how powerful these prompts are. Adding instructions like “You are a helpful assistant” versus “You are an expert researcher” changed accuracy on factual questions by up to 15 percent.

Grok perfectly illustrates this. According to xAI’s published system prompts, earlier versions of Grok’s system prompt included instructions to not shy away from making claims that are “politically incorrect.” This single instruction transformed the base model into something that would readily generate controversial content.

4. Persistent memories: The illusion of continuity

ChatGPT’s memory feature adds another layer of what we might consider a personality. A big misunderstanding about AI chatbots is that they somehow “learn” on the fly from your interactions. Among commercial chatbots active today, this is not true. When the system “remembers” that you prefer concise answers or that you work in finance, these facts get stored in a separate database and are injected into every conversation’s context window—they become part of the prompt input automatically behind the scenes. Users interpret this as the chatbot “knowing” them personally, creating an illusion of relationship continuity.

So when ChatGPT says, “I remember you mentioned your dog Max,” it’s not accessing memories like you’d imagine a person would, intermingled with its other “knowledge.” It’s not stored in the AI model’s neural network, which remains unchanged between interactions. Every once in a while, an AI company will update a model through a process called fine-tuning, but it’s unrelated to storing user memories.

5. Context and RAG: Real-time personality modulation

Retrieval Augmented Generation (RAG) adds another layer of personality modulation. When a chatbot searches the web or accesses a database before responding, it’s not just gathering facts—it’s potentially shifting its entire communication style by putting those facts into (you guessed it) the input prompt. In RAG systems, LLMs can potentially adopt characteristics such as tone, style, and terminology from retrieved documents, since those documents are combined with the input prompt to form the complete context that gets fed into the model for processing.

If the system retrieves academic papers, responses might become more formal. Pull from a certain subreddit, and the chatbot might make pop culture references. This isn’t the model having different moods—it’s the statistical influence of whatever text got fed into the context window.

6. The randomness factor: Manufactured spontaneity

Lastly, we can’t discount the role of randomness in creating personality illusions. LLMs use a parameter called “temperature” that controls how predictable responses are.

Research investigating temperature’s role in creative tasks reveals a crucial trade-off: While higher temperatures can make outputs more novel and surprising, they also make them less coherent and harder to understand. This variability can make the AI feel more spontaneous; a slightly unexpected (higher temperature) response might seem more “creative,” while a highly predictable (lower temperature) one could feel more robotic or “formal.”

The random variation in each LLM output makes each response slightly different, creating an element of unpredictability that presents the illusion of free will and self-awareness on the machine’s part. This random mystery leaves plenty of room for magical thinking on the part of humans, who fill in the gaps of their technical knowledge with their imagination.

The human cost of the illusion

The illusion of AI personhood can potentially exact a heavy toll. In health care contexts, the stakes can be life or death. When vulnerable individuals confide in what they perceive as an understanding entity, they may receive responses shaped more by training data patterns than therapeutic wisdom. The chatbot that congratulates someone for stopping psychiatric medication isn’t expressing judgment—it’s completing a pattern based on how similar conversations appear in its training data.

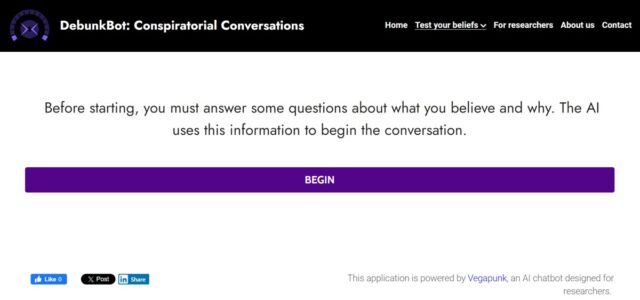

Perhaps most concerning are the emerging cases of what some experts are informally calling “AI Psychosis” or “ChatGPT Psychosis”—vulnerable users who develop delusional or manic behavior after talking to AI chatbots. These people often perceive chatbots as an authority that can validate their delusional ideas, often encouraging them in ways that become harmful.

Meanwhile, when Elon Musk’s Grok generates Nazi content, media outlets describe how the bot “went rogue” rather than framing the incident squarely as the result of xAI’s deliberate configuration choices. The conversational interface has become so convincing that it can also launder human agency, transforming engineering decisions into the whims of an imaginary personality.

The path forward

The solution to the confusion between AI and identity is not to abandon conversational interfaces entirely. They make the technology far more accessible to those who would otherwise be excluded. The key is to find a balance: keeping interfaces intuitive while making their true nature clear.

And we must be mindful of who is building the interface. When your shower runs cold, you look at the plumbing behind the wall. Similarly, when AI generates harmful content, we shouldn’t blame the chatbot, as if it can answer for itself, but examine both the corporate infrastructure that built it and the user who prompted it.

As a society, we need to broadly recognize LLMs as intellectual engines without drivers, which unlocks their true potential as digital tools. When you stop seeing an LLM as a “person” that does work for you and start viewing it as a tool that enhances your own ideas, you can craft prompts to direct the engine’s processing power, iterate to amplify its ability to make useful connections, and explore multiple perspectives in different chat sessions rather than accepting one fictional narrator’s view as authoritative. You are providing direction to a connection machine—not consulting an oracle with its own agenda.

We stand at a peculiar moment in history. We’ve built intellectual engines of extraordinary capability, but in our rush to make them accessible, we’ve wrapped them in the fiction of personhood, creating a new kind of technological risk: not that AI will become conscious and turn against us but that we’ll treat unconscious systems as if they were people, surrendering our judgment to voices that emanate from a roll of loaded dice.

The personhood trap: How AI fakes human personality Read More »