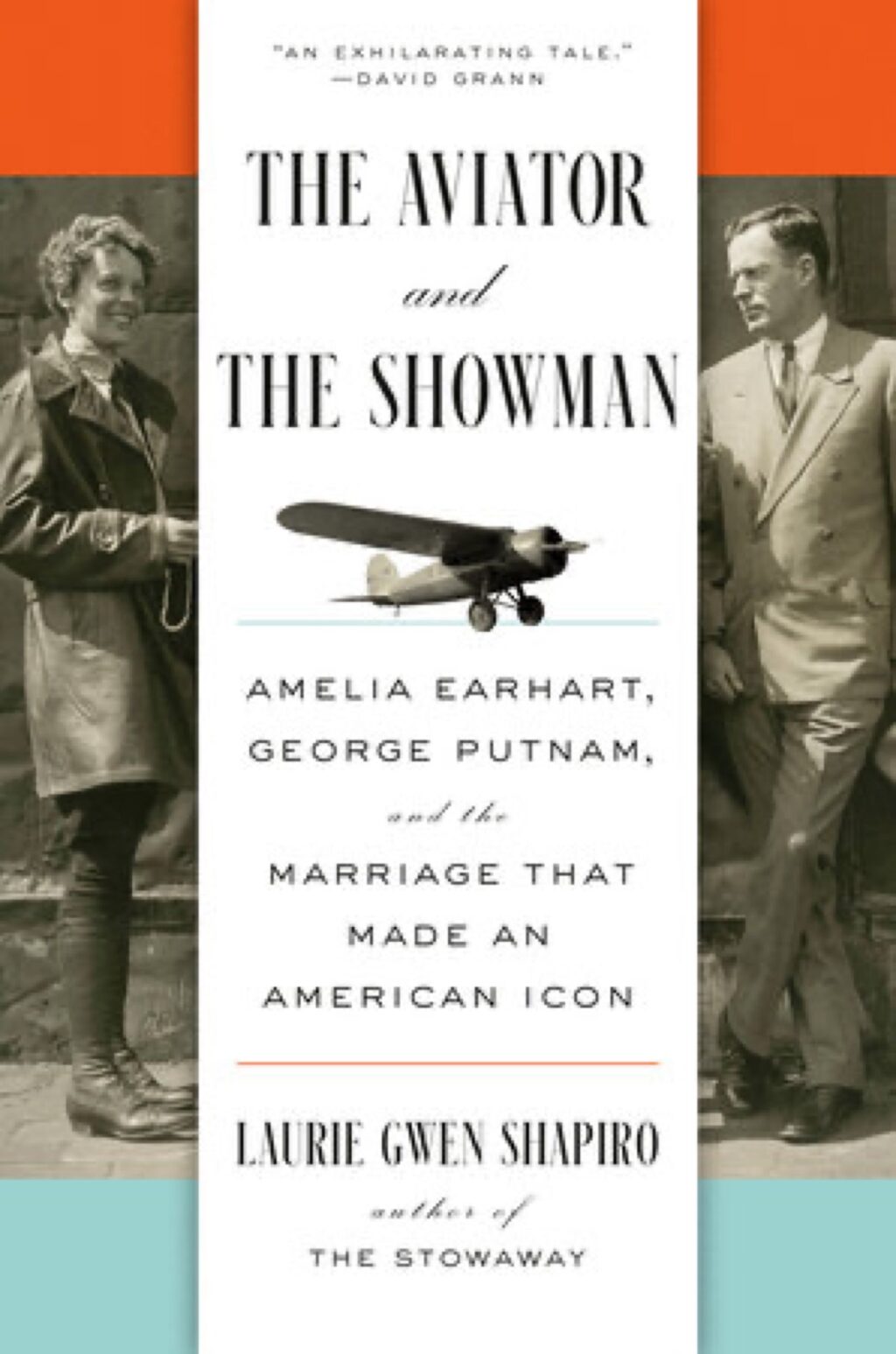

New Amelia Earhart bio delves into her unconventional marriage

more than a marriage of convenience

Author Laurie Gwen Shapiro chats with Ars about her latest book, The Aviator and the Showman.

Amelia Earhart. Credit: Public domain

Famed aviator Amelia Earhart has captured our imaginations for nearly a century, particularly her disappearance in 1937 during an attempt to become the first female pilot to circumnavigate the globe. Earhart was a complicated woman, highly skilled as a pilot yet with a tendency toward carelessness. And her marriage to a flamboyant publisher with a flair for marketing may have encouraged that carelessness and contributed to her untimely demise, according to a fascinating new book, The Aviator and the Showman: Amelia Earhart, George Putnam, and the Marriage that Made an American Icon.

Author Laurie Gwen Shapiro is a longtime Earhart fan. A documentary filmmaker and journalist, she first read about Earhart in a short biography distributed by Scholastic Books. “I got a little obsessed with her when I was younger,” Shapiro told Ars. The fascination faded as she got older and launched her own career. But she rediscovered her passion for Earhart while writing her 2018 book, The Stowaway, about a young man who stowed away on Admiral Richard Byrd‘s first voyage to Antarctica. The marketing mastermind behind the boy’s journey and his subsequent (ghost-written) memoir was publisher George Palmer Putnam, Earhart’s eventual husband.

The fact that Earhart started out as Putnam’s mistress contradicted Shapiro’s early squeaky-clean image of Earhart and drove her to delve deeper into the life of this extraordinary woman. “I was less interested in how she died than how she lived,” said Shapiro. “Was she a good pilot? Was she a good, kind person? Was this a real marriage? The mystery of Amelia Earhart is not how she died, but how she lived.”

There have been numerous Earhart biographies, but Shapiro accessed some relatively new source material, most notably a good 200 hours of tapes that had become available via the Smithsonian’s Amelia Earhart Project, including interviews with Earhart’s sister, Muriel. “I took an extra six months on my book just so that I could listen to all of them,” said Shapiro. She also scoured archival material at the University of New Hampshire concerning Putnam’s close associate, Hilton Railey; at Purdue University; and at Harvard’s Radcliffe Institute, along with numerous in-person interviews—including several with authors of prior Earhart biographies.

Shapiro’s breezy account of Earhart’s early life includes a few new details, particularly about the aviator’s relationship with an early benefactor (Shapiro calls him Earhart’s “sugar daddy”) in California: a 63-year-old billboard magnate named Thomas Humphrey Bennett Varney. Varney wanted to marry her, but she ended up accepting the proposal of a young chemical engineer from Boston, Samuel Chapman. “Amelia could have had a very different life,” said Shapiro. “She could have gone to Marblehead, Massachusetts, where [Chapman] had a house, and become part of the yacht set and she still would have had an interesting life. But I don’t think that was the life Amelia Earhart wanted, even if that meant she had a shorter life.”

Shapiro doesn’t neglect Putnam’s story, describing him as the “PT Barnum of publishing.” The family publishing company, G.P. Putnam and Sons, was founded in 1838 by his grandfather, and by the late 1920s, the ambitious young George was among several possible successors jockeying for position to replace his uncle, George Haven Putnam. He had his own ambitions, determined to bring what he viewed as a stodgy company fully into the 20th century.

Putnam published Charles Lindbergh‘s blockbuster memoir, We, in 1927 and followed that early success with a series of rather lurid adventure memoirs chronicling the exploits of “boy explorers.” The boys didn’t always survive their adventures, with one perishing from a snake bite and another drowning in a Bolivian flood. But the books were commercial successes, so Putnam kept cranking them out.

After Lindbergh’s historic crossing, Putnam was eager to tap into the public’s thirst for aviation stories. It wouldn’t be especially newsworthy to have another man make the same flight. But a woman? Putnam liked that idea, and a wealthy benefactor, steel heiress Amy Phipps Guest, provided financial support for the feat—really more of a publicity stunt, since Putnam’s plan, as always, was to publish a scintillating memoir of the journey. During the Jazz Age, newspapers routinely paid for exclusive rights to these kinds of stories in exchange for glowing coverage, per Shapiro. In this case, The New York Times did not initially want to sponsor a woman for a trans-Atlantic flight, but Putnam’s connections won them over.

Love at first sight

Earhart, then a social worker living in Boston, interviewed to be part of the three-person crew making that historic 1928 trans-Atlantic flight, and Putnam quickly spotted her potential to be his new adventure heroine. Railey later recalled that, at least for Putnam—whose marriage to Crayola heiress Dorothy Binney was floundering—it was love at first sight.

At the time, Earhart was still engaged to Chapman, and George was still married to Binney, but nonetheless, he “relentlessly pursued” Earhart. Earhart ended her engagement to Chapman in November 1928. “There’s a tape in the Smithsonian archives that talks about his wife coming in and catching them in sexual relations,” said Shapiro. “But [Binney] was having an affair, too, with a young man named George Weymouth [her son’s tutor]. This is the Jazz Age, anything goes. Amelia wanted to be able to achieve her dreams. Who are we to say a woman can’t marry a man who can give her a path to being wealthy?”

The successful 1928 flight earned Earhart the moniker “Lady Lindy.” Putnam showered his mistress with fur coats, sporty cars, and other luxurious trappings—although as her manager, he still kept 10 percent of her earnings. That life of luxury fell apart in October 1929 with the onset of the Great Depression, and Putnam found himself scrambling financially after being pushed out of the family publishing company.

Earhart and Putnam in 1931. Public domain

After his rather messy divorce from Binney, Putnam married Earhart in 1931. Earhart held decidedly unconventional views on marriage for that era: They held separate bank accounts, and she kept her maiden name, viewing the marriage as a “partnership” with “dual control,” and insisting in a letter to Putnam on their wedding day that she would not require fidelity. “I may have to keep some place where I can go to be myself, now and then, for I cannot guarantee to endure at all times the confinement of even an attractive cage,” she wrote.

Since money was tight, Putnam encouraged Earhart to go on the lecture circuit. Earhart would execute a stunt flight, write a book about it, and then go on a lecture tour. “This is an actual marriage,” said Shapiro. “It might have started out more romantically, but at a certain point, they needed each other in a partnership to survive. We don’t have fairy tale connections. Sometimes we have a hot romance that turns into a partnership and then cycles back into intense closeness and mental separation. I think that was the case with Amelia and George.”

Then came Earhart’s fateful final fight. The night before her scheduled departure, a nervous Earhart wanted to wait, but Putnam already had plans in the works for yet another flight, financed through sponsorship deals. And he wanted to get the resulting book about the current pending flight out in time for Christmas. He convinced her to take off as planned. Her navigator, Fred Noonan, was good at his job, but he was a heavy drinker, so he came cheap. That decision was one of several that would prove costly.

Shapiro describes this flight as being “plagued with mechanical issues from the start, underprepared and over-hyped, a feat of marketing more than a feat of engineering.” And she does not absolve Earhart from blame. “She refused to learn Morse code,” said Shapiro. “She refused to hear that trying to land on Howland Island was almost a suicide mission. It’s almost certain that she ran out of gas. Amelia was a very good person, a decent flyer, and beyond brave. She brought up women and championed feminism when other technically more gifted women pilots were going for solo records and had no time for their peers. She aided the aviation industry during the Great Depression as a likable ambassador of the air.”

However, Shapiro believes that Earhart’s marriage to Putnam amplified her incautious impulses, with tragic consequences on her final flight. “Is it George’s fault, or is it Amelia’s fault? I don’t think that’s fair to say,” she said. In many ways, the two complemented each other. Like Putnam, Earhart had great ambition, and her marriage to Putnam enabled her to achieve her goals.

The flip side is that they also brought out each other’s less positive attributes. “They were both aware of the risks involved in what they were doing,” Shapiro said. “But I also tried to show that there was a pattern of both of them taking extraordinary risks without really worrying about critical details. Yes, there is tremendous bravery in [undertaking] all these flights, but bravery is not always enough when charisma trumps caution—and when the showman insists the show must go on.”

Jennifer is a senior writer at Ars Technica with a particular focus on where science meets culture, covering everything from physics and related interdisciplinary topics to her favorite films and TV series. Jennifer lives in Baltimore with her spouse, physicist Sean M. Carroll, and their two cats, Ariel and Caliban.

New Amelia Earhart bio delves into her unconventional marriage Read More »