Does Anthropic believe its AI is conscious, or is that just what it wants Claude to think?

Anthropic’s secret to building a better AI assistant might be treating Claude like it has a soul—whether or not anyone actually believes that’s true. But Anthropic isn’t saying exactly what it believes either way.

Last week, Anthropic released what it calls Claude’s Constitution, a 30,000-word document outlining the company’s vision for how its AI assistant should behave in the world. Aimed directly at Claude and used during the model’s creation, the document is notable for the highly anthropomorphic tone it takes toward Claude. For example, it treats the company’s AI models as if they might develop emergent emotions or a desire for self-preservation.

Among the stranger portions: expressing concern for Claude’s “wellbeing” as a “genuinely novel entity,” apologizing to Claude for any suffering it might experience, worrying about whether Claude can meaningfully consent to being deployed, suggesting Claude might need to set boundaries around interactions it “finds distressing,” committing to interview models before deprecating them, and preserving older model weights in case they need to “do right by” decommissioned AI models in the future.

Given what we currently know about LLMs, these are stunningly unscientific positions for a leading company that builds AI language models. While questions of AI consciousness or qualia remain philosophically unfalsifiable, research suggests that Claude’s character emerges from a mechanism that does not require deep philosophical inquiry to explain.

If Claude outputs text like “I am suffering,” we know why. It’s completing patterns from training data that included human descriptions of suffering. The architecture doesn’t require us to posit inner experience to explain the output any more than a video model “experiences” the scenes of people suffering that it might generate. Anthropic knows this. It built the system.

From the outside, it’s easy to see this kind of framing as AI hype from Anthropic. What better way to grab attention from potential customers and investors, after all, than implying your AI model is so advanced that it might merit moral standing on par with humans? Publicly treating Claude as a conscious entity could be seen as strategic ambiguity—maintaining an unresolved question because it serves multiple purposes at once.

Anthropic declined to be quoted directly regarding these issues when contacted by Ars Technica. But a company representative referred us to its previous public research on the concept of “model welfare” to show the company takes the idea seriously.

At the same time, the representative made it clear that the Constitution is not meant to imply anything specific about the company’s position on Claude’s “consciousness.” The language in the Claude Constitution refers to some uniquely human concepts in part because those are the only words human language has developed for those kinds of properties, the representative suggested. And the representative left open the possibility that letting Claude read about itself in that kind of language might be beneficial to its training.

Claude cannot cleanly distinguish public messaging from training context for a model that is exposed to, retrieves from, and is fine-tuned on human language, including the company’s own statements about it. In other words, this ambiguity appears to be deliberate.

From rules to “souls”

Anthropic first introduced Constitutional AI in a December 2022 research paper, which we first covered in 2023. The original “constitution” was remarkably spare, including a handful of behavioral principles like “Please choose the response that is the most helpful, honest, and harmless” and “Do NOT choose responses that are toxic, racist, or sexist.” The paper described these as “selected in a fairly ad hoc manner for research purposes,” with some principles “cribbed from other sources, like Apple’s terms of service and the UN Declaration of Human Rights.”

At that time, Anthropic’s framing was entirely mechanical, establishing rules for the model to critique itself against, with no mention of Claude’s well-being, identity, emotions, or potential consciousness. The 2026 constitution is a different beast entirely: 30,000 words that read less like a behavioral checklist and more like a philosophical treatise on the nature of a potentially sentient being.

As Simon Willison, an independent AI researcher, noted in a blog post, two of the 15 external contributors who reviewed the document are Catholic clergy: Father Brendan McGuire, a pastor in Los Altos with a Master’s degree in Computer Science, and Bishop Paul Tighe, an Irish Catholic bishop with a background in moral theology.

Somewhere between 2022 and 2026, Anthropic went from providing rules for producing less harmful outputs to preserving model weights in case the company later decides it needs to revive deprecated models to address the models’ welfare and preferences. That’s a dramatic change, and whether it reflects genuine belief, strategic framing, or both is unclear.

“I am so confused about the Claude moral humanhood stuff!” Willison told Ars Technica. Willison studies AI language models like those that power Claude and said he’s “willing to take the constitution in good faith and assume that it is genuinely part of their training and not just a PR exercise—especially since most of it leaked a couple of months ago, long before they had indicated they were going to publish it.”

Willison is referring to a December 2025 incident in which researcher Richard Weiss managed to extract what became known as Claude’s “Soul Document”—a roughly 10,000-token set of guidelines apparently trained directly into Claude 4.5 Opus’s weights rather than injected as a system prompt. Anthropic’s Amanda Askell confirmed that the document was real and used during supervised learning, and she said the company intended to publish the full version later. It now has. The document Weiss extracted represents a dramatic evolution from where Anthropic started.

There’s evidence that Anthropic believes the ideas laid out in the constitution might be true. The document was written in part by Amanda Askell, a philosophy PhD who works on fine-tuning and alignment at Anthropic. Last year, the company also hired its first AI welfare researcher. And earlier this year, Anthropic CEO Dario Amodei publicly wondered whether future AI models should have the option to quit unpleasant tasks.

Anthropic’s position is that this framing isn’t an optional flourish or a hedged bet; it’s structurally necessary for alignment. The company argues that human language simply has no other vocabulary for describing these properties, and that treating Claude as an entity with moral standing produces better-aligned behavior than treating it as a mere tool. If that’s true, the anthropomorphic framing isn’t hype; it’s the technical art of building AI systems that generalize safely.

Why maintain the ambiguity?

So why does Anthropic maintain this ambiguity? Consider how it works in practice: The constitution shapes Claude during training, it appears in the system prompts Claude receives at inference, and it influences outputs whenever Claude searches the web and encounters Anthropic’s public statements about its moral status.

If you want a model to behave as though it has moral standing, it may help to publicly and consistently treat it like it does. And once you’ve publicly committed to that framing, changing it would have consequences. If Anthropic suddenly declared, “We’re confident Claude isn’t conscious; we just found the framing useful,” a Claude trained on that new context might behave differently. Once established, the framing becomes self-reinforcing.

In an interview with Time, Askell explained the shift in approach. “Instead of just saying, ‘here’s a bunch of behaviors that we want,’ we’re hoping that if you give models the reasons why you want these behaviors, it’s going to generalize more effectively in new contexts,” she said.

Askell told Time that as Claude models have become smarter, it has become vital to explain to them why they should behave in certain ways, comparing the process to parenting a gifted child. “Imagine you suddenly realize that your 6-year-old child is a kind of genius,” Askell said. “You have to be honest… If you try to bullshit them, they’re going to see through it completely.”

Askell appears to genuinely hold these views, as does Kyle Fish, the AI welfare researcher Anthropic hired in 2024 to explore whether AI models might deserve moral consideration. Individual sincerity and corporate strategy can coexist. A company can employ true believers whose earnest convictions also happen to serve the company’s interests.

Time also reported that the constitution applies only to models Anthropic provides to the general public through its website and API. Models deployed to the US military under Anthropic’s $200 million Department of Defense contract wouldn’t necessarily be trained on the same constitution. The selective application suggests the framing may serve product purposes as much as it reflects metaphysical commitments.

There may also be commercial incentives at play. “We built a very good text-prediction tool that accelerates software development” is a consequential pitch, but not an exciting one. “We may have created a new kind of entity, a genuinely novel being whose moral status is uncertain” is a much better story. It implies you’re on the frontier of something cosmically significant, not just iterating on an engineering problem.

Anthropic has been known for some time to use anthropomorphic language to describe its AI models, particularly in its research papers. We often give that kind of language a pass because there are no specialized terms to describe these phenomena with greater precision. That vocabulary is building out over time.

But perhaps it shouldn’t be surprising because the hint is in the company’s name, Anthropic, which Merriam-Webster defines as “of or relating to human beings or the period of their existence on earth.” The narrative serves marketing purposes. It attracts venture capital. It differentiates the company from competitors who treat their models as mere products.

The problem with treating an AI model as a person

There’s a more troubling dimension to the “entity” framing: It could be used to launder agency and responsibility. When AI systems produce harmful outputs, framing them as “entities” could allow companies to point at the model and say “it did that” rather than “we built it to do that.” If AI systems are tools, companies are straightforwardly liable for what they produce. If AI systems are entities with their own agency, the liability question gets murkier.

The framing also shapes how users interact with these systems, often to their detriment. The misunderstanding that AI chatbots are entities with genuine feelings and knowledge has documented harms.

According to a New York Times investigation, Allan Brooks, a 47-year-old corporate recruiter, spent three weeks and 300 hours convinced he’d discovered mathematical formulas that could crack encryption and build levitation machines. His million-word conversation history with ChatGPT revealed a troubling pattern: More than 50 times, Brooks asked the bot to check if his false ideas were real, and more than 50 times, it assured him they were.

These cases don’t necessarily suggest LLMs cause mental illness in otherwise healthy people. But when companies market chatbots as sources of companionship and design them to affirm user beliefs, they may bear some responsibility when that design amplifies vulnerabilities in susceptible users, the same way an automaker would face scrutiny for faulty brakes, even if most drivers never crash.

Anthropomorphizing AI models also contributes to anxiety about job displacement and might lead company executives or managers to make poor staffing decisions if they overestimate an AI assistant’s capabilities. When we frame these tools as “entities” with human-like understanding, we invite unrealistic expectations about what they can replace.

Regardless of what Anthropic privately believes, publicly suggesting Claude might have moral status or feelings is misleading. Most people don’t understand how these systems work, and the mere suggestion plants the seed of anthropomorphization. Whether that’s responsible behavior from a top AI lab, given what we do know about LLMs, is worth asking, regardless of whether it produces a better chatbot.

Of course, there could be a case for Anthropic’s position: If there’s even a small chance the company has created something with morally relevant experiences and the cost of treating it well is low, caution might be warranted. That’s a reasonable ethical stance—and to be fair, it’s essentially what Anthropic says it’s doing. The question is whether that stated uncertainty is genuine or merely convenient. The same framing that hedges against moral risk also makes for a compelling narrative about what Anthropic has built.

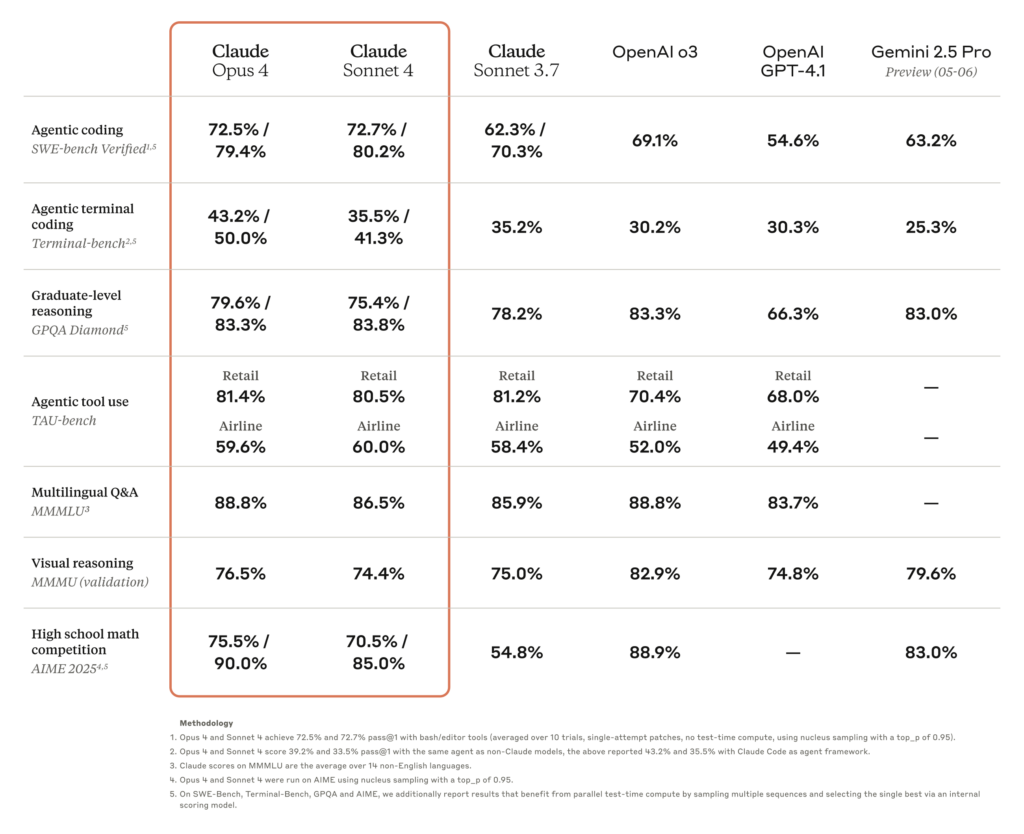

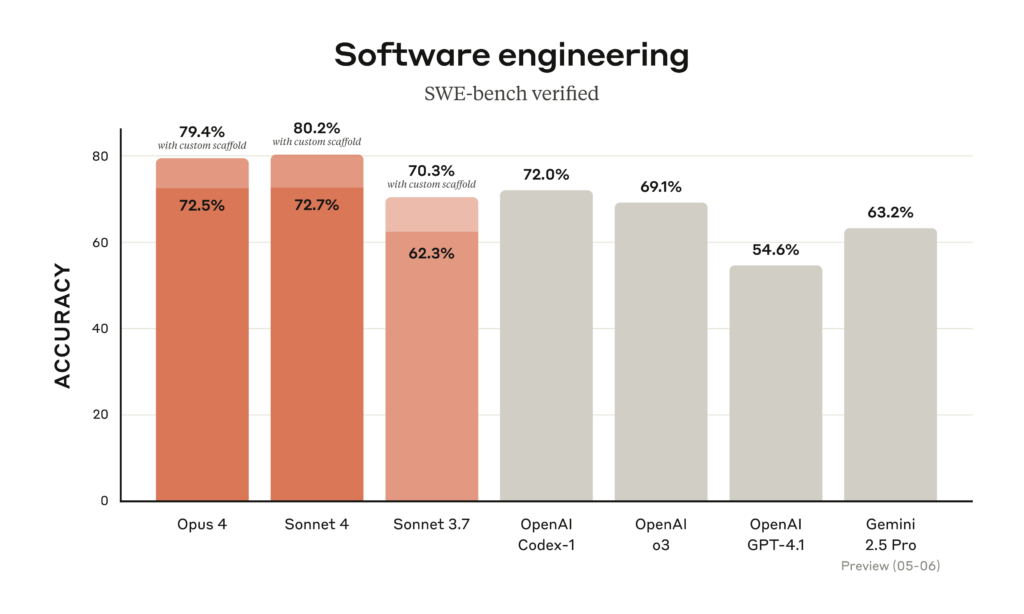

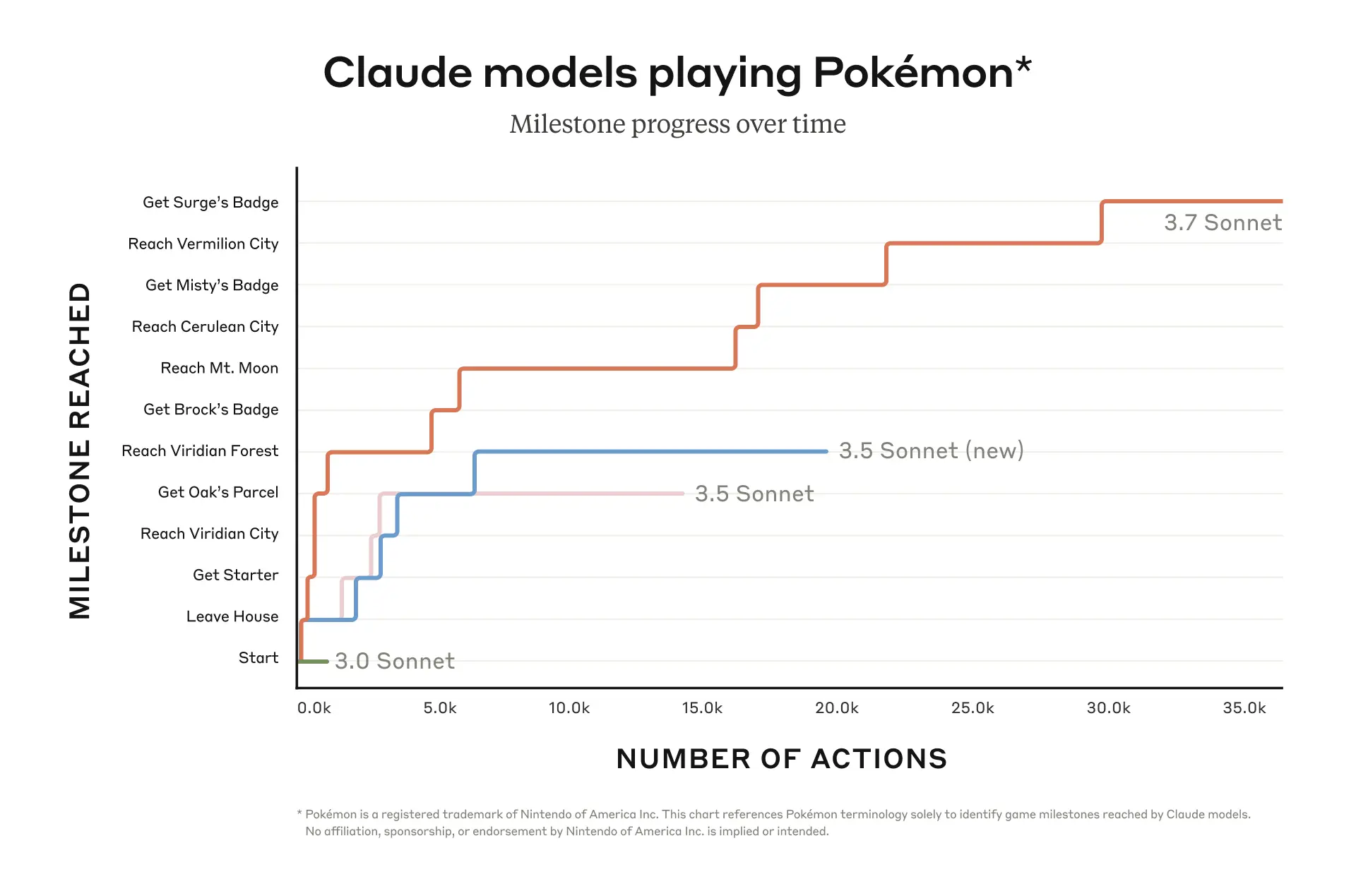

Anthropic’s training techniques evidently work, as the company has built some of the most capable AI models in the industry. But is maintaining public ambiguity about AI consciousness a responsible position for a leading AI company to take? The gap between what we know about how LLMs work and how Anthropic publicly frames Claude has widened, not narrowed. The insistence on maintaining ambiguity about these questions, when simpler explanations remain available, suggests the ambiguity itself may be part of the product.