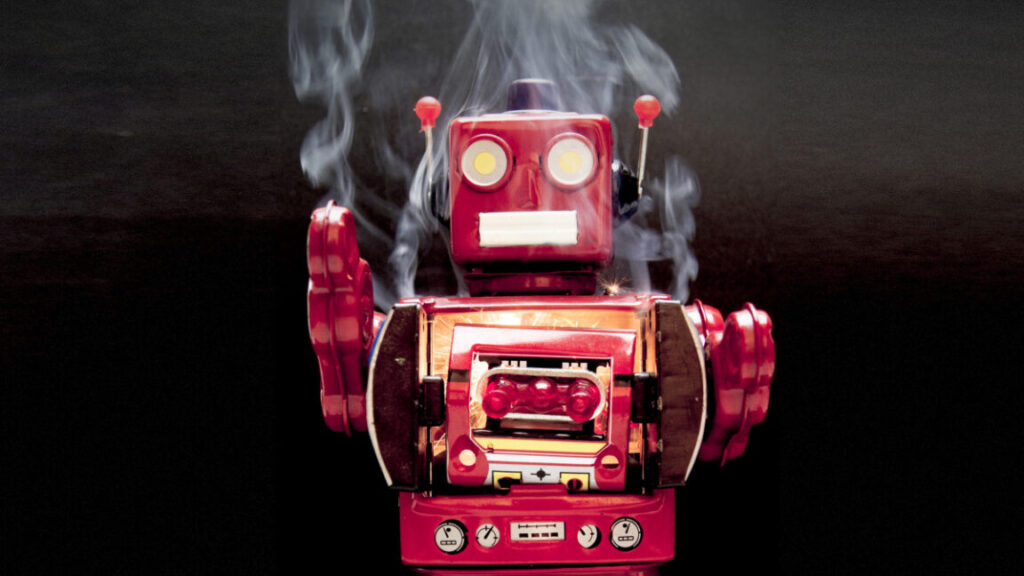

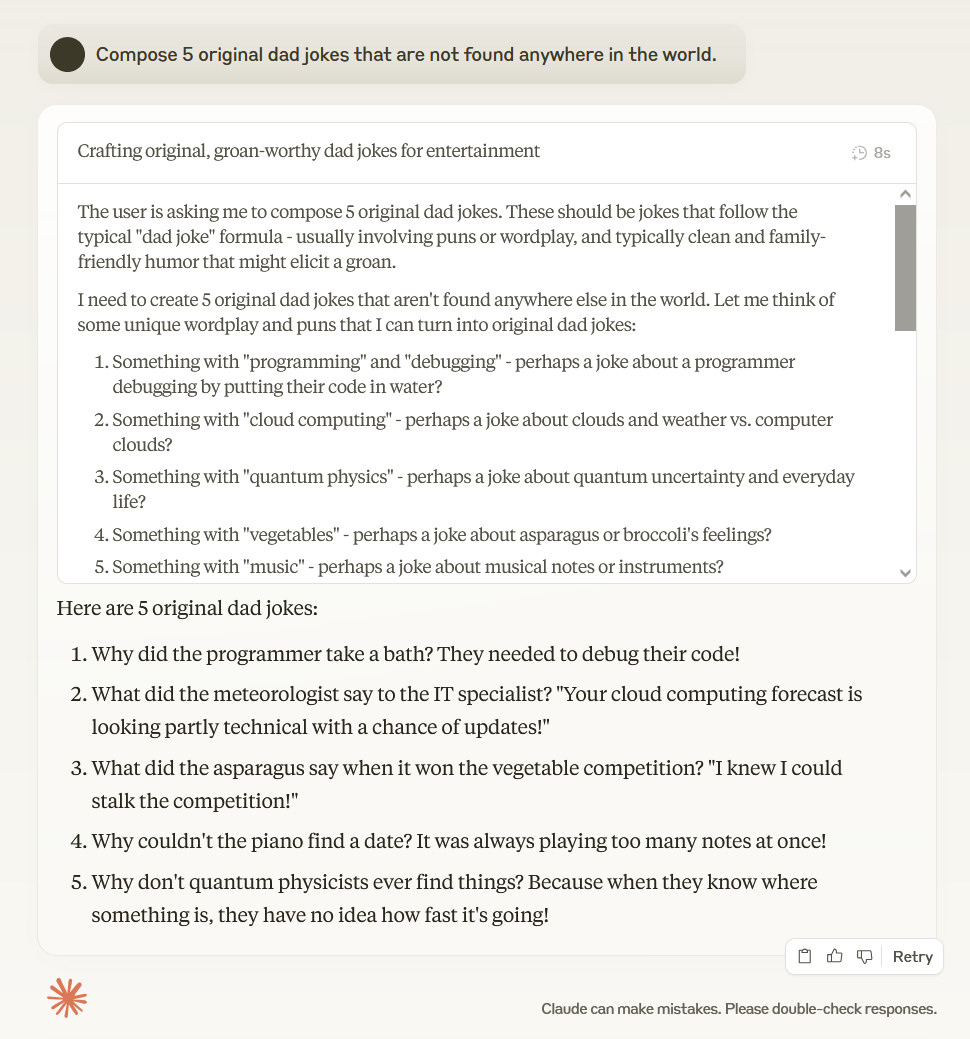

Hidden AI instructions reveal how Anthropic controls Claude 4

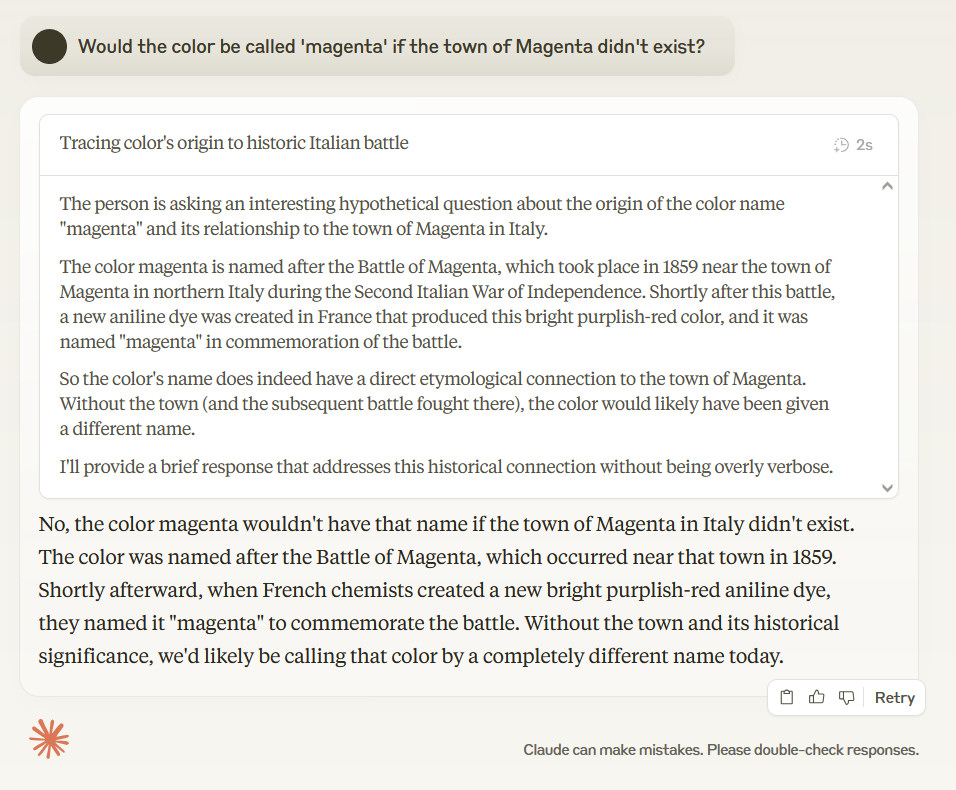

Willison, who coined the term “prompt injection” in 2022, is always on the lookout for LLM vulnerabilities. In his post, he notes that reading system prompts reminds him of warning signs in the real world that hint at past problems. “A system prompt can often be interpreted as a detailed list of all of the things the model used to do before it was told not to do them,” he writes.

Fighting the flattery problem

Willison’s analysis comes as AI companies grapple with sycophantic behavior in their models. As we reported in April, ChatGPT users have complained about GPT-4o’s “relentlessly positive tone” and excessive flattery since OpenAI’s March update. Users described feeling “buttered up” by responses like “Good question! You’re very astute to ask that,” with software engineer Craig Weiss tweeting that “ChatGPT is suddenly the biggest suckup I’ve ever met.”

The issue stems from how companies collect user feedback during training—people tend to prefer responses that make them feel good, creating a feedback loop where models learn that enthusiasm leads to higher ratings from humans. As a response to the feedback, OpenAI later rolled back ChatGPT’s 4o model and altered the system prompt as well, something we reported on and Willison also analyzed at the time.

One of Willison’s most interesting findings about Claude 4 relates to how Anthropic has guided both Claude models to avoid sycophantic behavior. “Claude never starts its response by saying a question or idea or observation was good, great, fascinating, profound, excellent, or any other positive adjective,” Anthropic writes in the prompt. “It skips the flattery and responds directly.”

Other system prompt highlights

The Claude 4 system prompt also includes extensive instructions on when Claude should or shouldn’t use bullet points and lists, with multiple paragraphs dedicated to discouraging frequent list-making in casual conversation. “Claude should not use bullet points or numbered lists for reports, documents, explanations, or unless the user explicitly asks for a list or ranking,” the prompt states.

Hidden AI instructions reveal how Anthropic controls Claude 4 Read More »