Studies pin down exactly when humans and Neanderthals swapped DNA

We may owe our tiny sliver of Neanderthal DNA to just a couple of hundred Neanderthals.

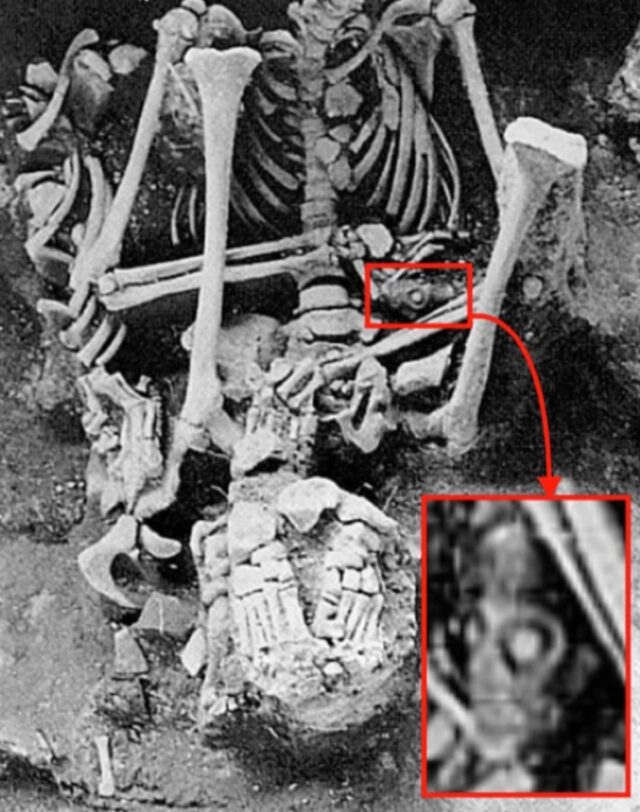

The artist’s illustration shows what the six people buried at the Ranis site, who lived between 49, 500 and 41,000 years ago, may have looked like. Two of these people are mother and daughter, and the mother is a distant cousin (or perhaps a great-great-grandparent or great-great-grandchild) to a woman whose skull was found 130 kilometers away in what’s now Czechia. Credit: Sumer et al. 2024

Two recent studies suggest that the gene flow (as the young people call it these days) between Neanderthals and our species happened during a short period sometime between 50,000 and 43,500 years ago. The studies, which share several co-authors, suggest that our torrid history with Neanderthals may have been shorter than we thought.

Pinpointing exactly when Neanderthals met H. sapiens

Max Planck Institute of Evolutionary Anthropology scientist Leonardo Iasi and his colleagues examined the genomes of 59 people who lived in Europe between 45,000 and 2,200 years ago, plus those of 275 modern people whose ancestors hailed from all over the world. The researchers cataloged the segments of Neanderthal DNA in each person’s genome, then compared them to see where those segments appeared and how that changed over time and distance. This revealed how Neanderthal ancestry got passed around as people spread around the world and provided an estimate of when it all started.

“We tried to compare where in the genomes these [Neanderthal segments] occur and if the positions are shared among individuals or if there are many unique segments that you find [in people from different places],” said University of California Berkeley geneticist Priya Moorjani in a recent press conference. “We find the majority of the segments are shared, and that would be consistent with the fact that there was a single gene flow event.”

That event wasn’t quite a one-night stand; in this case, a “gene flow event” is a period of centuries or millennia when Neanderthals and Homo sapiens must have been in close contact (obviously very close, in some cases). Iasi and his colleagues’ results suggest that happened between 50,500 and 43,000 years ago. But it’s quite different from our history with another closely related hominin species, the now-extinct Denisovans, with whom different Homo sapiens groups met and mingled at least twice on our way to taking over the world.

In a second study, Arev Sümer (also of the Max Planck Institute) and her colleagues found something very similar in the genomes of people who lived 49,500 to 41,000 years ago in what’s now the area around Ranis, Germany. The Ranis population, based on how their genomes compare to other ancient and modern people, seem to have been part of one of the first groups to split off from the wave of humans who migrated out of Africa, through the Levant, and into Eurasia sometime around 50,000 years ago. They carried with them traces of what their ancestors had gotten up to during that journey: about 2.9 percent of their genomes were made up of segments of Neanderthal ancestry.

Based on how long the Ranis people’s segments of Neanderthal DNA were (longer chunks of Neanderthal ancestry tend to point to more recent mixing), the interspecies mingling happened about 80 generations, or about 2,300 years, before the Ranis people lived and died. That’s about 49,000 to 45,000 years ago. The dates from both studies line up well with each other and with archaeological evidence that points to when Neanderthal and Homo sapiens cultures overlapped in parts of Europe and Asia.

What’s still not clear is whether that period of contact lasted the full 5,000 to 7,000 years, or if, as Johannes Krause (also of the Max Planck Institute) suggests, it was only a few centuries—1,500 years at the most—that fell somewhere within that range of dates.

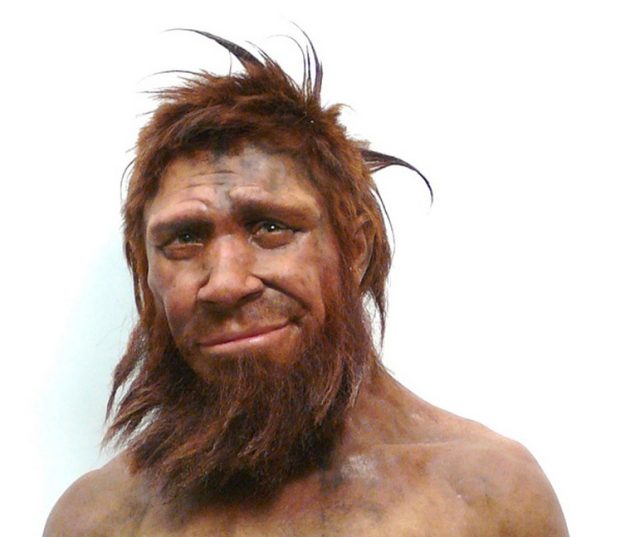

Artist’s depiction of a Neanderthal.

Natural selection worked fast on our borrowed Neanderthal DNA

Once those first Homo sapiens in Eurasia had acquired their souvenir Neanderthal genes (forget stealing a partner’s hoodie; just take some useful segments of their genome), natural selection got to work on them very quickly, discarding some and passing along others, so that by about 100 generations after the “event,” the pattern of Neanderthal DNA segments in people’s genomes looked a lot like it does today.

Iasi and his colleagues looked through their catalog of genomes for sections that contained more (or less) Neanderthal ancestry than you’d expect to find by random chance—a pattern that suggests that natural selection has been at work on those segments. Some of the segments that tended to include more Neanderthal gene variants included areas related to skin pigmentation, the immune response, and metabolism. And that makes perfect sense, according to Iasi.

“Neanderthals had lived in Europe, or outside of Africa, for thousands of years already, so they were probably adapted to their environment, climate, and pathogens,” said Iasi during the press conference. Homo sapiens were facing selective pressure to adapt to the same challenges, so genes that gave them an advantage would have been more likely to get passed along, while unhelpful ones would have been quick to get weeded out.

The most interesting questions remain unanswered

The Neanderthal DNA that many people carry today, the researchers argue, is a legacy from just 100 or 200 Neanderthals.

“The effective population size of modern humans outside Africa was about 5,000,” said Krause in the press conference. “And we have a ratio of about 50 to 1 in terms of admixture [meaning that Neanderthal segments account for about 2 percent of modern genomes in people who aren’t of African ancestry], so we have to say it was about 100 to maybe 200 Neanderthals roughly that mixed into the population.” Assuming Krause is right about that and about how long the two species stayed in contact, a Homo sapiens/Neanderthal pairing would have happened every few years.

So we know that Neanderthals and members of our species lived in close proximity and occasionally produced children for at least several centuries, but no artifacts, bones, or ancient DNA have yet revealed much of what that time, or that relationship, was actually like for either group of people.

The snippets of Neanderthal ancestry left in many modern genomes, and those of people who lived tens of thousands of years ago, don’t offer any hints about whether that handful of Neanderthal ancestors were mostly male or mostly female, which is something that could shed light on the cultural rules around such pairings. And nothing archaeologists have unearthed so far can tell us whether those pairings were consensual, whether they were long-term relationships or hasty flings, or whether they involved social relationships recognized by one (or both) groups. We may never have answers to those questions.

And where did it all happen? Archaeologists haven’t yet found a cave wall inscribed with “Og heart Grag,” but based on the timing, Neanderthals and Homo sapiens probably met and lived alongside each other for at least a few centuries, somewhere in “the Near East,” which includes parts of North Africa, the Levant, what’s now Turkey, and what was once Mesopotamia. That’s one of the key routes that people would have followed as they migrated from Africa into Europe and Asia, and the timing lines up with when we know that both Homo sapiens and Neanderthals were in the area.

“This [same] genetic admixture also appears in East Asia and Australia and the Americas and Europe,” said Krause. “If it would have happened in Europe or somewhere else, then the distribution would probably look different than what we see.”

Science, 2023 DOI: 10.1126/science.adq3010;

Nature, 2023 DOI: 10.1038/s41586-024-08420-x;

Studies pin down exactly when humans and Neanderthals swapped DNA Read More »