When Amazon badly needed a ride, Europe’s Ariane 6 rocket delivered

The Ariane 64 flew with an extended payload shroud to fit all 32 Amazon Leo satellites. Combined, the payload totaled around 20 metric tons, or about 44,000 pounds, according to Arianespace. This is close to maxing out the Ariane 64’s lift capability.

Amazon has booked more than 100 missions across four launch providers to populate the company’s planned fleet of more than 3,200 satellites. With Thursday’s launch, Amazon has launched 214 production satellites on eight missions with United Launch Alliance, SpaceX, and now Arianespace.

The Amazon Leo constellation is a competitor with SpaceX’s Starlink Internet network. SpaceX now has more than 9,000 satellites in orbit beaming broadband to more than 9 million subscribers, and all have launched on the company’s own Falcon 9 rockets. Amazon, meanwhile, initially bypassed SpaceX when selecting which companies would launch satellites for the Amazon Leo program, formerly known as Project Kuiper.

Amazon booked the last nine launches on ULA’s soon-to-retire Atlas V, five of which have now flown, and reserved the rest of its launches in 2022 on rockets that had never launched before: 38 flights on ULA’s new Vulcan rocket, 24 launches on Blue Origin’s New Glenn, and 18 on Europe’s Ariane 6.

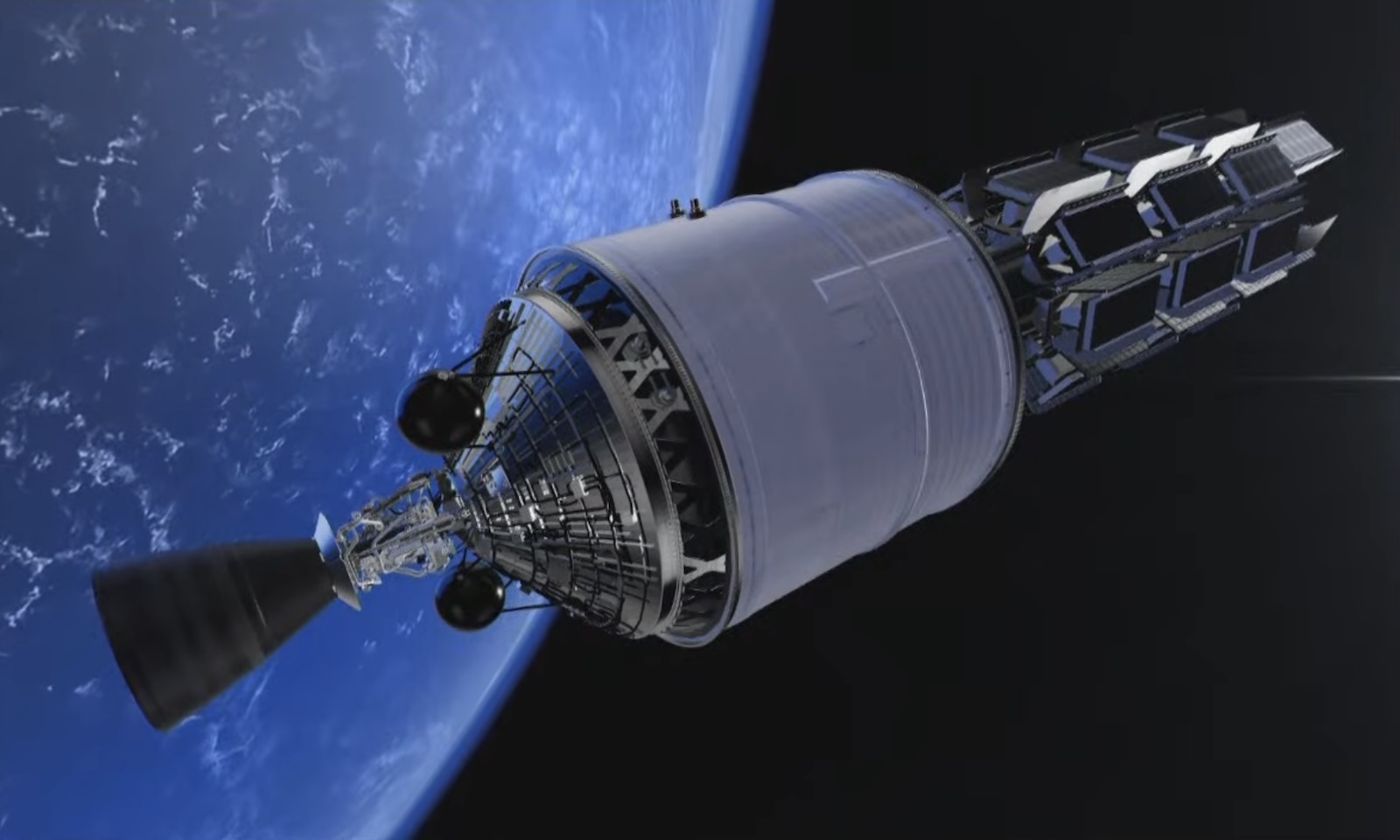

An artist’s illustration of the Ariane 6’s upper stage in orbit with a stack of Amazon Leo satellites awaiting deployment. Credit: Arianespace

Meanwhile, in Florida

All three new rockets suffered delays but are now in service. The Ariane 6 has enjoyed the fastest ramp-up in launch cadence, with six flights under its belt after Thursday’s mission from French Guiana. ULA’s Vulcan rocket has flown four times, and Amazon says its first batch of satellites to fly on Vulcan is now complete. But a malfunction with one of the Vulcan launcher’s solid rocket boosters on a military launch from Florida early Thursday—the second such anomaly in three flights—raises questions about when Amazon will get its first ride on Vulcan.

Blue Origin, owned by Amazon founder Jeff Bezos, is gearing up for the third flight of its heavy-lift New Glenn rocket from Florida as soon as next month. Amazon and Blue Origin have not announced when the first group of Amazon Leo satellites will launch on New Glenn.

When Amazon badly needed a ride, Europe’s Ariane 6 rocket delivered Read More »