NASA has a new problem to fix before the next Artemis II countdown test

John Honeycutt, chair of NASA’s Artemis II mission management team, said the decision to relax the safety limit between Artemis I and Artemis II was grounded in test data.

“The SLS program, they came up with a test campaign that actually looked at that cavity, the characteristics of the cavity, the purge in the cavity … and they introduced hydrogen to see when you could actually get it to ignite, and at 16 percent, you could not,” said Honeycutt, who served as NASA’s SLS program manager before moving to his new job.

Hydrogen is explosive in high concentrations when mixed with air. This is what makes hydrogen a formidable rocket fuel. But it is also notoriously difficult to contain. Molecular hydrogen is the smallest molecule, meaning it can readily escape through leak paths, and poses a materials challenge for seals because liquified hydrogen is chilled to minus 423 degrees Fahrenheit (minus 253 degrees Celsius).

So, it turns out NASA used the three-year interim between Artemis I and Artemis II to get comfortable with a more significant hydrogen leak, instead of fixing the leaks themselves. Isaacman said that will change before Artemis III, which likewise is probably at least three years away.

“I will say near-conclusively for Artemis III, we will cryoproof the vehicle before it gets to the pad, and the propellant loading interfaces we are troubleshooting will be redesigned,” Isaacman wrote.

Isaacman took over as NASA’s administrator in December, and has criticized the SLS program’s high cost—estimated by NASA’s inspector general at more than $2 billion per rocket—along with the launch vehicle’s torpid flight rate.

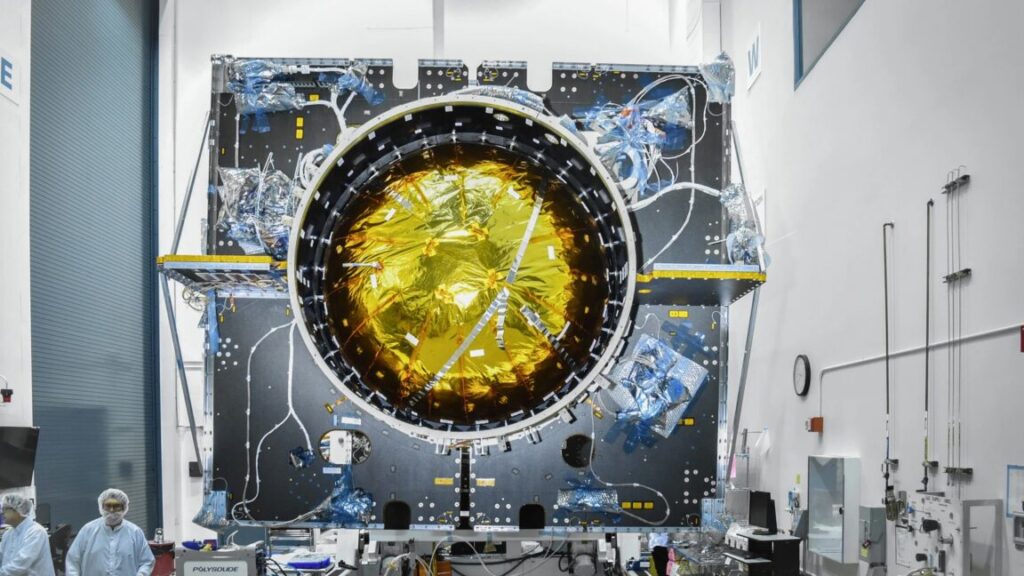

NASA’s expenditures for the rocket’s ground systems at Kennedy Space Center are similarly enormous. NASA spent nearly $900 million on Artemis ground support infrastructure in 2024 alone. Much of the money went toward constructing a new launch platform for an upgraded version of the Space Launch System that may never fly.

All of this makes each SLS rocket a golden egg, a bespoke specimen that must be treated with care because it is too expensive to replace. NASA and Boeing, the prime contractor for the SLS core stage, never built a full-size test model of the core stage. There’s currently no way to completely test the cryogenic interplay between the core stage and ground equipment until the fully assembled rocket is on the launch pad.

Existing law requires NASA continue flying the SLS rocket through the Artemis V mission. Isaacman wrote that the Artemis architecture “will continue to evolve as we learn more and as industry capabilities mature.” In other words, NASA will incorporate newer, cheaper, reusable rockets into the Artemis program.

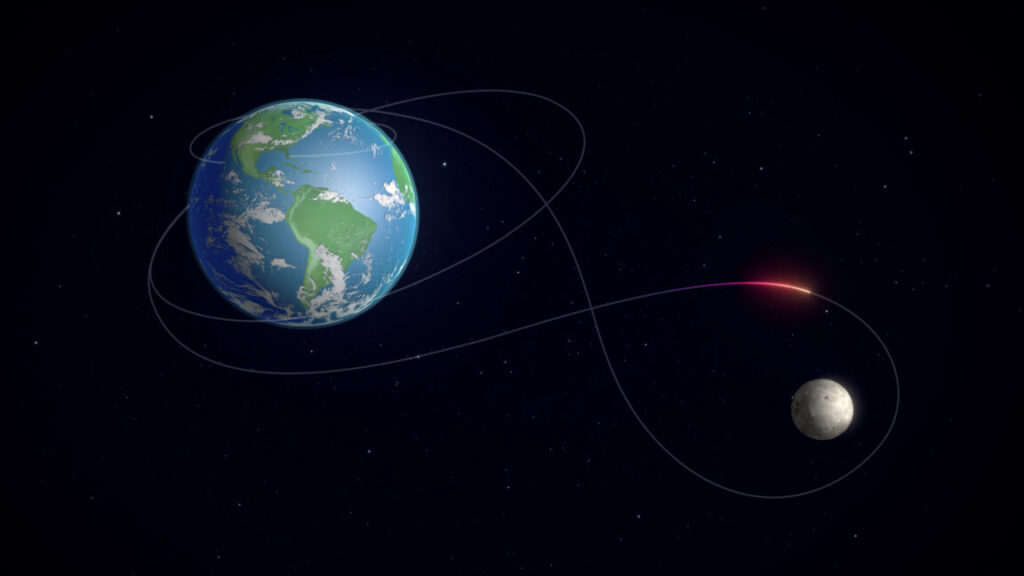

The next series of launch opportunities for the Artemis II mission begin March 3. If the mission doesn’t lift off in March, NASA will need to roll the rocket back to the Vehicle Assembly Building to refresh its flight termination system. There are more launch dates available in April and May.

“There is still a great deal of work ahead to prepare for this historic mission,” Isaacman wrote. “We will not launch unless we are ready and the safety of our astronauts will remain the highest priority. We will keep everyone informed as NASA prepares to return to the Moon.”

NASA has a new problem to fix before the next Artemis II countdown test Read More »