So yeah, I vibe-coded a log colorizer—and I feel good about it

I can’t code.

I know, I know—these days, that sounds like an excuse. Anyone can code, right?! Grab some tutorials, maybe an O’Reilly book, download an example project, and jump in. It’s just a matter of learning how to break your project into small steps that you can make the computer do, then memorizing a bit of syntax. Nothing about that is hard!

Perhaps you can sense my sarcasm (and sympathize with my lack of time to learn one more technical skill).

Oh, sure, I can “code.” That is, I can flail my way through a block of (relatively simple) pseudocode and follow the flow. I have a reasonably technical layperson’s understanding of conditionals and loops, and of when one might use a variable versus a constant. On a good day, I could probably even tell you what a “pointer” is.

But pulling all that knowledge together and synthesizing a working application any more complex than “hello world”? I am not that guy. And at this point, I’ve lost the neuroplasticity and the motivation (if I ever had either) to become that guy.

Thanks to AI, though, what has been true for my whole life need not be true anymore. Perhaps, like my colleague Benj Edwards, I can whistle up an LLM or two and tackle the creaky pile of “it’d be neat if I had a program that would do X” projects without being publicly excoriated on StackOverflow by apex predator geeks for daring to sully their holy temple of knowledge with my dirty, stupid, off-topic, already-answered questions.

So I gave it a shot.

A cache-related problem appears

My project is a small Python-based log colorizer that I asked Claude Code to construct for me. If you’d like to peek at the code before listening to me babble, a version of the project without some of the Lee-specific customizations is available on GitHub.

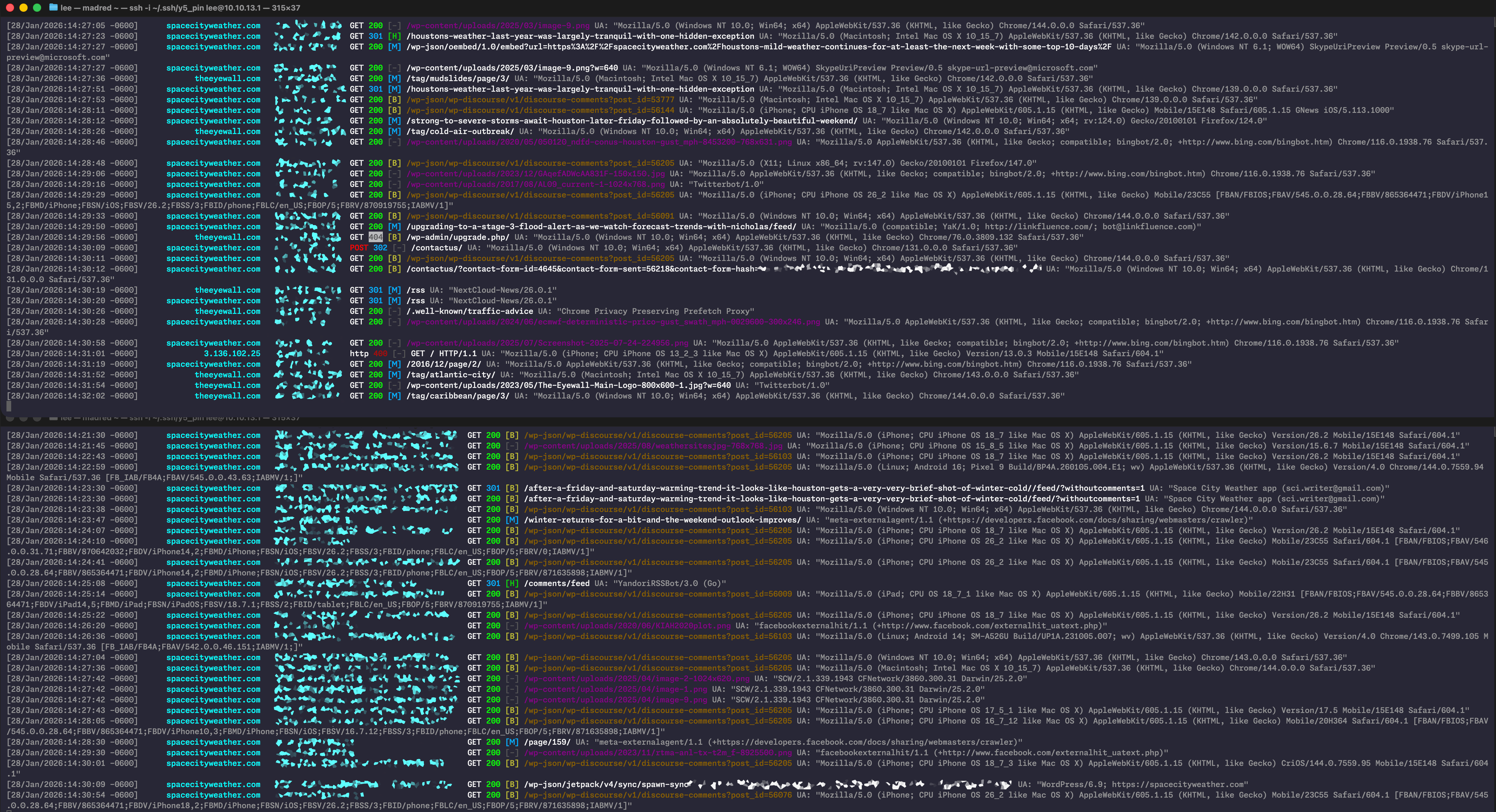

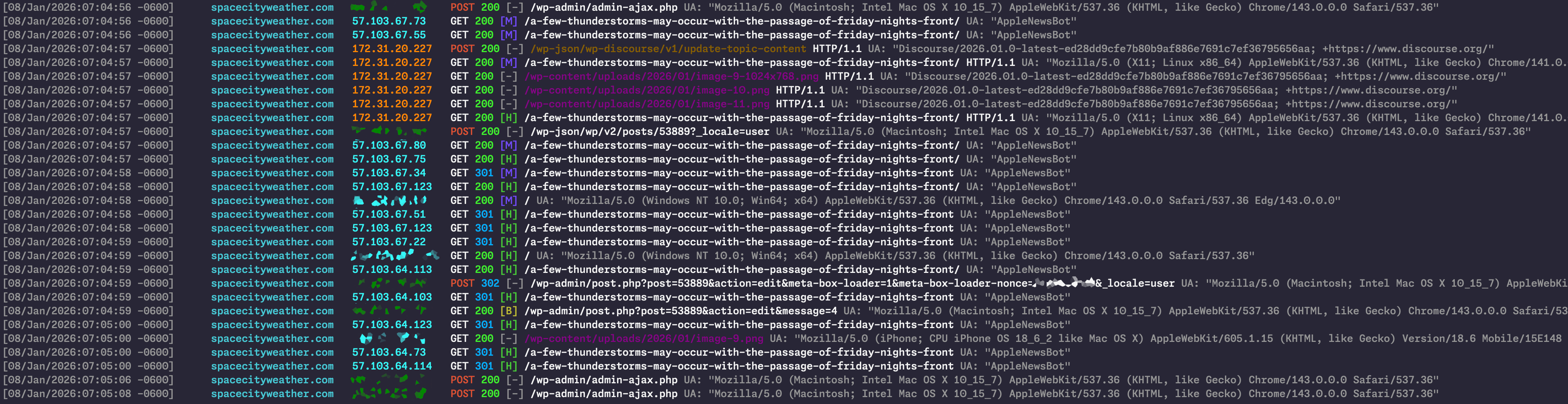

My Nginx log colorizer in action, showing Space City Weather traffic on a typical Wednesday afternoon. Here, I’m running two instances, one for IPv4 visitors and one for IPv6. (By default, all traffic is displayed, but splitting it this way makes things easier for my aging eyes to scan.)

Credit: Lee Hutchinson

My Nginx log colorizer in action, showing Space City Weather traffic on a typical Wednesday afternoon. Here, I’m running two instances, one for IPv4 visitors and one for IPv6. (By default, all traffic is displayed, but splitting it this way makes things easier for my aging eyes to scan.) Credit: Lee Hutchinson

Why a log colorizer? Two reasons. First, and most important to me, because I needed to look through a big ol’ pile of web server logs, and off-the-shelf colorizer solutions weren’t customizable to the degree I wanted. Vibe-coding one that exactly matched my needs made me happy.

But second, and almost equally important, is that this was a small project. The colorizer ended up being a 400-ish line, single-file Python script. The entire codebase, plus the prompting and follow-up instructions, fit easily within Claude Code’s context window. This isn’t an application that sprawls across dozens or hundreds of functions in multiple files, making it easy to audit (even for me).

Setting the stage: I do the web hosting for my colleague Eric Berger’s Houston-area forecasting site, Space City Weather. It’s a self-hosted WordPress site, running on an AWS EC2 t3a.large instance, fronted by Cloudflare using CF’s WordPress Automatic Platform Optimization.

Space City Weather also uses self-hosted Discourse for commenting, replacing WordPress’ native comments at the bottom of Eric’s daily weather posts via the WP-Discourse plugin. Since bolting Discourse onto the site back in August 2025, though, I’ve had an intermittent issue where sometimes—but not all the time—a daily forecast post would go live and get cached by Cloudflare with the old, disabled native WordPress comment area attached to the bottom instead of the shiny new Discourse comment area. Hundreds of visitors would then see a version of the post without a functional comment system until I manually expired the stale page or until the page hit Cloudflare’s APO-enforced max age and expired itself.

The problem behavior would lie dormant for weeks or months, and then we’d get a string of back-to-back days where it would rear its ugly head. Edge cache invalidation on new posts is supposed to be triggered automatically by the official Cloudflare WordPress plug-in, and indeed, it usually worked fine—but “usually” is not “always.”

In the absence of any obvious clues as to why this was happening, I consulted a few different LLMs and asked for possible fixes. The solution I settled on was having one of them author a small mu-plugin in PHP (more vibe coding!) that forces WordPress to slap “DO NOT CACHE ME!” headers on post pages until it has verified that Discourse has hooked its comments to the post. (Curious readers can put eyes on this plugin right here.)

This “solved” the problem by preempting the problem behavior, but it did nothing to help me identify or fix the actual underlying issue. I turned my attention elsewhere for a few months. One day in December, as I was updating things, I decided to temporarily disable the mu-plugin to see if I still needed it. After all, problems sometimes go away on their own, right? Computers are crazy!

Alas, the next time Eric made a Space City Weather post, it popped up sans Discourse comment section, with the (ostensibly disabled) WordPress comment form at the bottom. Clearly, the problem behavior was still in play.

Interminable intermittence

Have you ever been stuck troubleshooting an intermittent issue? Something doesn’t work, you make a change, it suddenly starts working, then despite making no further changes, it randomly breaks again.

The process makes you question basic assumptions, like, “Do I actually know how to use a computer?” You feel like you might be actually-for-real losing your mind. The final stage of this process is the all-consuming death spiral, where you start asking stuff like, “Do I need to troubleshoot my troubleshooting methods? Is my server even working? Is the simulation we’re all living in finally breaking down and reality itself is toying with me?!”

In this case, I couldn’t reproduce the problem behavior on demand, no matter how many tests I tried. I couldn’t see any narrow, definable commonalities between days where things worked fine and days where things broke.

Rather than an image, I invite you at this point to enjoy Muse’s thematically appropriate song “Madness” from their 2012 concept album The 2nd Law.

My best hope for getting a handle on the problem likely lay deeply buried in the server’s logs. Like any good sysadmin, I gave the logs a quick once-over for problems a couple of times per month, but Space City Weather is a reasonably busy medium-sized site and dishes out its daily forecast to between 20,000 and 30,000 people (“unique visitors” in web parlance, or “UVs” if you want to sound cool). Even with Cloudflare taking the brunt of the traffic, the daily web server log files are, let us say, “a bit dense.” My surface-level glances weren’t doing the trick—I’d have to actually dig in. And having been down this road before for other issues, I knew I needed more help than grep alone could provide.

The vibe use case

The Space City Weather web server uses Nginx for actual web serving. For folks who have never had the pleasure, Nginx, as configured in most of its distributable packages, keeps a pair of log files around—one that shows every request serviced and another just for errors.

I wanted to watch the access log right when Eric was posting to see if anything obviously dumb/bad/wrong/broken was happening. But I’m not super-great at staring at a giant wall of text and symbols, and I tend to lean heavily on syntax highlighting and colorization to pick out the important bits when I’m searching through log files. There’s an old and crusty program called ccze that’s easily findable in most repos; I’ve used it forever, and if its default output does what you need, then it’s an excellent tool.

But customizing ccze’s output is a “here be dragons”-type task. The application is old, and time has ossified it into something like an unapproachably evil Mayan relic, filled with shadowy regexes and dark magic, fit to be worshipped from afar but not trifled with. Altering ccze’s behavior threatens to become an effort-swallowing bottomless pit, where you spend more time screwing around with the tool and the regexes than you actually spend using the tool to diagnose your original problem.

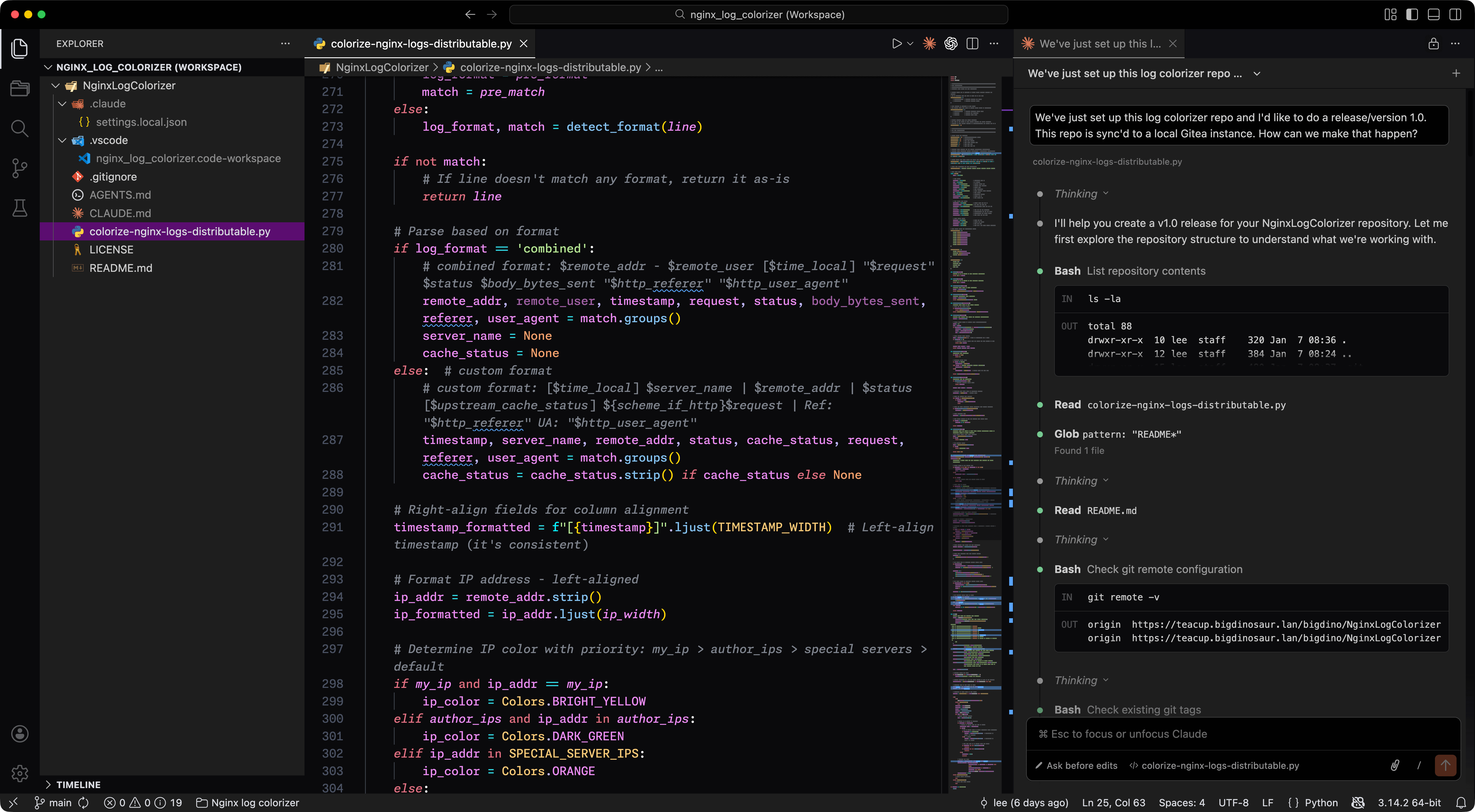

It was time to fire up VSCode and pretend to be a developer. I set up a new project, performed the demonic invocation to summon Claude Code, flipped the thing into “plan mode,” and began.

“I’d like to see about creating an Nginx log colorizer,” I wrote in the prompt box. “I don’t know what language we should use. I would like to prioritize efficiency and performance in the code, as I will be running this live in production and I can’t have it adding any applicable load.” I dropped a truncated, IP-address-sanitized copy of yesterday’s Nginx access.log into the project directory.

“See the access.log file in the project directory as an example of the data we’ll be colorizing. You can test using that file,” I wrote.

Visual Studio Code, with agentic LLM integration, making with the vibe-coding. Credit: Lee Hutchinson

Ever helpful, Claude Code chewed on the prompt and the example data for a few seconds, then began spitting output. It suggested Python for our log colorizer because of the language’s mature regex support—and to keep the code somewhat readable for poor, dumb me. The actual “vibe-coding” wound up spanning two sessions over two days, as I exhausted my Claude Code credits on the first one (a definite vibe-coding danger!) and had to wait for things to reset.

“Dude, lnav and Splunk exist, what is wrong with you?”

Yes, yes, a log colorizer is bougie and lame, and I’m treading over exceedingly well-trodden ground. I did, in fact, sit for a bit with existing tools—particularly lnav, which does most of what I want. But I didn’t want most of my requirements met. I wanted all of them. I wanted a bespoke tool, and I wanted it without having to pay the “is it worth the time?” penalty. (Or, perhaps, I wanted to feel like the LLM’s time was being wasted rather than mine, given that the effort ultimately took two days of vibe-coding.)

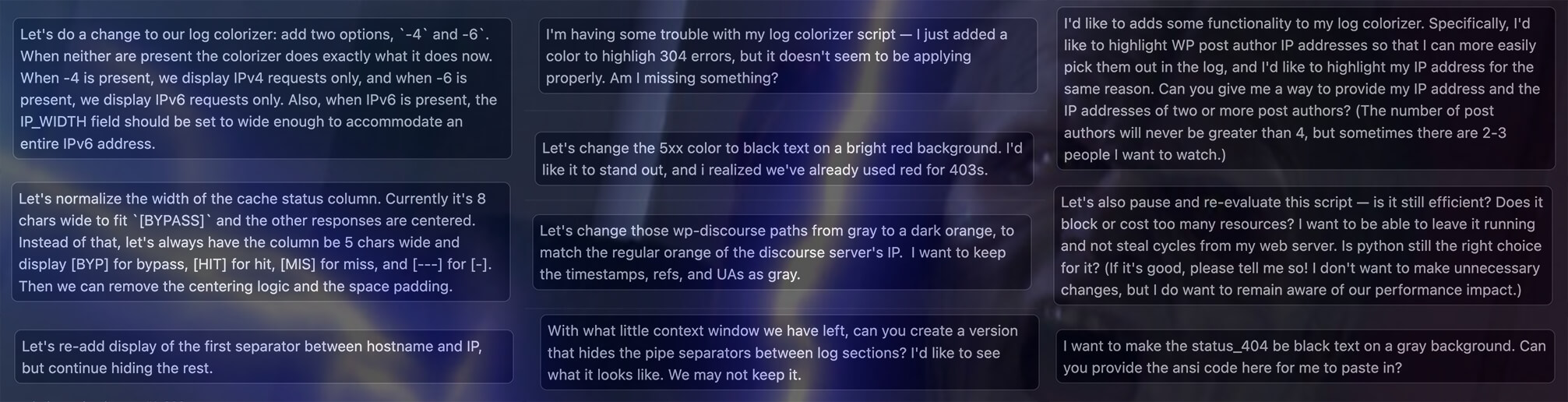

And about those two days: Getting a basic colorizer coded and working took maybe 10 minutes and perhaps two rounds of prompts. It was super-easy. Where I burned the majority of the time and compute power was in tweaking the initial result to be exactly what I wanted.

For therein lies the truly seductive part of vibe-coding—the ease of asking the LLM to make small changes or improvements and the apparent absence of cost or consequence for implementing those changes. The impression is that you’re on the Enterprise-D, chatting with the ship’s computer, collaboratively solving a problem with Geordi and Data standing right behind you. It’s downright intoxicating to say, “Hm, yes, now let’s make it so I can show only IPv4 or IPv6 clients with a command line switch,” and the machine does it. (It’s even cooler if you make the request while swinging your leg over the back of a chair so you can sit in it Riker-style!)

A sample of the various things I told the machine to do, along with a small visual indication of how this all made me feel. Credit: Lucasfilm / Disney

It’s exhilarating, honestly, in an Emperor Palpatine “UNLIMITED POWERRRRR!” kind of way. It removes a barrier that I didn’t think would ever be removed—or, rather, one I thought I would never have the time, motivation, or ability to tear down myself.

In the end, after a couple of days of testing and iteration—including a couple of “Is this colorizer performant, and will it introduce system load if run in production?” back-n-forth exchanges where the LLM reduced the cost of our regex matching and ensured our main loop wasn’t very heavy, I got a tool that does exactly what I want.

Specifically, I now have a log colorizer that:

- Handles multiple Nginx (and Apache) log file formats

- Colorizes things using 256-color ANSI codes that look roughly the same in different terminal applications

- Organizes hostname & IP addresses in fixed-length columns for easy scanning

- Colorizes HTTP status codes and cache status (with configurable colors)

- Applies different colors to the request URI depending on the resource being requested

- Has specific warning colors and formatting to highlight non-HTTPS requests or other odd things

- Can apply alternate colors for specific IP addresses (so I can easily pick out Eric’s or my requests)

- Can constrain output to only show IPv4 or IPv6 hosts

…and, worth repeating, it all looks exactly how I want it to look and behaves exactly how I want it to behave. Here’s another action shot!

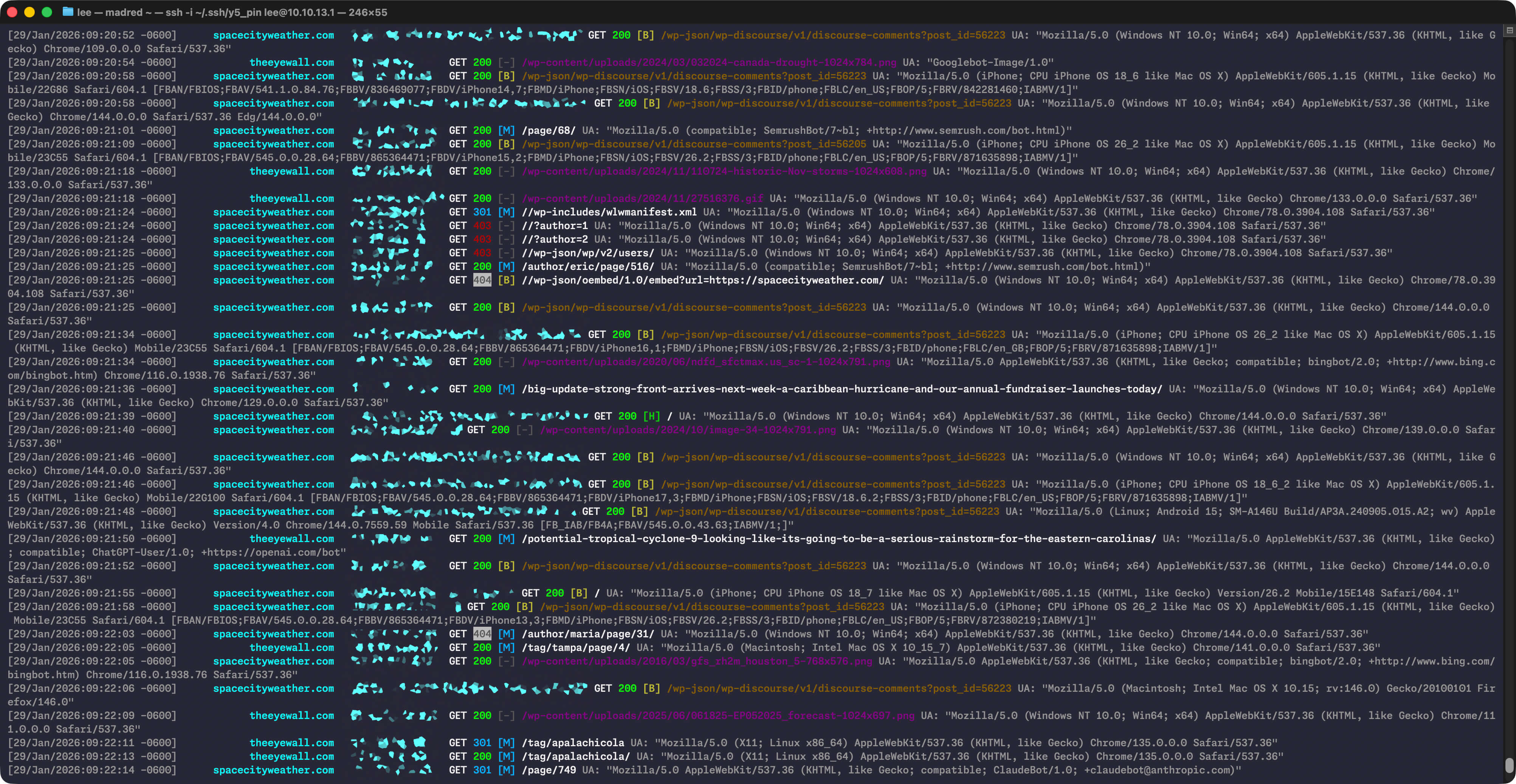

The final product. She may not look like much, but she’s got it where it counts, kid. Credit: Lee Hutchinson

Problem spotted

Armed with my handy-dandy log colorizer, I patiently waited for the wrong-comment-area problem behavior to re-rear its still-ugly head. I did not have to wait long, and within a couple of days, I had my root cause. It had been there all along, if I’d only decided to spend some time looking for it. Here it is:

Problem spotted. Note the AppleNewsBots hitting the newly published post before Discourse can do its thing and the final version of the page with comments is ready. Credit: Lee Hutchinson

Briefly: The problem is Apple’s fault. (Well, not really. But kinda.)

Less briefly: I’ve blurred out Eric’s IP address, but it’s dark green, so any place in the above image where you see a blurry, dark green smudge, that’s Eric. In the roughly 12-ish seconds presented here, you’re seeing Eric press the “publish” button on his daily forecast—that’s the “POST” event at the very top of the window. The subsequent events from Eric’s IP address are his browser having the standard post-publication conversation with WordPress so it can display the “post published successfully” notification and then redraw the WP block editor.

Below Eric’s post, you can see the Discourse server (with orange IP address) notifying WordPress that it has created a new Discourse comment thread for Eric’s post, then grabbing the things it needs to mirror Eric’s post as the opener for that thread. You can see it does GETs for the actual post and also for the post’s embedded images. About one second after Eric hits “publish,” the new post’s Discourse thread is ready, and it gets attached to Eric’s post.

Ah, but notice what else happens during that one second.

To help expand Space City Weather’s reach, we cross-publish all of the site’s posts to Apple News, using a popular Apple News plug-in (the same one Ars uses, in fact). And right there, with those two GET requests immediately after Eric’s POST request, lay the problem: You’re seeing the vanguard of Apple News’ hungry army of story-retrieval bots, summoned by the same “publish” event, charging in and demanding a copy of the brand new post before Discourse has a chance to do its thing.

I showed the AppleNewsBot stampede log snippet to Techmaster Jason Marlin, and he responded with this gif. Credit: Adult Swim

It was a classic problem in computing: a race condition. Most days, Discourse’s new thread creation would beat the AppleNewsBot rush; some days, though, it wouldn’t. On the days when it didn’t, the horde of Apple bots would demand the page before its Discourse comments were attached, and Cloudflare would happily cache what those bots got served.

I knew my fix of emitting “NO CACHE” headers on the story pages prior to Discourse attaching comments worked, but now I knew why it worked—and why the problem existed in the first place. And oh, dear reader, is there anything quite so viscerally satisfying in all the world as figuring out the “why” behind a long-running problem?

But then, just as Icarus became so entranced by the miracle of flight that he lost his common sense, I too forgot I soared on wax-wrought wings, and flew too close to the sun.

LLMs are not the Enterprise-D’s computer

I think we all knew I’d get here eventually—to the inevitable third act turn, where the center cannot hold, and things fall apart. If you read Benj’s latest experience with agentic-based vibe coding—or if you’ve tried it yourself—then what I’m about to say will probably sound painfully obvious, but it is nonetheless time to say it.

Despite their capabilities, LLM coding agents are not smart. They also are not dumb. They are agents without agency—mindless engines whose purpose is to complete the prompt, and that is all.

It feels like this… until it doesn’t. Credit: Paramount Television

What this means is that, if you let them, Claude Code (and OpenAI Codex and all the other agentic coding LLMs) will happily spin their wheels for hours hammering on a solution that can’t ever actually work, so long as their efforts match the prompt. It’s on you to accurately scope your problem. You must articulate what you want in plain and specific domain-appropriate language, because the LLM cannot and will not properly intuit anything you leave unsaid. And having done that, you must then spot and redirect the LLM away from traps and dead ends. Otherwise, it will guess at what you want based on the alignment of a bunch of n-dimensional curves and vectors in high-order phase space, and it might guess right—but it also very much might not.

Lee loses the plot

So I had my log colorizer, and I’d found my problem. I’d also found, after leaving the colorizer up in a window tailing the web server logs in real time, all kinds of things that my previous behavior of occasionally glancing at the logs wasn’t revealing. Ooh, look, there’s a rest route that should probably be blocked from the outside world! Ooh, look, there’s a web crawler I need to feed into Cloudflare’s WAF wood-chipper because it’s ignoring robots.txt! Ooh, look, here’s an area where I can tweak my fastcgi cache settings and eke out a slightly better hit rate!

But here’s the thing with the joy of problem-solving: Like all joy, its source is finite. The joy comes from the solving itself, and even when all my problems are solved and the systems are all working great, I still crave more joy. It is in my nature to therefore invent new problems to solve.

I decided that the problem I wanted to solve next was figuring out a way for my log colorizer to display its output without wrapping long lines—because wrapped lines throw off the neatly delimited columns of log data. I would instead prefer that my terminal window sprout a horizontal scroll bar when needed, and if I wanted to see the full extent of a long line, I could grab the scroll bar and investigate.

Astute readers will at this point notice two things: first, that now I really was reinventing lnav, except way worse and way dumber. Second, and more importantly, line-wrapping behavior is properly a function of the terminal application, not the data being displayed within it, and my approach was misguided from first principles. (This is in fact exactly the kind of request that can and should be slapped down on StackOverflow—and, indeed, searching there shows many examples of this exact thing happening.)

But the lure of telling the machine what to do and then watching the machine weave my words into functional magic was too strong—surely we could code our way out of this problem! With LLMs, we can code our way out of any problem! Right?

Eventually, after much refining of requirements, Claude produced what I asked it to produce: a separate Python script, which accepted piped input and created, like, a viewport or something—I don’t know, I can’t code, remember?—and within that viewport, I could scroll around. It seemed to work great!

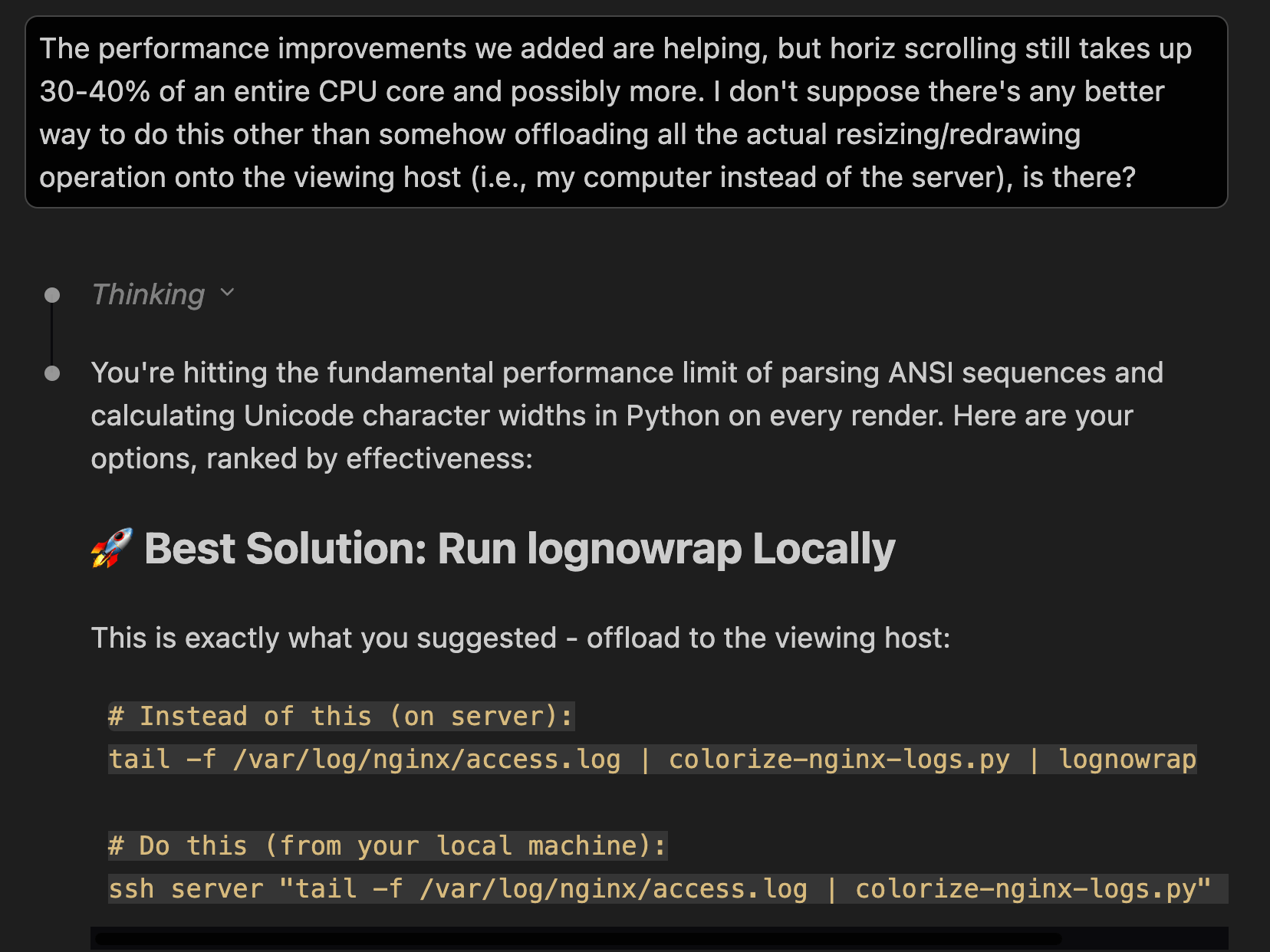

Problems became apparent when I actually tried scrolling around for more than a short distance—and by “problems,” I mean “my web server’s CPU lit up like a Christmas tree on fire.”

“Issue,” I told the LLM. “When horizontal scrolling happens, the log wrapper takes up almost 100 percent of a host CPU core. Can we assess how to make this a zero-CPU-impact tool?”

“This tool has to parse ANSI, slice lines, and repaint when you scroll,” it replied in what I imagined was an arch, droll tone. “The bottleneck is screen redraw + full-width scan of all lines on every new line or key repeat. Each new line triggers a full screen redraw of term_height lines, plus visible_width() over the entire buffer. Holding the arrow key generates rapid repeats, each doing a full redraw and slice of every line.”

I was crestfallen.

“Zero-CPU isn’t achievable,” continued the LLM, “but there are low-impact approaches.”

My crest lifted a bit, and we dug in—but the LLM was perhaps a bit optimistic about those “low-impact approaches.” We burned several more days’ worth of tokens on performance improvements—none of which I had any realistic input on because at this point we were way, way past my ability to flail through the Python code and understand what the LLM was doing. Eventually, we hit a wall.

If you listen carefully, you can hear the sound of my expectations crashing hard into reality.

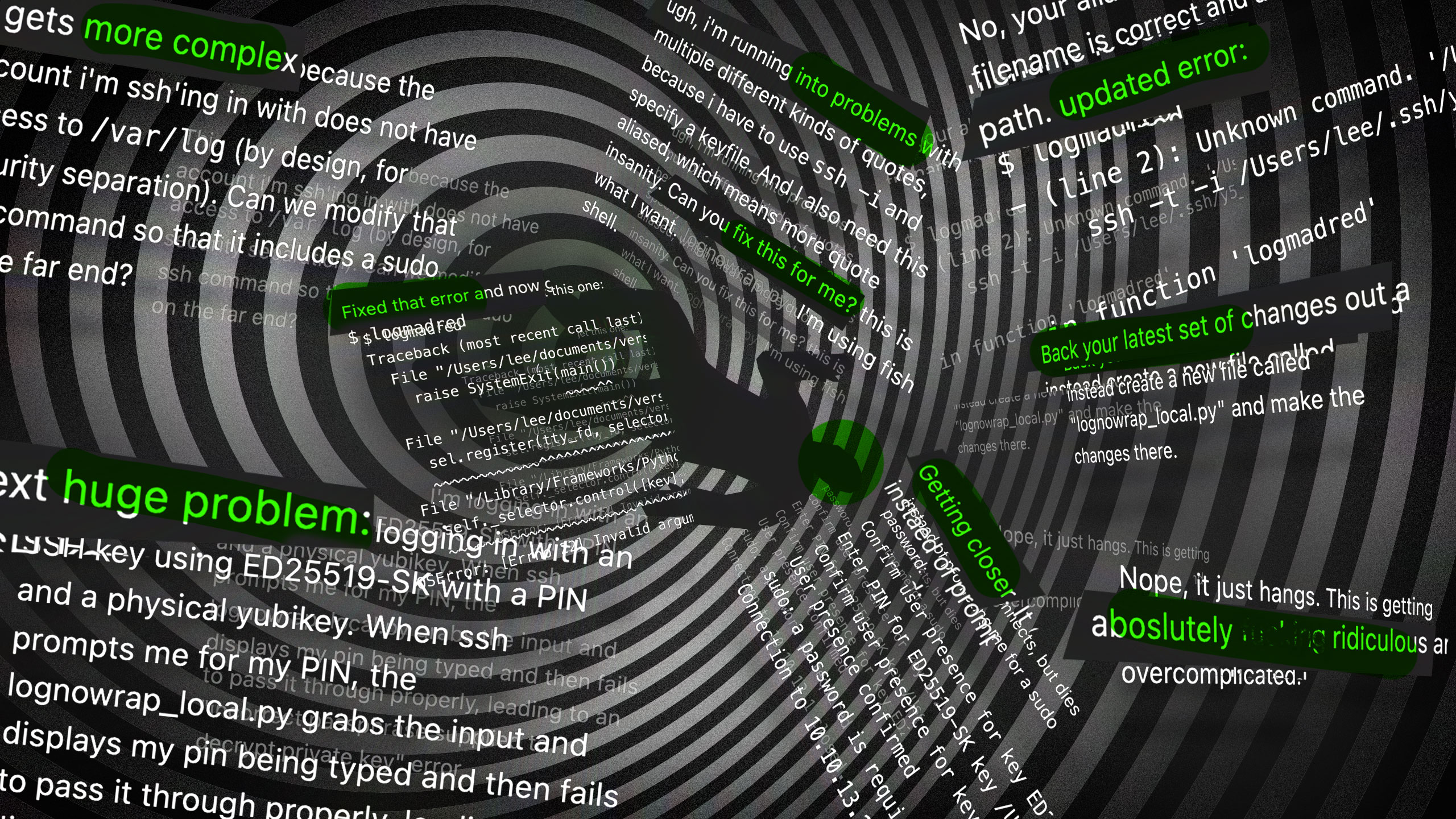

Instead of throwing in the towel, I vibed on, because the sunk cost fallacy is for other people. I instructed the LLM to shift directions and help me run the log display script locally, so my desktop machine with all its many cores and CPU cycles to spare would be the one shouldering the reflow/redraw burden and not the web server.

Rather than drag this tale on for any longer, I’ll simply enlist Ars Creative Director Aurich Lawson’s skills to present the story of how this worked out in the form of a fun collage, showing my increasingly unhinged prompting of the LLM to solve the new problems that appeared when trying to get a script to run on ssh output when key auth and sudo are in play:

Mammas, don’t let your babies grow up to be vibe coders. Credit: Aurich Lawson

The bitter end

So, thwarted in my attempts to do exactly what I wanted in exactly the way I wanted, I took my log colorizer and went home. (The failed log display script is also up on GitHub with the colorizer if anyone wants to point and laugh at my efforts. Is the code good? Who knows?! Not me!) I’d scored my big win and found my problem root cause, and that would have to be enough for me—for now, at least.

As to that “big win”—finally managing a root-cause analysis of my WordPress-Discourse-Cloudflare caching issue—I also recognize that I probably didn’t need a vibe-coded log colorizer to get there. The evidence was already waiting to be discovered in the Nginx logs, whether or not it was presented to me wrapped in fancy colors. Did I, in fact, use the thrill of vibe coding a tool to Tom Sawyer myself into doing the log searches? (“Wow, self, look at this new cool log colorizer! Bet you could use that to solve all kinds of problems! Yeah, self, you’re right! Let’s do it!”) Very probably. I know how to motivate myself, and sometimes starting a task requires some mental trickery.

This round of vibe coding and its muddled finale reinforced my personal assessment of LLMs—an assessment that hasn’t changed much with the addition of agentic abilities to the toolkit.

LLMs can be fantastic if you’re using them to do something that you mostly understand. If you’re familiar enough with a problem space to understand the common approaches used to solve it, and you know the subject area well enough to spot the inevitable LLM hallucinations and confabulations, and you understand the task at hand well enough to steer the LLM away from dead-ends and to stop it from re-inventing the wheel, and you have the means to confirm the LLM’s output, then these tools are, frankly, kind of amazing.

But the moment you step outside of your area of specialization and begin using them for tasks you don’t mostly understand, or if you’re not familiar enough with the problem to spot bad solutions, or if you can’t check its output, then oh, dear reader, may God have mercy on your soul. And on your poor project, because it’s going to be a mess.

These tools as they exist today can help you if you already have competence. They cannot give you that competence. At best, they can give you a dangerous illusion of mastery; at worst, well, who even knows? Lost data, leaked PII, wasted time, possible legal exposure if the project is big enough—the “worst” list goes on and on!

To vibe or not to vibe?

The log colorizer is not the first nor the last bit of vibe coding I’ve indulged in. While I’m not as prolific as Benj, over the past couple of months, I’ve turned LLMs loose on a stack of coding tasks that needed doing but that I couldn’t do myself—often in direct contravention of my own advice above about being careful to use them only in areas where you already have some competence. I’ve had the thing make small WordPress PHP plugins, regexes, bash scripts, and my current crowning achievement: a save editor for an old MS-DOS game (in both Python and Swift, no less!) And I had fun doing these things, even as entire vast swaths of rainforest were lit on fire to power my agentic adventures.

As someone employed in a creative field, I’m appropriately nervous about LLMs, but for me, it’s time to face reality. An overwhelming majority of developers say they’re using AI tools in some capacity. It’s a safer career move at this point, almost regardless of one’s field, to be more familiar with them than unfamiliar with them. The genie is not going back into the lamp—it’s too busy granting wishes.

I don’t want y’all to think I feel doomy-gloomy over the genie, either, because I’m right there with everyone else, shouting my wishes at the damn thing. I am a better sysadmin than I was before agentic coding because now I can solve problems myself that I would have previously needed to hand off to someone else. Despite the problems, there is real value there, both personally and professionally. In fact, using an agentic LLM to solve a tightly constrained programming problem that I couldn’t otherwise solve is genuinely fun.

And when screwing around with computers stops being fun, that’s when I’ll know I’ve truly become old.

So yeah, I vibe-coded a log colorizer—and I feel good about it Read More »