Lawsuit: EPA revoking greenhouse gas finding risks “thousands of avoidable deaths”

EPA sued for abandoning its mission to protect public health.

In a lawsuit filed Wednesday, the Environmental Protection Agency was accused of abandoning its mission to protect public health after repealing an “endangerment finding” that has served as the basis for federal climate change regulations for 17 years.

The lawsuit came from more than a dozen environmental and health groups, including the American Public Health Association, the American Lung Association, the Center for Biological Diversity (CBD), the Clean Air Council, the Environmental Defense Fund (EDF), the Natural Resources Defense Council (NRDC), the Sierra Club, and the Union of Concerned Scientists.

The groups have asked the US Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit to review the EPA decision, which also eliminated requirements controlling greenhouse gas emissions in new cars and trucks. Urging a return to the status quo, the groups argued that the Trump administration is anti-science and illegally moving to benefit the fossil fuel industry, despite a mountain of evidence demonstrating the deadly consequences of unchecked pollution and climate change-induced floods, droughts, wildfires, and hurricanes.

“Undercutting the ability of the federal government to tackle the largest source of climate pollution is deadly serious,” Meredith Hankins, legal director for federal climate at NRDC, said in an EDF roundup of statements from plaintiffs.

The science is overwhelmingly clear, the groups argued, despite the Trump EPA attempting to muddy the waters by forming a since-disbanded working group of climate contrarians.

Trump is a longtime climate denier, as evidenced by a Euro News tracker monitoring his most controversial comments. Most recently, during a cold snap affecting much of the US, he predictably trolled environmentalists, writing on Truth Social, “could the Environmental Insurrectionists please explain—WHATEVER HAPPENED TO GLOBAL WARMING?”

The EPA’s final rule summary bragged that “this is the single largest deregulatory action in US history and will save Americans over $1.3 trillion” by 2055. Supposedly, carmakers will pass on any savings from no longer having to meet emissions requirements, giving Americans more access to affordable cars by shutting down expensive emissions and EV mandates “strangling” the auto industry. Sounding nothing like an agency created to monitor pollutants, a fact sheet on the final rule emphasized that Trump’s EPA “chooses consumer choice over climate change zealotry every time.”

Critics quickly slammed Trump’s claims that removing the endangerment finding would help the economy. Any savings from cheaper vehicles or reduced costs of charging infrastructure (as Americans ostensibly buy fewer EVs) would be offset by $1.4 trillion “in additional costs from increased fuel purchases, vehicle repair and maintenance, insurance, traffic congestion, and noise,” The Guardian reported. The EPA’s economic analysis also ignores public health costs, the groups suing alleged. David Pettit, an attorney at the CBD’s Climate Law Institute, slammed the EPA’s messaging as an attempt to sway consumers without explaining the true costs.

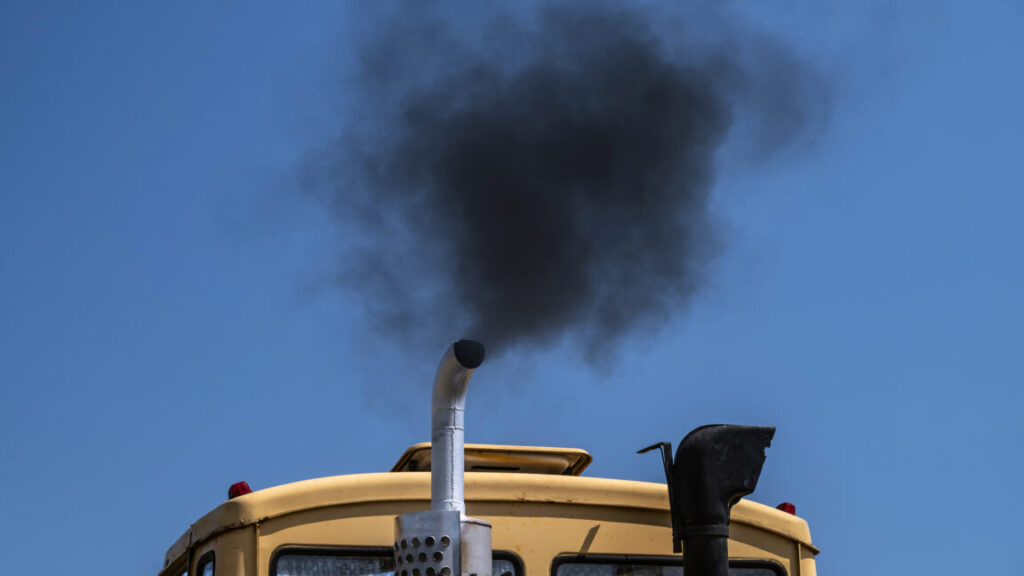

“Nobody but Big Oil profits from Trump trashing climate science and making cars and trucks guzzle and pollute more,” Pettit said. “Consumers will pay more to fill up, and our skies and oceans will fill up with more pollution.”

If the court sides with the EPA, “people everywhere will face more pollution, higher costs, and thousands of avoidable deaths,” Peter Zalzal, EDF’s associate vice president of clean air strategies, said.

EPA argued climate change evidence is “out of scope”

For environmentalists, the decision to sue the EPA was risky but necessary. By putting up a fight, they risk a court potentially reversing the 2009 Supreme Court ruling requiring the EPA to conduct the initial endangerment analysis and then regulate any pollution found from greenhouse gases.

Seemingly, that reversal is what the Trump administration has been angling for, hoping the case will reach the Supreme Court, which is more conservative today and perhaps less likely to read the Clean Air Act as broadly as the 2009 court.

It’s worth the risk, according to William Piermattei, the managing director of the Environmental Law Program at the University of Maryland Francis King Carey School of Law. He told The New York Times that environmentalists had no choice but to file the lawsuit and act on the public’s behalf.

Environmentalists “must challenge this,” Piermattei said. If they didn’t, they’d be “agreeing that we should not regulate greenhouse gasses under the Clean Air Act, full stop.” He suggested that “a majority of the public, does not agree with that statement at all.”

Since 2010, the EPA has found that the scientific basis for concluding that “elevated concentrations of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere may reasonably be anticipated to endanger the public health and welfare of current and future US generations is robust, voluminous, and compelling.” And since then, the evidence base has only grown, the groups suing said.

Trump used to seem intimidated by the “overwhelming” evidence, environmentalists have noted. During Trump’s prior term, he notably left the endangerment finding in place, perhaps expecting that the evidence was irrefutable. He’s now renewed that fight, arguing that the evidence should be set aside, so that courts can focus on whether Congress “must weigh in on ‘major questions’ that have significant political and economic implications” and serve as a check on the EPA.

In the EPA’s comments addressing public concerns about the agency ignoring evidence, the agency has already argued that evidence of climate change is “out of scope” since the EPA did not repeal the basis of the finding. Instead, the EPA claims it is merely challenging its own authority to continue to regulate the auto industry for harmful emissions, suggesting that only Congress has that authority.

The Clean Air Act “does not provide EPA statutory authority to prescribe motor vehicle emission standards for the purpose of addressing global climate change concerns,” the EPA said. “In the absence of such authority, the Endangerment Finding is not valid, and EPA cannot retain the regulations that resulted from it.”

Whether courts will agree that evidence supporting climate change is “out of scope” could determine whether the Supreme Court’s prior decision that compelled the endangerment finding is ultimately overturned. If that happens, subsequent administrations may struggle to issue a new endangerment finding to undo any potential damage. All eyes would then turn to Congress to pass a law to uphold protections.

EPA accused of abandoning its mission

By ignoring science, the EPA risks eroding public trust, according to Hana Vizcarra, a senior lawyer at the nonprofit Earthjustice, which is representing several groups in the litigation.

“With this action, EPA flips its mission on its head,” Vizcarra said. “It abandons its core mandate to protect human health and the environment to boost polluting industries and attempts to rewrite the law in order to do so.”

Groups appear confident that the courts will consider the science. Joanne Spalding, director of the Sierra Club’s Environmental Law Program, noted that the early 2000s litigation from the Sierra Club brought about the original EPA protections. She vowed that the Sierra Club would continue fighting to keep them.

“People should not be forced to suffer for this administration’s blind allegiance to the fossil fuel industry and corporate polluters,” Spalding said. “This shortsighted rollback is blatantly unlawful and their efforts to force this upon the American people will fail.”

Ankush Bansal, board president of Physicians for Social Responsibility, warned that courts cannot afford to ignore the evidence. The EPA’s “devastating decision” goes “against the science and testimony of countless scientists, health care professionals, and public health practitioners,” Bansal said. If upheld, the long-term consequences could seemingly bury courts in future legal battles.

“It will result in direct harm to the health of Americans throughout the country, particularly children, older adults, those with chronic illnesses, and other vulnerable populations, rural to urban, red and blue, of all races and incomes,” Bansal said. “The increased exposure to harmful pollutants and other greenhouse gas emissions from fossil fuel production and consumption will make America sicker, not healthier, less prosperous, not more, for generations to come.”

Lawsuit: EPA revoking greenhouse gas finding risks “thousands of avoidable deaths” Read More »