Password managers’ promise that they can’t see your vaults isn’t always true

Over the past 15 years, password managers have grown from a niche security tool used by the technology savvy into an indispensable security tool for the masses, with an estimated 94 million US adults—or roughly 36 percent of them—having adopted them. They store not only passwords for pension, financial, and email accounts, but also cryptocurrency credentials, payment card numbers, and other sensitive data.

All eight of the top password managers have adopted the term “zero knowledge” to describe the complex encryption system they use to protect the data vaults that users store on their servers. The definitions vary slightly from vendor to vendor, but they generally boil down to one bold assurance: that there is no way for malicious insiders or hackers who manage to compromise the cloud infrastructure to steal vaults or data stored in them. These promises make sense, given previous breaches of LastPass and the reasonable expectation that state-level hackers have both the motive and capability to obtain password vaults belonging to high-value targets.

A bold assurance debunked

Typical of these claims are those made by Bitwarden, Dashlane, and LastPass, which together are used by roughly 60 million people. Bitwarden, for example, says that “not even the team at Bitwarden can read your data (even if we wanted to).” Dashlane, meanwhile, says that without a user’s master password, “malicious actors can’t steal the information, even if Dashlane’s servers are compromised.” LastPass says that no one can access the “data stored in your LastPass vault, except you (not even LastPass).”

New research shows that these claims aren’t true in all cases, particularly when account recovery is in place or password managers are set to share vaults or organize users into groups. The researchers reverse-engineered or closely analyzed Bitwarden, Dashlane, and LastPass and identified ways that someone with control over the server—either administrative or the result of a compromise—can, in fact, steal data and, in some cases, entire vaults. The researchers also devised other attacks that can weaken the encryption to the point that ciphertext can be converted to plaintext.

“The vulnerabilities that we describe are numerous but mostly not deep in a technical sense,” the researchers from ETH Zurich and USI Lugano wrote. “Yet they were apparently not found before, despite more than a decade of academic research on password managers and the existence of multiple audits of the three products we studied. This motivates further work, both in theory and in practice.”

The researchers said in interviews that multiple other password managers they didn’t analyze as closely likely suffer from the same flaws. The only one they were at liberty to name was 1Password. Almost all the password managers, they added, are vulnerable to the attacks only when certain features are enabled.

The most severe of the attacks—targeting Bitwarden and LastPass—allow an insider or attacker to read or write to the contents of entire vaults. In some cases, they exploit weaknesses in the key escrow mechanisms that allow users to regain access to their accounts when they lose their master password. Others exploit weaknesses in support for legacy versions of the password manager. A vault-theft attack against Dashlane allowed reading but not modification of vault items when they were shared with other users.

Staging the old key switcheroo

One of the attacks targeting Bitwarden key escrow is performed during the enrollment of a new member of a family or organization. After a Bitwarden group admin invites the new member, the invitee’s client accesses a server and obtains a group symmetric key and the group’s public key. The client then encrypts the symmetric key with the group public key and sends it to the server. The resulting ciphertext is what’s used to recover the new user’s account. This data is never integrity-checked when it’s sent from the server to the client during an account enrollment session.

The adversary can exploit this weakness by replacing the group public key with one from a keypair created by the adversary. Since the adversary knows the corresponding private key, it can use it to decrypt the ciphertext and then perform an account recovery on behalf of the targeted user. The result is that the adversary can read and modify the entire contents of the member vault as soon as an invitee accepts an invitation from a family or organization.

Normally, this attack would work only when a group admin has enabled autorecovery mode, which, unlike a manual option, doesn’t require interaction from the member. But since the group policy the client downloads during the enrollment policy isn’t integrity-checked, adversaries can set recovery to auto, even if an admin had chosen a manual mode that requires user interaction.

Compounding the severity, the adversary in this attack also obtains a group symmetric key for all other groups the member belongs to since such keys are known to all group members. If any of the additional groups use account recovery, the adversary can obtain the members’ vaults for them, too. “This process can be repeated in a worm-like fashion, infecting all organizations that have key recovery enabled and have overlapping members,” the research paper explained.

A second attack targeting Bitwarden account recovery can be performed when a user rotates vault keys, an option Bitwarden recommends if a user believes their master password has been compromised. When account recovery is on (either manually or automatically), the user client regenerates the recovery ciphertext, which as described earlier involves obtaining a new public key that’s encrypted with the organization public key. The researchers denoted the group public key as pkorg. They denote the public key supplied by the adversary as pkadvorg, the recovery ciphertext as crec, and the user symmetric key as k′.

The paper explained:

The key point here is that pkorg is not retrieved from the user’s vault; rather the client performs a sync operation with the server to obtain it. Crucially, the organization data provided by this sync operation is not authenticated in any way. This thus provides the adversary with another opportunity to obtain a victim’s user key, by supplying a new public key pkadvorg, for which they know the skadvorg and setting the account recovery enrollment to true. The client will then send an account recovery ciphertext crec containing the new user key, which the adversary can decrypt to obtain k′.

The third attack on the Bitwarden account recovery allows an adversary to recover a user’s master key. It abuses key connector, a feature primarily used by enterprise customers.

More ways to pilfer vaults

The attack allowing theft of LastPass vaults also targets key escrow, specifically in the Teams and Teams 5 versions, when a member’s master key is reset by a privileged user known as a superadmin. The next time the member logs in through the LastPass browser extension, their client will retrieve an RSA keypair assigned to each superadmin in the organization, encrypt their new key with each one, and send the resulting ciphertext to each superadmin.

Because LastPass also fails to authenticate the superadmin keys, an adversary can once again replace the superadmin public key (pkadm) with their own public key (pkadvadm).

“In theory, only users in teams where password reset is enabled and who are selected for reset should be affected by this vulnerability,” the researchers wrote. “In practice, however, LastPass clients query the server at each login and fetch a list of admin keys. They then send the account recovery ciphertexts independently of enrollment status.” The attack, however, requires the user to log in to LastPass with the browser extension, not the standalone client app.

Several attacks allow reading and modification of shared vaults, which allow a user to share selected items with one or more other users. When Dashlane users share an item, their client apps sample a fresh symmetric key, which either directly encrypts the shared item or, when sharing with a group, encrypts group keys, which in turn encrypt the shared item. In either case, the newly created RSA keypair(s)—belonging to either the shared user or group—isn’t authenticated. The item is then encrypted with the private key(s).

An adversary can supply their own keypair and use the public key to encrypt the ciphertext sent to the recipients. The adversary then decrypts that ciphertext with their corresponding secret key to recover the shared symmetric key. With that, the adversary can read and modify all shared items. When sharing is used in either Bitwarden or LastPass, similar attacks are possible and lead to the same consequence.

Another avenue for attackers or adversaries with control of a server is to target the backward compatibility that all three password managers provide to support older, less-secure versions. Despite incremental changes designed to harden the apps against the very attacks described in the paper, all three password managers continue to support the versions without these improvements. This backward compatibility is a deliberate decision intended to prevent users who haven’t upgraded from losing access to their vaults.

The severity of these attacks is lower than that of the previous ones described, with the exception of one, which is possible against Bitwarden. Older versions of the password manager used a single symmetric key to encrypt and decrypt the user key from the server and items inside vaults. This design allowed for the possibility that an adversary could tamper with the contents. To add integrity checks, newer versions provide authenticated encryption by augmenting the symmetric key with an HMAC hash function.

To protect customers using older app versions, Bitwarden ciphertext has an attribute of either 0 or 1. A 0 designates authenticated encryption, while a 1 supports the older unauthenticated scheme. Older versions also use a key hierarchy that Bitwarden deprecated to harden the app. To support the old hierarchy, newer client versions generate a new RSA keypair for the user if the server doesn’t provide one. The newer version will proceed to encrypt the secret key portion with the master key if no user ciphertext is provided by the server.

This design opens Bitwarden to several attacks. The most severe, allowing reading (but not modification) of all items created after the attack is performed. At a simplified level, it works because the adversary can forge the ciphertext sent by the server and cause the client to use it to derive a user key known to the adversary.

The modification causes the use of CBC (cipher block chaining), a form of encryption that’s vulnerable to several attacks. An adversary can exploit this weaker form using a padding oracle attack and go on to retrieve the plaintext of the vault. Because HMAC protection remains intact, modification isn’t possible.

Surprisingly, Dashlane was vulnerable to a similar padding oracle attack. The researchers devised a complicated attack chain that would allow a malicious server to downgrade a Dashlane user’s vault to CBC and exfiltrate the contents. The researchers estimate that the attack would require about 125 days to decrypt the ciphertext.

Still other attacks against all three password managers allow adversaries to greatly reduce the selected number of hashing iterations—in the case of Bitwarden and LastPass, from a default of 600,000 to 2. Repeated hashing of master passwords makes them significantly harder to crack in the event of a server breach that allows theft of the hash. For all three password managers, the server sends the specified iteration count to the client, with no mechanism to ensure it meets the default number. The result is that the adversary receives a 200,000-fold increase in the time and resources required to crack the hash and obtain the user’s master password.

Attacking malleability

Three of the attacks—one against Bitwarden and two against LastPass—target what the researchers call “item-level encryption” or “vault malleability.” Instead of encrypting a vault in a single, monolithic blob, password managers often encrypt individual items, and sometimes individual fields within an item. These items and fields are all encrypted with the same key. The attacks exploit this design to steal passwords from select vault items.

An adversary mounts an attack by replacing the ciphertext in the URL field, which stores the link where a login occurs, with the ciphertext for the password. To enhance usability, password managers provide an icon that helps visually recognize the site. To do this, the client decrypts the URL field and sends it to the server. The server then fetches the corresponding icon. Because there’s no mechanism to prevent the swapping of item fields, the client decrypts the password instead of the URL and sends it to the server.

“That wouldn’t happen if you had different keys for different fields or if you encrypted the entire collection in one pass,” Kenny Paterson, one of the paper co-authors, said. “A crypto audit should spot it, but only if you’re thinking about malicious servers. The server is deviating from expected behavior.

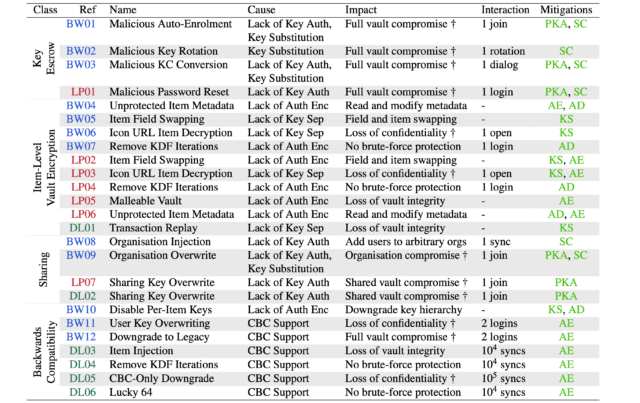

The following table summarizes the causes and consequences of the 25 attacks they devised:

Credit: Scarlata et al.

A psychological blind spot

The researchers acknowledge that the full compromise of a password manager server is a high bar. But they defend the threat model.

“Attacks on the provider server infrastructure can be prevented by carefully designed operational security measures, but it is well within the bounds of reason to assume that these services are targeted by sophisticated nation-state-level adversaries, for example via software supply-chain attacks or spearphishing,” they wrote. “Moreover, some of the service providers have a history of being breached—for example LassPass suffered branches in 2015 and 2022, and another serious security incident in 2021.

They went on to write: “While none of the breaches we are aware of involved reprogramming the server to make it undertake malicious actions, this goes just one step beyond attacks on password manager service providers that have been documented. Active attacks more broadly have been documented in the wild.”

Part of the challenge of designing password managers or any end-to-end encryption service is the tendency for a false sense of security of the client.

“It’s a psychological problem when you’re writing both client and server software,” Paterson explained. “You should write the client super defensively, but if you’re also writing the server, well of course your server isn’t going to send malformed packets or bad info. Why would you do that?”

Marketing gimmickry or not, “zero-knowledge” is here to stay

In many of the cases, engineers have already fixed the weaknesses described after receiving private reports from the researchers. Engineers are still patching other vulnerabilities. In statements, Bitwarden, Lastpass, and Dashlane representatives noted the high bar of the threat model, despite statements on their websites that assure customers their wares will withstand it. Along with 1Password representatives, they also noted that their products regularly receive stringent security audits and undergo red-team exercises.

A Bitwarden representative wrote:

Bitwarden continually evaluates and improves its software through internal review, third-party assessments, and external research. The ETH Zurich paper analyzes a threat model in which the server itself behaves maliciously and intentionally attempts to manipulate key material and configuration values. That model assumes full server compromise and adversarial behavior beyond standard operating assumptions for cloud services.

LastPass said, “We take a multi‑layered, ongoing approach to security assurance that combines independent oversight, continuous monitoring, and collaboration with the research community. Our cloud security testing is inclusive of the scenarios referenced in the malicious-server threat model outlined in the research.”

Specific measures include:

- Annual penetration testing (available through NDA) with reputable experts across all our apps and infrastructure.

- A bug bounty program

- Internal penetration testing to validate controls in our corporate environment

- Participation in AWS’s Security Improvement Program, where we conduct an annual in-depth review with AWS Security specialists and define a roadmap for continued improvement of our cloud infrastructure

- Continuous, dynamic application testing

A statement from Dashlane read, “Dashlane conducts rigorous internal and external testing to ensure the security of our product. When issues arise, we work quickly to mitigate any possible risk and ensure customers have clarity on the problem, our solution, and any required actions.”

1Password released a statement that read in part:

Our security team reviewed the paper in depth and found no new attack vectors beyond those already documented in our publicly available Security Design White Paper.

We are committed to continually strengthening our security architecture and evaluating it against advanced threat models, including malicious-server scenarios like those described in the research, and evolving it over time to maintain the protections our users rely on.

1Password also says that the zero-knowledge encryption it provides “means that no one but you—not even the company that’s storing the data—can access and decrypt your data. This protects your information even if the server where it’s held is ever breached.” In the company’s white paper linked above, 1Password seems to allow for this possibility when it says:

At present there’s no practical method for a user to verify the public key they’re encrypting data to belongs to their intended recipient. As a consequence it would be possible for a malicious or compromised 1Password server to provide dishonest public keys to the user, and run a successful attack. Under such an attack, it would be possible for the 1Password server to acquire vault encryption keys with little ability for users to detect or prevent it.

1Password’s statement also includes assurances that the service routinely undergoes rigorous security testing.

All four companies defended their use of the term “zero knowledge.” As used in this context, the term can be confused with zero-knowledge proofs, a completely unrelated cryptographic method that allows one party to prove to another party that they know a piece of information without revealing anything about the information itself. An example is a proof that shows a system can determine if someone is over 18 without having any knowledge of the precise birthdate.

The adulterated zero-knowledge term used by password managers appears to have come into being in 2007, when a company called Spider Oak used it to describe its cloud infrastructure for securely sharing sensitive data. Interestingly, Spider Oak formally retired the term a decade later after receiving user pushback.

“Sadly, it is just marketing hype, much like ‘military-grade encryption,’” Matteo Scarlata, lead author of the paper said. “Zero-knowledge seems to mean different things to different people (e.g., LastPass told us that they won’t adopt a malicious server threat model internally). Much unlike ‘end-to-end encryption,’ ‘zero-knowledge encryption’ is an elusive goal, so it’s impossible to tell if a company is doing it right.”

Dan Goodin is Senior Security Editor at Ars Technica, where he oversees coverage of malware, computer espionage, botnets, hardware hacking, encryption, and passwords. In his spare time, he enjoys gardening, cooking, and following the independent music scene. Dan is based in San Francisco. Follow him at here on Mastodon and here on Bluesky. Contact him on Signal at DanArs.82.

Password managers’ promise that they can’t see your vaults isn’t always true Read More »