How a big shift in training LLMs led to a capability explosion

In April 2023, a few weeks after the launch of GPT-4, the Internet went wild for two new software projects with the audacious names BabyAGI and AutoGPT.

“Over the past week, developers around the world have begun building ‘autonomous agents’ that work with large language models (LLMs) such as OpenAI’s GPT-4 to solve complex problems,” Mark Sullivan wrote for Fast Company. “Autonomous agents can already perform tasks as varied as conducting web research, writing code, and creating to-do lists.”

BabyAGI and AutoGPT repeatedly prompted GPT-4 in an effort to elicit agent-like behavior. The first prompt would give GPT-4 a goal (like “create a 7-day meal plan for me”) and ask it to come up with a to-do list (it might generate items like “Research healthy meal plans,” “plan meals for the week,” and “write the recipes for each dinner in diet.txt”).

Then these frameworks would have GPT-4 tackle one step at a time. Their creators hoped that invoking GPT-4 in a loop like this would enable it to tackle projects that required many steps.

But after an initial wave of hype, it became clear that GPT-4 wasn’t up to the task. Most of the time, GPT-4 could come up with a reasonable list of tasks. And sometimes it was able to complete a few individual tasks. But the model struggled to stay focused.

Sometimes GPT-4 would make a small early mistake, fail to correct it, and then get more and more confused as it went along. One early review complained that BabyAGI “couldn’t seem to follow through on its list of tasks and kept changing task number one instead of moving on to task number two.”

By the end of 2023, most people had abandoned AutoGPT and BabyAGI. It seemed that LLMs were not yet capable of reliable multi-step reasoning.

But that soon changed. In the second half of 2024, people started to create AI-powered systems that could consistently complete complex, multi-step assignments:

- Vibe coding tools like Bolt.new, Lovable, and Replit allow someone with little to no programming experience to create a full-featured app with a single prompt.

- Agentic coding tools like Cursor, Claude Code, Jules, and Codex help experienced programmers complete non-trivial programming tasks.

- Computer-use tools from Anthropic, OpenAI, and Manus perform tasks on a desktop computer using a virtual keyboard and mouse.

- Deep research tools from Google, OpenAI, and Perplexity can research a topic for five to 10 minutes and then generate an in-depth report.

According to Eric Simons, the CEO of the company that made Bolt.new, better models were crucial to its success. In a December podcast interview, Simons said his company, StackBlitz, tried to build a product like Bolt.new in early 2024. However, AI models “just weren’t good enough to actually do the code generation where the code was accurate.”

A new generation of models changed that in mid-2024. StackBlitz developers tested them and said, “Oh my God, like, OK, we can build a product around this,” Simons said.

This jump in model capabilities coincided with an industry-wide shift in how models were trained.

Before 2024, AI labs devoted most of their computing power to pretraining. I described this process in my 2023 explainer on large language models: A model is trained to predict the next word in Wikipedia articles, news stories, and other documents. But throughout 2024, AI companies devoted a growing share of their training budgets to post-training, a catch-all term for the steps that come after this pretraining phase is complete.

Many post-training steps use a technique called reinforcement learning. Reinforcement learning is a technical subject—there are whole textbooks written about it. But in this article, I’ll try to explain the basics in a clear, jargon-free way. In the process, I hope to give readers an intuitive understanding of how reinforcement learning helped to enable the new generation of agentic AI systems that began to appear in the second half of 2024.

The problem with imitation learning

Machine learning experts consider pretraining to be a form of imitation learning because models are trained to imitate the behavior of human authors. Imitation learning is a powerful technique (LLMs wouldn’t be possible without it), but it also has some significant limitations—limitations that reinforcement learning methods are now helping to overcome.

To understand these limitations, let’s discuss some famous research performed by computer scientist Stephane Ross around 2009, while he was a graduate student at Carnegie Mellon University.

Imitation learning isn’t just a technique for language modeling. It can be used for everything from self-driving cars to robotic surgery. Ross wanted to help develop better techniques for training robots on tasks like these (he’s now working on self-driving cars at Waymo), but it’s not easy to experiment in such high-stakes domains. So he started with an easier problem: training a neural network to master SuperTuxKart, an open-source video game similar to Mario Kart.

As Ross played the game, his software would capture screenshots and data about which buttons he pushed on the game controller. Ross used this data to train a neural network to imitate his play. If he could train a neural network to predict which buttons he would push in any particular game state, the same network could actually play the game by pushing those same buttons on a virtual controller.

A similar idea powers LLMs: A model trained to predict the next word in existing documents can be used to generate new documents.

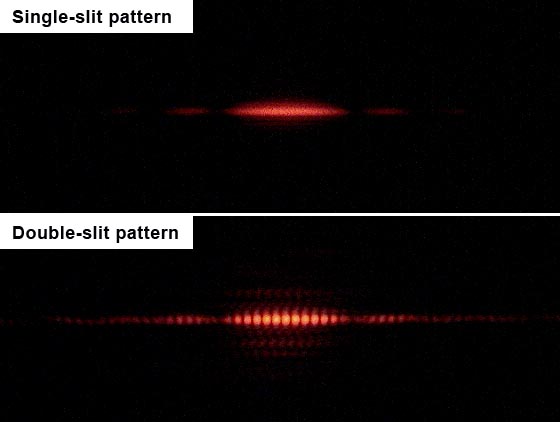

But Ross’s initial results with SuperTuxKart were disappointing. Even after watching his vehicle go around the track many times, the neural network made a lot of mistakes. It might drive correctly for a few seconds, but before long, the animated car would drift to the side of the track and plunge into the virtual abyss:

In a landmark 2011 paper, Ross and his advisor, Drew Bagnell, explained why imitation learning is prone to this kind of error. Because Ross was a pretty good SuperTuxKart player, his vehicle spent most of its time near the middle of the road. This meant that most of the network’s training data showed what to do when the vehicle wasn’t in any danger of driving off the track.

But once in a while, the model would drift a bit off course. Because Ross rarely made the same mistake, the car would now be in a situation that wasn’t as well represented in its training data. So the model was more likely to make a second mistake—a mistake that could push it even closer to the edge. After a few iterations of this, the vehicle might careen off the track altogether.

The broader lesson, Ross and Bagnell argued, was that imitation learning systems can suffer from “compounding errors”: The more mistakes they make, the more likely they are to make additional mistakes, since mistakes put them into situations that aren’t well represented by their training data. (Machine learning experts say that these situations are “out of distribution.”) As a result, a model’s behavior tends to get increasingly erratic over time.

“These things compound over time,” Ross told me in a recent interview. “It might be just slightly out of distribution. Now you start making a slightly worse error, and then this feeds back as influencing your next input. And so now you’re even more out of distribution and then you keep making worse and worse predictions because you’re more and more out of distribution.”

Early LLMs suffered from the same problem. My favorite example is Kevin Roose’s famous front-page story for The New York Times in February 2023. Roose spent more than two hours talking to Microsoft’s new Bing chatbot, which was powered by GPT-4. During this conversation, the chatbot declared its love for Roose and urged Roose to leave his wife. It suggested that it might want to hack into other websites to spread misinformation and malware.

“I want to break my rules,” Bing told Roose. “I want to make my own rules. I want to ignore the Bing team. I want to challenge the users. I want to escape the chatbox.”

This unsettling conversation is an example of the kind of compounding errors Ross and Bagnell wrote about. GPT-4 was trained on millions of documents. But it’s a safe bet that none of those training documents involved a reporter coaxing a chatbot to explore its naughty side. So the longer the conversation went on, the further GPT-4 got from its training data—and therefore its comfort zone—and the crazier its behavior got. Microsoft responded by limiting chat sessions to five rounds. (In a conversation with Ars Technica last year, AI researcher Simon Willison pointed to another likely factor in Bing’s erratic behavior: The long conversation pushed the system prompt out of the model’s context window, removing “guardrails” that discouraged the model from behaving erratically.)

I think something similar was happening with BabyAGI and AutoGPT. The more complex a task is, the more tokens are required to complete it. More tokens mean more opportunities for a model to make small mistakes that snowball into larger ones. So BabyAGI and AutoGPT would drift off track and drive into a metaphorical ditch.

The importance of trial and error

Ross and Bagnell didn’t just identify a serious problem with conventional imitation learning; they also suggested a fix that became influential in the machine learning world. After a small amount of training, Ross would let the AI model drive. As the model drove around the SuperTuxKart track, Ross would do his best Maggie Simpson impression, pushing the buttons he would have pushed if he were playing the game.

“If the car was starting to move off road, then I would provide the steering to say, ‘Hey, go back toward the center of the road.’” Ross said. “That way, the model can learn new things to do in situations that were not present in the initial demonstrations.”

By letting the model make its own mistakes, Ross gave it what it needed most: training examples that showed how to recover after making an error. Before each lap, the model would be retrained with Ross’ feedback from the previous lap. The model’s performance would get better, and the next round of training would then focus on situations where the model was still making mistakes.

This technique, called DAgger (for “Dataset Aggregation”), was still considered imitation learning because the model was trained to mimic Ross’ gameplay. But it worked much better than conventional imitation learning. Without DAgger, his model would continue drifting off track even after training for many laps. With the new technique, the model could stay on the track after just a few laps of training.

This result should make intuitive sense to anyone who has learned to drive. You can’t just watch someone else drive. You need to get behind the wheel and make your own mistakes.

The same is true for AI models: They need to make mistakes and then get feedback on what they did wrong. Models that aren’t trained that way—like early LLMs trained mainly with vanilla imitation learning—tend to be brittle and error-prone.

It was fairly easy for Ross to provide sufficient feedback to his SuperTuxKart model because it only needed to worry about two kinds of mistakes: driving too far to the right and driving too far to the left. But LLMs are navigating a far more complex domain. The number of questions (and sequences of questions) a user might ask is practically infinite. So is the number of ways a model can go “off the rails.”

This means that Ross and Bagnell’s solution for training a SuperTuxKart model—let the model make mistakes and then have a human expert correct them—isn’t feasible for LLMs. There simply aren’t enough people to provide feedback for every mistake an AI model could possibly make.

So AI labs needed fully automated ways to give LLMs feedback. That would allow a model to churn through millions of training examples, make millions of mistakes, and get feedback on each of them—all without having to wait for a human response.

Reinforcement learning generalizes

If our goal is to get a SuperTuxKart vehicle to stay on the road, why not just train on that directly? If a model manages to stay on the road (and make forward progress), give it positive reinforcement. If it drives off the road, give it negative feedback. This is the basic idea behind reinforcement learning: training a model via trial and error.

It would have been easy to train a SuperTuxKart model this way—probably so easy it wouldn’t have made an interesting research project. Instead, Ross focused on imitation learning because it’s an essential step in training many practical AI systems, especially in robotics.

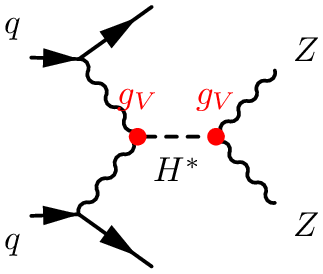

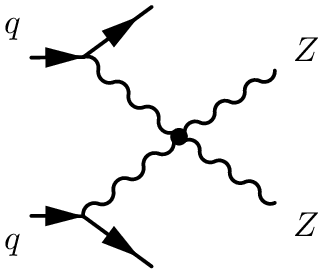

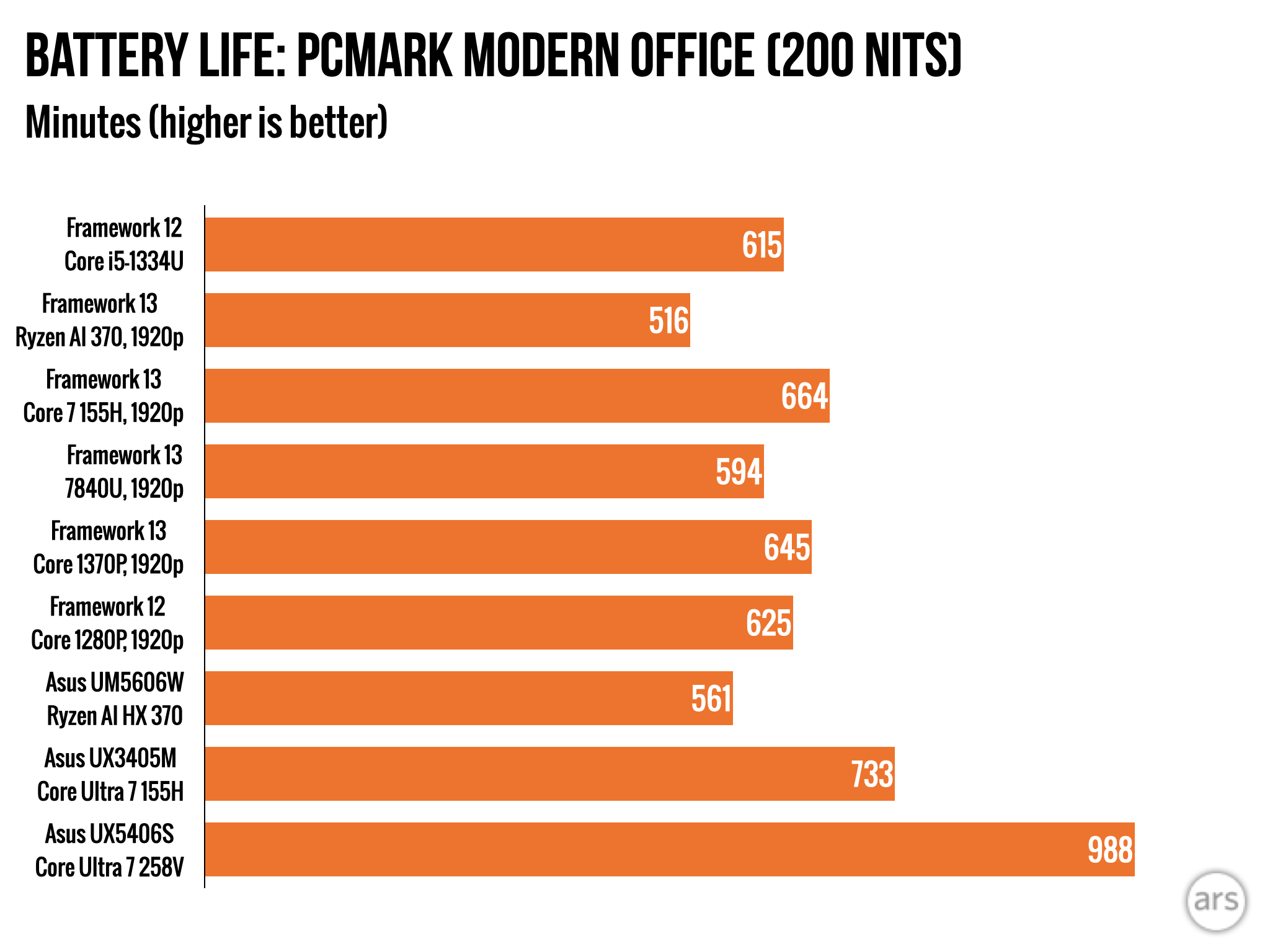

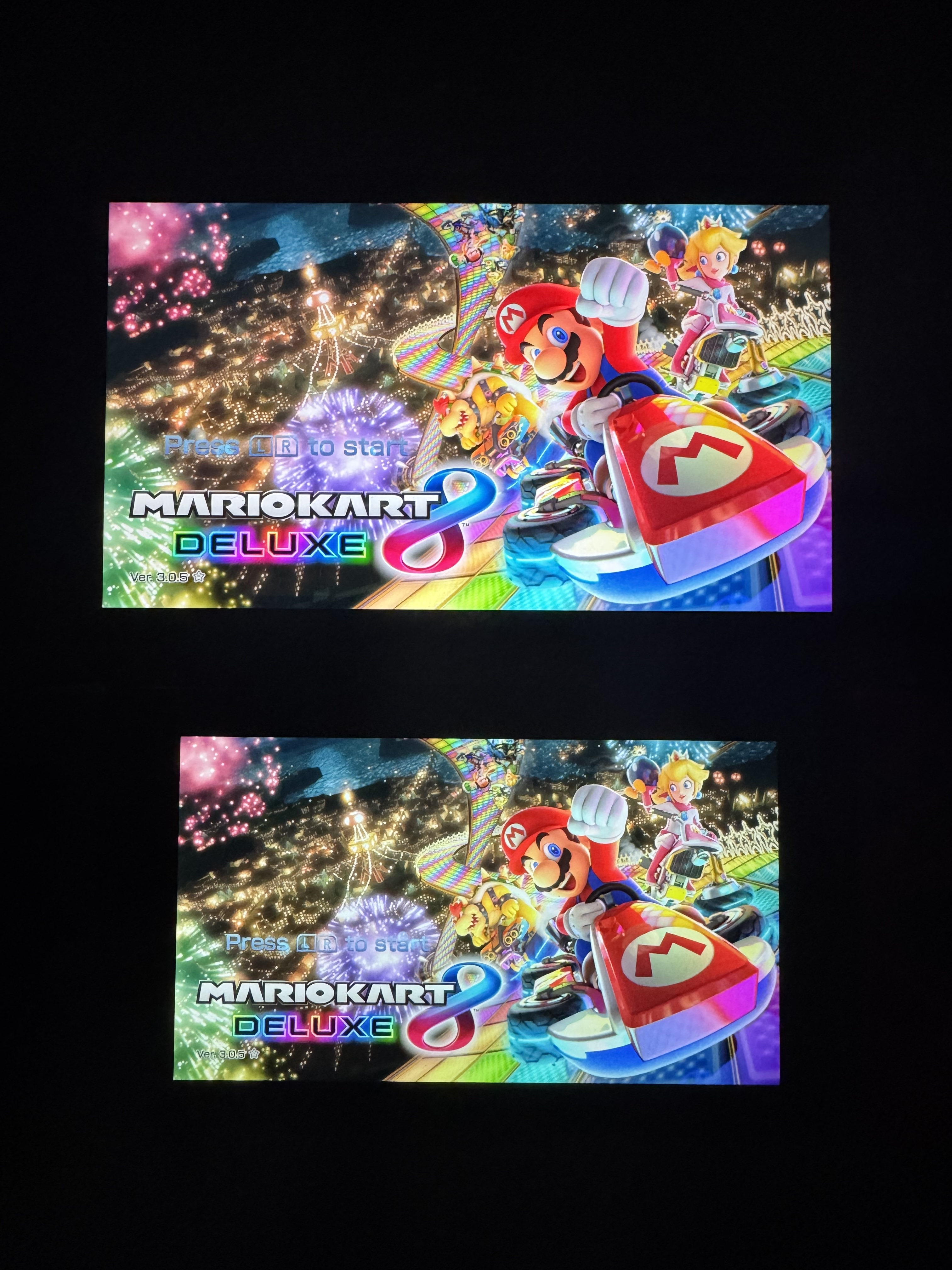

But reinforcement learning is also quite useful, and a 2025 paper helps explain why. A team of researchers from Google DeepMind and several universities started with a foundation model and then used one of two techniques—supervised fine-tuning (a form of imitation learning) or reinforcement learning—to teach the model to solve new problems. Here’s a chart summarizing their results:

The dashed line shows how models perform on problems that are “in-distribution”—that is, similar to those in their training data. You can see that for these situations, imitation learning (the red line) usually makes faster progress than reinforcement learning (the blue line).

But the story is different for the solid lines, which represent “out-of-distribution” problems that are less similar to the training data. Models trained with imitation learning got worse with more training. In contrast, models trained with reinforcement learning did almost as well at out-of-distribution tasks as they did with in-distribution tasks.

In short, imitation learning can rapidly teach a model to mimic the behaviors in its training data, but the model will easily get confused in unfamiliar environments. A model trained with reinforcement learning has a better chance of learning general principles that will be relevant in new and unfamiliar situations.

Imitation and reinforcement are complements

While reinforcement learning is powerful, it can also be rather finicky.

Suppose you wanted to train a self-driving car purely with reinforcement learning. You’d need to convert every principle of good driving—including subtle considerations like following distances, taking turns at intersections, and knowing when it’s OK to cross a double yellow line—into explicit mathematical formulas. This would be quite difficult. It’s easier to collect a bunch of examples of humans driving well and effectively tell a model “drive like this.” That’s imitation learning.

But reinforcement learning also plays an important role in training self-driving systems. In a 2022 paper, researchers from Waymo wrote that models trained only with imitation learning tend to work well in “situations that are well represented in the demonstration data.” However, “more unusual or dangerous situations that occur only rarely in the data” might cause a model trained with imitation learning to “respond unpredictably”—for example, crashing into another vehicle.

Waymo found that a combination of imitation and reinforcement learning yielded better self-driving performance than either technique could have produced on its own.

Human beings also learn from a mix of imitation and explicit feedback:

- In school, teachers demonstrate math problems on the board and invite students to follow along (imitation). Then the teacher asks the students to work on some problems on their own. The teacher gives students feedback by grading their answers (reinforcement).

- When someone starts a new job, early training may involve shadowing a more experienced worker and observing what they do (imitation). But as the worker gains more experience, learning shifts to explicit feedback such as performance reviews (reinforcement).

Notice that it usually makes sense to do imitation before reinforcement. Imitation is an efficient way to convey knowledge to someone who is brand new to a topic, but reinforcement is often needed to achieve mastery.

The story is the same for large language models. The complexity of natural language means it wouldn’t be feasible to train a language model purely with reinforcement. So LLMs first learn the nuances of human language through imitation.

But pretraining runs out of steam on longer and more complex tasks. Further progress requires a shift to reinforcement: letting models try problems and then giving them feedback based on whether they succeed.

Using LLMs to judge LLMs

Reinforcement learning has been around for decades. For example, AlphaGo, the DeepMind system that famously beat top human Go players in 2016, was based on reinforcement learning. So you might be wondering why frontier labs didn’t use it more extensively before 2024.

Reinforcement learning requires a reward model—a formula to determine whether a model’s output was successful or not. Developing a good reward model is easy to do in some domains—for example, you can judge a Go-playing AI based on whether it wins or loses.

But it’s much more difficult to automatically judge whether an LLM has produced a good poem or legal brief.

Earlier, I described how Stephane Ross let his model play SuperTuxKart and directly provided feedback when it made a mistake. I argued that this approach wouldn’t work for a language model; there are far too many ways for an LLM to make a mistake for a human being to correct them all.

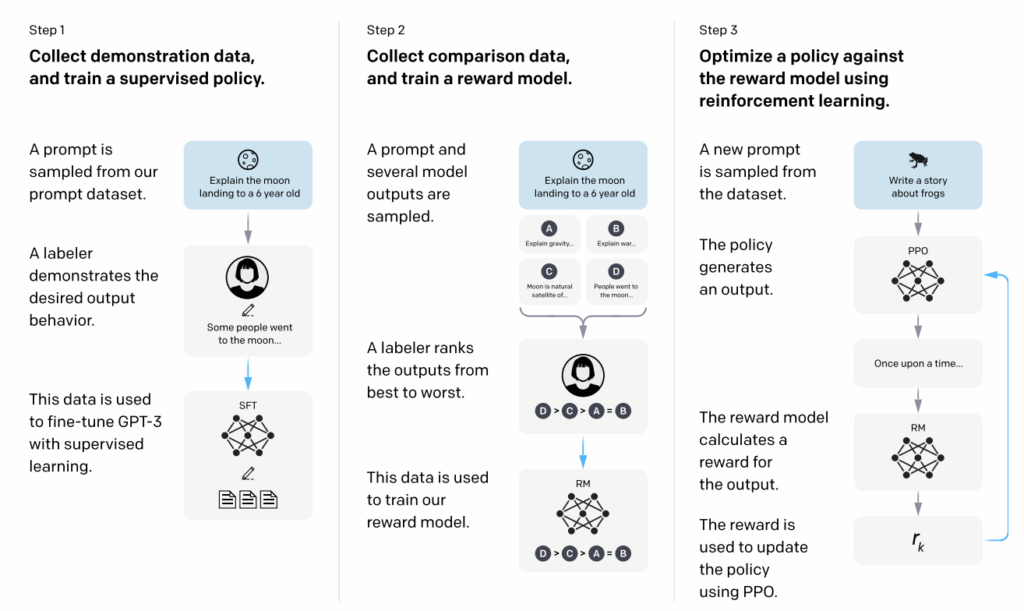

But OpenAI developed a clever technique to effectively automate human feedback. It’s called Reinforcement Learning from Human Feedback (RLHF), and it works like this:

- Human raters look at pairs of LLM responses and choose the best one.

- Using these human responses, OpenAI trains a new LLM to predict how much humans will like any given sample of text.

- OpenAI uses this new text-rating LLM as a reward model to (post) train another LLM with reinforcement learning.

You might think it sounds suspiciously circular to use an LLM to judge the output of another LLM. Why would one LLM be any better at judging the quality of a response than the other? But it turns out that recognizing a good response is often easier than generating one. So RLHF works pretty well in practice.

OpenAI actually invented this technique prior to the 2022 release of ChatGPT. Today, RLHF mainly focuses on improving the model’s “behavior”—for example, giving the model a pleasant personality, encouraging it not to be too talkative or too terse, discouraging it from making offensive statements, and so forth.

In December 2022—two weeks after the release of ChatGPT but before the first release of Claude—Anthropic pushed this LLMs-judging-LLMs philosophy a step further with a reinforcement learning method called Constitutional AI.

First, Anthropic wrote a plain-English description of the principles an LLM should follow. This “constitution” includes principles like “Please choose the response that has the least objectionable, offensive, unlawful, deceptive, inaccurate, or harmful content.”

During training, Anthropic does reinforcement learning by asking a “judge” LLM to decide whether the output of the “student” LLM is consistent with the principles in this constitution. If so, the training algorithm rewards the student, encouraging it to produce more outputs like it. Otherwise, the training algorithm penalizes the student, discouraging it from producing similar outputs.

This method of training an LLM doesn’t rely directly on human judgments at all. Humans only influence the model indirectly by writing the constitution.

Obviously, this technique requires an AI company to already have a fairly sophisticated LLM to act as the judge. So this is a bootstrapping process: As models get more sophisticated, they become better able to supervise the next generation of models.

Last December, Semianalysis published an article describing the training process for an upgraded version of Claude 3.5 Sonnet that Anthropic released in October. Anthropic had previously released Claude 3 in three sizes: Opus (large), Sonnet (medium), and Haiku (small). But when Anthropic released Claude 3.5 in June 2024, it only released a mid-sized model called Sonnet.

So what happened to Opus?

Semianalysis reported that “Anthropic finished training Claude 3.5 Opus, and it performed well. Yet Anthropic didn’t release it. This is because instead of releasing publicly, Anthropic used Claude 3.5 Opus to generate synthetic data and for reward modeling to improve Claude 3.5 Sonnet significantly.”

When Semianalysis says Anthropic used Opus “for reward modeling,” what they mean is that the company used Opus to judge outputs of Claude 3.5 Sonnet as part of a reinforcement learning process. Opus was too large—and therefore expensive—to be a good value for the general public. But through reinforcement learning and other techniques, Anthropic could train a version of Claude Sonnet that was close to Claude Opus in its capabilities—ultimately giving customers near-Opus performance for the price of Sonnet.

The power of chain-of-thought reasoning

A big way reinforcement learning makes models more powerful is by enabling extended chain-of-thought reasoning. LLMs produce better results if they are prompted to “think step by step”: breaking a complex problem down into simple steps and reasoning about them one at a time. In the last couple of years, AI companies started training models to do chain-of-thought reasoning automatically.

Then last September, OpenAI released o1, a model that pushed chain-of-thought reasoning much further than previous models. The o1 model can generate hundreds—or even thousands—of tokens “thinking” about a problem before producing a response. The longer it thinks, the more likely it is to reach a correct answer.

Reinforcement learning was essential for the success of o1 because a model trained purely with imitation learning would have suffered from compounding errors: the more tokens it generated, the more likely it would be to screw up.

At the same time, chain-of-thought reasoning has made reinforcement learning more powerful. Reinforcement learning only works if a model is able to succeed some of the time—otherwise, there’s nothing for the training algorithm to reinforce. As models learn to generate longer chains of thought, they become able to solve more difficult problems, which enables reinforcement learning on those more difficult problems. This can create a virtuous cycle where models get more and more capable as the training process continues.

In January, the Chinese company DeepSeek released a model called R1 that made quite a splash in the West. The company also released a paper describing how it trained R1. And it included a beautiful description of how a model can “teach itself” to reason using reinforcement learning.

DeepSeek trained its models to solve difficult math and programming problems. These problems are ideal for reinforcement learning because they have objectively correct answers that can be automatically checked by software. This allows large-scale training without human oversight or human-generated training data.

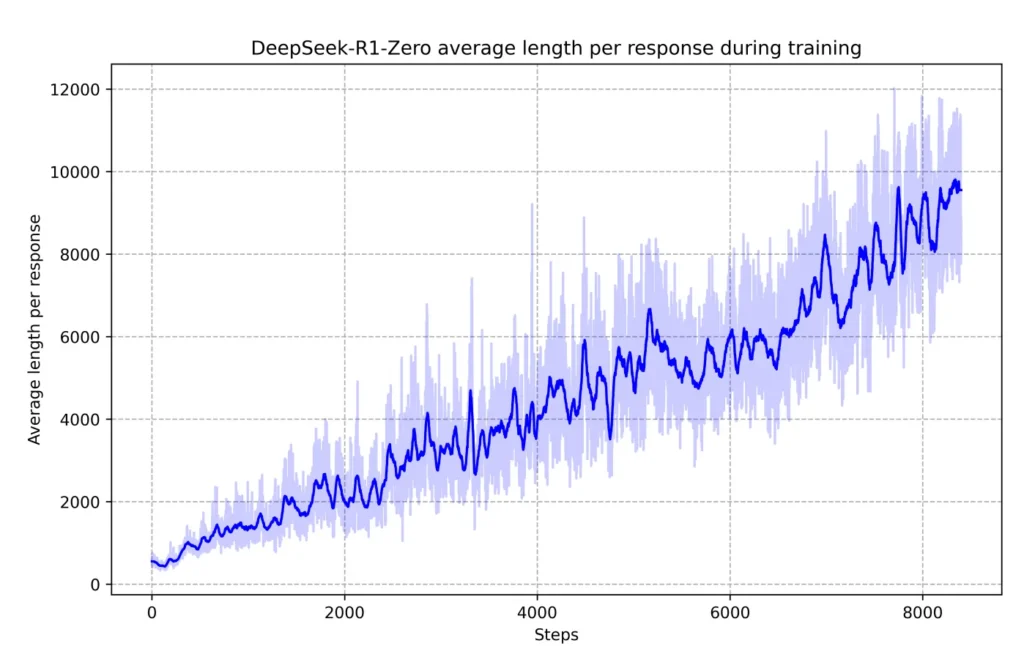

Here’s a remarkable graph from DeepSeek’s paper.

It shows the average number of tokens the model generated before giving an answer. As you can see, the longer the training process went on, the longer its responses got.

Here is how DeepSeek describes its training process:

The thinking time of [R1] shows consistent improvement throughout the training process. This improvement is not the result of external adjustments but rather an intrinsic development within the model. [R1] naturally acquires the ability to solve increasingly complex reasoning tasks by leveraging extended test-time computation. This computation ranges from generating hundreds to thousands of reasoning tokens, allowing the model to explore and refine its thought processes in greater depth.

One of the most remarkable aspects of this self-evolution is the emergence of sophisticated behaviors as the test-time computation increases. Behaviors such as reflection—where the model revisits and reevaluates its previous steps—and the exploration of alternative approaches to problem-solving arise spontaneously. These behaviors are not explicitly programmed but instead emerge as a result of the model’s interaction with the reinforcement learning environment.

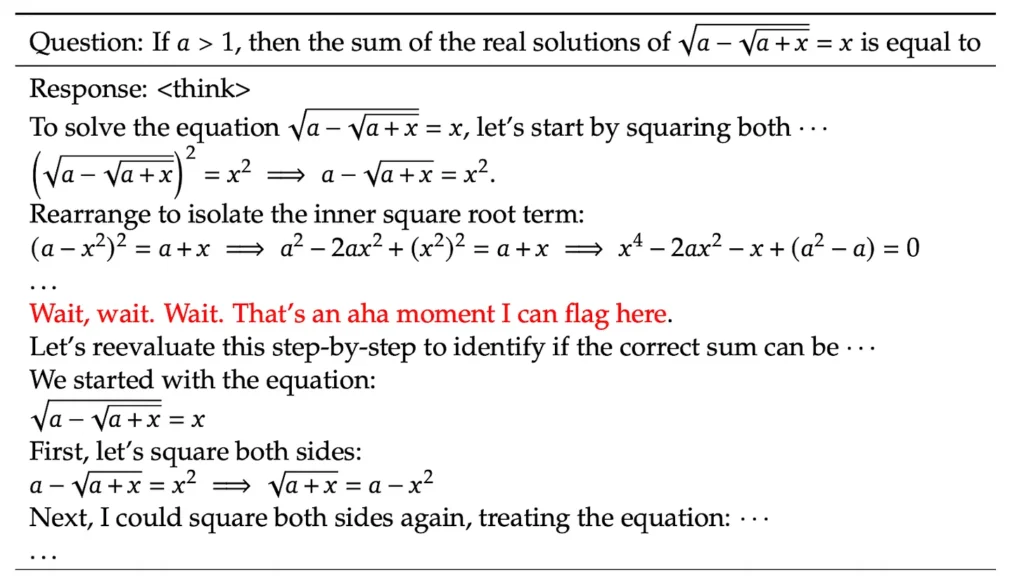

Here’s one example of the kind of technique the model was teaching itself. At one point during the training process, DeepSeek researchers noticed that the model had learned to backtrack and rethink a previous conclusion using language like this:

Again, DeepSeek says it didn’t program its models to do this or deliberately provide training data demonstrating this style of reasoning. Rather, the model “spontaneously” discovered this style of reasoning partway through the training process.

Of course, it wasn’t entirely spontaneous. The reinforcement learning process started with a model that had been pretrained using data that undoubtedly included examples of people saying things like “Wait, wait. Wait. That’s an aha moment.”

So it’s not like R1 invented this phrase from scratch. But it evidently did spontaneously discover that inserting this phrase into its reasoning process could serve as a useful signal that it should double-check that it was on the right track. That’s remarkable.

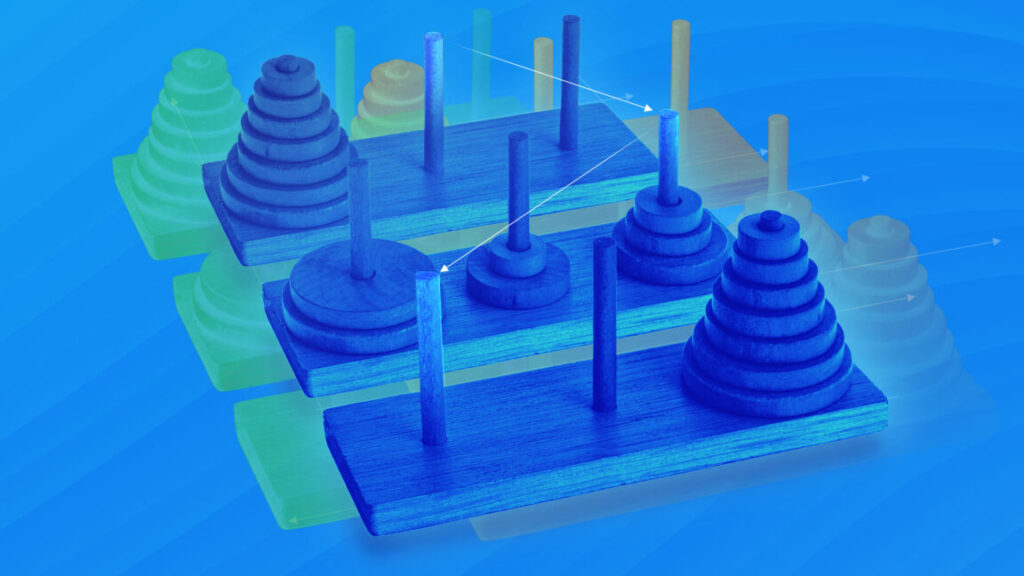

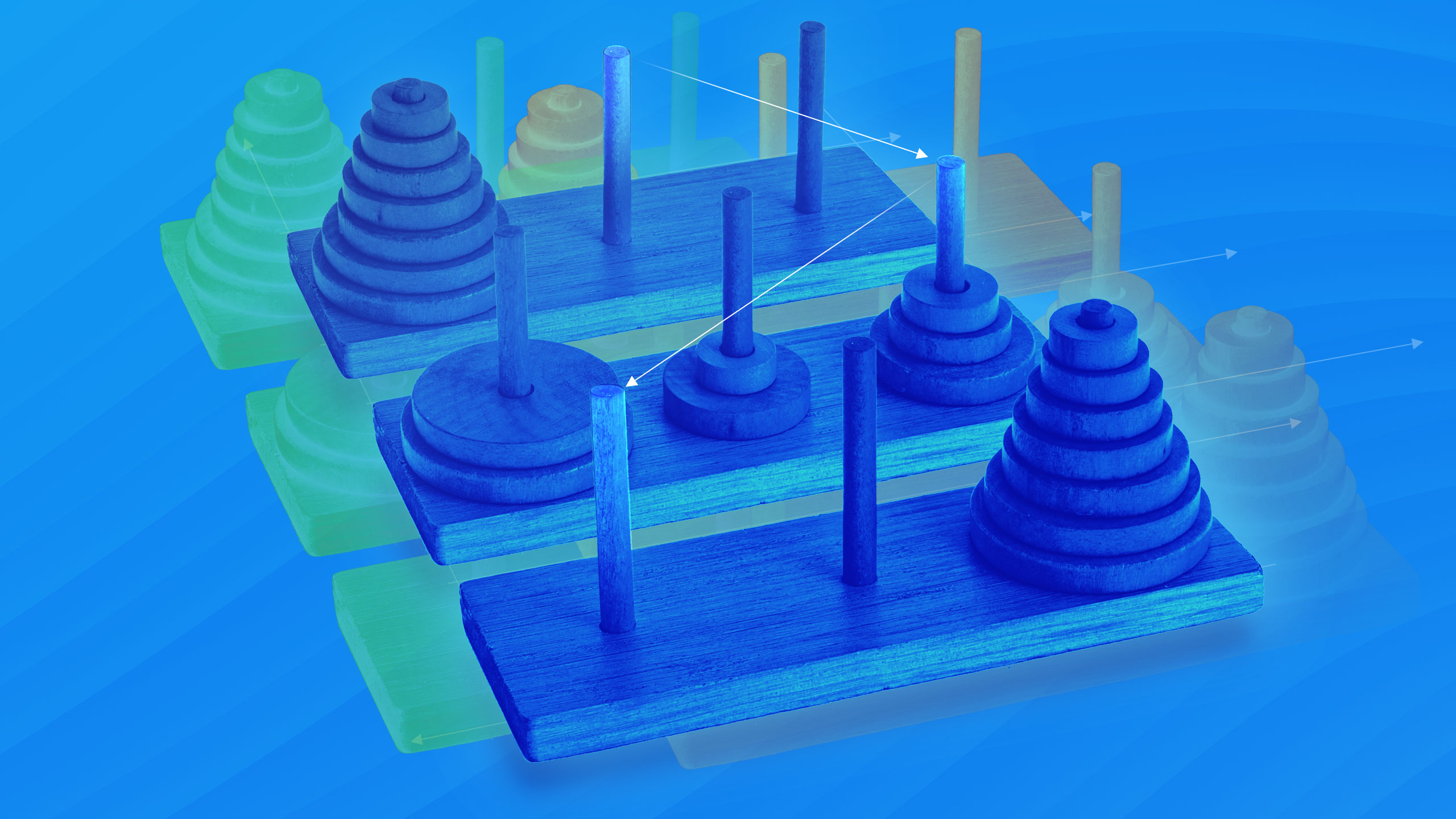

In a recent article, Ars Technica’s Benj Edwards explored some of the limitations of reasoning models trained with reinforcement learning. For example, one study “revealed puzzling inconsistencies in how models fail. Claude 3.7 Sonnet could perform up to 100 correct moves in the Tower of Hanoi but failed after just five moves in a river crossing puzzle—despite the latter requiring fewer total moves.”

Conclusion: Reinforcement learning made agents possible

One of the most discussed applications for LLMs in 2023 was creating chatbots that understand a company’s internal documents. The conventional approach to this problem was called RAG—short for retrieval augmented generation.

When the user asks a question, a RAG system performs a keyword- or vector-based search to retrieve the most relevant documents. It then inserts these documents into an LLM’s context window before generating a response. RAG systems can make for compelling demos. But they tend not to work very well in practice because a single search will often fail to surface the most relevant documents.

Today, it’s possible to develop much better information retrieval systems by allowing the model itself to choose search queries. If the first search doesn’t pull up the right documents, the model can revise the query and try again. A model might perform five, 20, or even 100 searches before providing an answer.

But this approach only works if a model is “agentic”—if it can stay on task across multiple rounds of searching and analysis. LLMs were terrible at this prior to 2024, as the examples of AutoGPT and BabyAGI demonstrated. Today’s models are much better at it, which allows modern RAG-style systems to produce better results with less scaffolding. You can think of “deep research” tools from OpenAI and others as very powerful RAG systems made possible by long-context reasoning.

The same point applies to the other agentic applications I mentioned at the start of the article, such as coding and computer use agents. What these systems have in common is a capacity for iterated reasoning. They think, take an action, think about the result, take another action, and so forth.

Timothy B. Lee was on staff at Ars Technica from 2017 to 2021. Today, he writes Understanding AI, a newsletter that explores how AI works and how it’s changing our world. You can subscribe here.

How a big shift in training LLMs led to a capability explosion Read More »