How to draft a will to avoid becoming an AI ghost—it’s not easy

As artificial intelligence has advanced, AI tools have emerged to make it possible to easily create digital replicas of lost loved ones, which can be generated without the knowledge or consent of the person who died.

Trained on the data of the dead, these tools, sometimes called grief bots or AI ghosts, may be text-, audio-, or even video-based. Chatting provides what some mourners feel is a close approximation to ongoing interactions with the people they love most. But the tech remains controversial, perhaps complicating the grieving process while threatening to infringe upon the privacy of the deceased, whose data could still be vulnerable to manipulation or identity theft.

Because of suspected harms and perhaps a general repulsion to the idea of it, not everybody wants to become an AI ghost.

After a realistic video simulation was recently used to provide a murder victim’s impact statement in court, Futurism summed up social media backlash, noting that the use of AI was “just as unsettling as you think.” And it’s not the first time people have expressed discomfort with the growing trend. Last May, The Wall Street Journal conducted a reader survey seeking opinions on the ethics of so-called AI resurrections. Responding, a California woman, Dorothy McGarrah, suggested there should be a way to prevent AI resurrections in your will.

“Having photos or videos of lost loved ones is a comfort. But the idea of an algorithm, which is as prone to generate nonsense as anything lucid, representing a deceased person’s thoughts or behaviors seems terrifying. It would be like generating digital dementia after your loved ones’ passing,” McGarrah said. “I would very much hope people have the right to preclude their images being used in this fashion after death. Perhaps something else we need to consider in estate planning?”

For experts in estate planning, the question may start to arise as more AI ghosts pop up. But for now, writing “no AI resurrections” into a will remains a complicated process, experts suggest, and such requests may not be honored by all unless laws are changed to reinforce a culture of respecting the wishes of people who feel uncomfortable with the idea of haunting their favorite people through AI simulations.

Can you draft a will to prevent AI resurrection?

Ars contacted several law associations to find out if estate planners are seriously talking about AI ghosts. Only the National Association of Estate Planners and Councils responded; it connected Ars to Katie Sheehan, an expert in the estate planning field who serves as a managing director and wealth strategist for Crestwood Advisors.

Sheehan told Ars that very few estate planners are prepared to answer questions about AI ghosts. She said not only does the question never come up in her daily work, but it’s also “essentially uncharted territory for estate planners since AI is relatively new to the scene.”

“I have not seen any documents drafted to date taking this into consideration, and I review estate plans for clients every day, so that should be telling,” Sheehan told Ars.

Although Sheehan has yet to see a will attempting to prevent AI resurrection, she told Ars that there could be a path to make it harder for someone to create a digital replica without consent.

“You certainly could draft into a power of attorney (for use during lifetime) and a will (for use post death) preventing the fiduciary (attorney in fact or executor) from lending any of your texts, voice, image, writings, etc. to any AI tools and prevent their use for any purpose during life or after you pass away, and/or lay the ground rules for when they can and cannot be used after you pass away,” Sheehan told Ars.

“This could also invoke issues with contract, property and intellectual property rights, and right of publicity as well if AI replicas (image, voice, text, etc.) are being used without authorization,” Sheehan said.

And there are likely more protections for celebrities than for everyday people, Sheehan suggested.

“As far as I know, there is no law” preventing unauthorized non-commercial digital replicas, Sheehan said.

Widely adopted by states, the Revised Uniform Fiduciary Access to Digital Assets Act—which governs who gets access to online accounts of the deceased, like social media or email accounts—could be helpful but isn’t a perfect remedy.

That law doesn’t directly “cover someone’s AI ghost bot, though it may cover some of the digital material some may seek to use to create a ghost bot,” Sheehan said.

“Absent any law” blocking non-commercial digital replicas, Sheehan expects that people’s requests for “no AI resurrections” will likely “be dealt with in the courts and governed by the terms of one’s estate plan, if it is addressed within the estate plan.”

Those potential fights seemingly could get hairy, as “it may be some time before we get any kind of clarity or uniform law surrounding this,” Sheehan suggested.

In the future, Sheehan said, requests prohibiting digital replicas may eventually become “boilerplate language in almost every will, trust, and power of attorney,” just as instructions on digital assets are now.

As “all things AI become more and more a part of our lives,” Sheehan said, “some aspects of AI and its components may also be woven throughout the estate plan regularly.”

“But we definitely aren’t there yet,” she said. “I have had zero clients ask about this.”

Requests for “no AI resurrections” will likely be ignored

Whether loved ones would—or even should—respect requests blocking digital replicas appears to be debatable. But at least one person who built a grief bot wished he’d done more to get his dad’s permission before moving forward with his own creation.

A computer science professor at the University of Washington Bothell, Muhammad Aurangzeb Ahmad, was one of the earliest AI researchers to create a grief bot more than a decade ago after his father died. He built the bot to ensure that his future kids would be able to interact with his father after seeing how incredible his dad was as a grandfather.

When Ahmad started his project, there was no ChatGPT or other advanced AI model to serve as the foundation, so he had to train his own model based on his dad’s data. Putting immense thought into the effort, Ahmad decided to close off the system from the rest of the Internet so that only his dad’s memories would inform the model. To prevent unauthorized chats, he kept the bot on a laptop that only his family could access.

Ahmad was so intent on building a digital replica that felt just like his dad that it didn’t occur to him until after his family started using the bot that he never asked his dad if this was what he wanted. Over time, he realized that the bot was biased to his view of his dad, perhaps even feeling off to his siblings who had a slightly different relationship with their father. It’s unclear if his dad would similarly view the bot as preserving just one side of him.

Ultimately, Ahmad didn’t regret building the bot, and he told Ars he thinks his father “would have been fine with it.”

But he did regret not getting his father’s consent.

For people creating bots today, seeking consent may be appropriate if there’s any chance the bot may be publicly accessed, Ahmad suggested. He told Ars that he would never have been comfortable with the idea of his dad’s digital replica being publicly available because the question of an “accurate representation” would come even more into play, as malicious actors could potentially access it and sully his dad’s memory.

Today, anybody can use ChatGPT’s model to freely create a similar bot with their own loved one’s data. And a wide range of grief tech services have popped up online, including HereAfter AI, SeanceAI, and StoryFile, Axios noted in an October report detailing the latest ways “AI could be used to ‘resurrect’ loved ones.” As this trend continues “evolving very fast,” Ahmad told Ars that estate planning is probably the best way to communicate one’s AI ghost preferences.

But in a recently published article on “The Law of Digital Resurrection,” law professor Victoria Haneman warned that “there is no legal or regulatory landscape against which to estate plan to protect those who would avoid digital resurrection, and few privacy rights for the deceased. This is an intersection of death, technology, and privacy law that has remained relatively ignored until recently.”

Haneman agreed with Sheehan that “existing protections are likely sufficient to protect against unauthorized commercial resurrections”—like when actors or musicians are resurrected for posthumous performances. However, she thinks that for personal uses, digital resurrections may best be blocked not through estate planning but by passing a “right to deletion” that would focus on granting the living or next of kin the rights to delete the data that could be used to create the AI ghost rather than regulating the output.

A “right to deletion” could help people fight inappropriate uses of their loved ones’ data, whether AI is involved or not. After her article was published, a lawyer reached out to Haneman about a client’s deceased grandmother whose likeness was used to create a meme of her dancing in a church. The grandmother wasn’t a public figure, and the client had no idea “why or how somebody decided to resurrect her deceased grandmother,” Haneman told Ars.

Although Haneman sympathized with the client, “if it’s not being used for a commercial purpose, she really has no control over this use,” Haneman said. “And she’s deeply troubled by this.”

Haneman’s article offers a rare deep dive into the legal topic. It sensitively maps out the vague territory of digital rights of the dead and explains how those laws—or the lack thereof—interact with various laws dealing with death, from human remains to property rights.

In it, Haneman also points out that, on balance, the rights of the living typically outweigh the rights of the dead, and even specific instructions on how to handle human remains aren’t generally considered binding. Some requests, like organ donation that can benefit the living, are considered critical, Haneman noted. But there are mixed results on how courts enforce other interests of the dead—like a famous writer’s request to destroy all unpublished work or a pet lover’s insistence to destroy their cat or dog at death.

She told Ars that right now, “a lot of people are like, ‘Why do I care if somebody resurrects me after I’m dead?’ You know, ‘They can do what they want.’ And they think that, until they find a family member who’s been resurrected by a creepy ex-boyfriend or their dead grandmother’s resurrected, and then it becomes a different story.”

Existing law may protect “the privacy interests of the loved ones of the deceased from outrageous or harmful digital resurrections of the deceased,” Haneman noted, but in the case of the dancing grandma, her meme may not be deemed harmful, no matter how much it troubles the grandchild to see her grandma’s memory warped.

Limited legal protections may not matter so much if, culturally, communities end up developing a distaste for digital replicas, particularly if it becomes widely viewed as disrespectful to the dead, Haneman suggested. Right now, however, society is more fixated on solving other problems with deepfakes rather than clarifying the digital rights of the dead. That could be because few people have been impacted so far, or it could also reflect a broader cultural tendency to ignore death, Haneman told Ars.

“We don’t want to think about our own death, so we really kind of brush aside whether or not we care about somebody else being digitally resurrected until it’s in our face,” Haneman said.

Over time, attitudes may change, especially if the so-called “digital afterlife industry” takes off. And there is some precedent that the law could be changed to reinforce any culture shift.

“The throughline revealed by the law of the dead is that a sacred trust exists between the living and the deceased, with an emphasis upon protecting common humanity, such that data afforded no legal status (or personal data of the deceased) may nonetheless be treated with dignity and receive some basic protections,” Haneman wrote.

An alternative path to prevent AI resurrection

Preventing yourself from becoming an AI ghost seemingly now falls in a legal gray zone that policymakers may need to address.

Haneman calls for a solution that doesn’t depend on estate planning, which she warned “is a structurally inequitable and anachronistic approach that maximizes social welfare only for those who do estate planning.” More than 60 percent of Americans die without a will, often including “those without wealth,” as well as women and racial minorities who “are less likely to die with a valid estate plan in effect,” Haneman reported.”We can do better in a technology-based world,” Haneman wrote. “Any modern framework should recognize a lack of accessibility as an obstacle to fairness and protect the rights of the most vulnerable through approaches that do not depend upon hiring an attorney and executing an estate plan.”

Rather than twist the law to “recognize postmortem privacy rights,” Haneman advocates for a path for people resistant to digital replicas that focuses on a right to delete the data that would be used to create the AI ghost.

“Put simply, the deceased may exert control over digital legacy through the right to deletion of data but may not exert broader rights over non-commercial digital resurrection through estate planning,” Haneman recommended.

Sheehan told Ars that a right to deletion would likely involve estate planners, too.

“If this is not addressed in an estate planning document and not specifically addressed in the statute (or deemed under the authority of the executor via statute), then the only way to address this would be to go to court,” Sheehan said. “Even with a right of deletion, the deceased would need to delete said data before death or authorize his executor to do so post death, which would require an estate planning document, statutory authority, or court authority.”

Haneman agreed that for many people, estate planners would still be involved, recommending that “the right to deletion would ideally, from the perspective of estate administration, provide for a term of deletion within 12 months.” That “allows the living to manage grief and open administration of the estate before having to address data management issues,” Haneman wrote, and perhaps adequately balances “the interests of society against the rights of the deceased.”

To Haneman, it’s also the better solution for the people left behind because “creating a right beyond data deletion to curtail unauthorized non-commercial digital resurrection creates unnecessary complexity that overreaches, as well as placing the interests of the deceased over those of the living.”

Future generations may be raised with AI ghosts

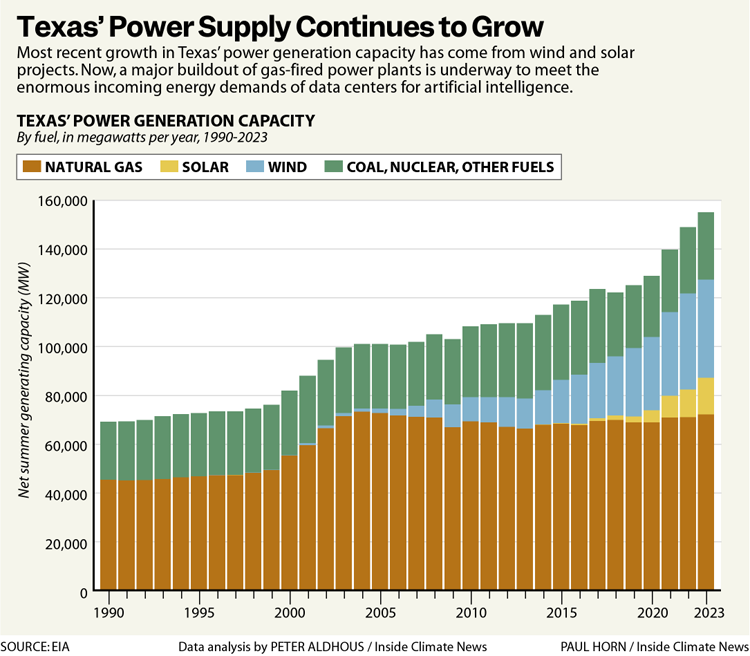

If a dystopia that experts paint comes true, Big Tech companies may one day profit by targeting grieving individuals to seize the data of the dead, which could be more easily abused since it’s granted fewer rights than data of the living.

Perhaps in that future, critics suggest, people will be tempted into free trials in moments when they’re missing their loved ones most, then forced to either pay a subscription to continue accessing the bot or else perhaps be subjected to ad-based models where their chats with AI ghosts may even feature ads in the voices of the deceased.

Today, even in a world where AI ghosts aren’t yet compelling ad clicks, some experts have warned that interacting with AI ghosts could cause mental health harms, New Scientist reported, especially if the digital afterlife industry isn’t carefully designed, AI ethicists warned. Some people may end up getting stuck maintaining an AI ghost if it’s left behind as a gift, and ethicists suggested that the emotional weight of that could also eventually take a negative toll. While saying goodbye is hard, letting go is considered a critical part of healing during the mourning process, and AI ghosts may make that harder.

But the bots can be a helpful tool to manage grief, some experts suggest, provided that their use is limited to allow for a typical mourning process or combined with therapy from a trained professional, Al Jazeera reported. Ahmad told Ars that working on his bot has not only kept his father close to him but also helped him think more deeply about relationships and memory.

Haneman noted that people have many ways of honoring the dead. Some erect statues, and others listen to saved voicemails or watch old home movies. For some, just “smelling an old sweater” is a comfort. And creating digital replicas, as creepy as some people might find them, is not that far off from these traditions, Haneman said.

“Feeding text messages and emails into existing AI platforms such as ChatGPT and asking the AI to respond in the voice of the deceased is simply a change in degree, not in kind,” Haneman said.

For Ahmad, the decision to create a digital replica of his dad was a learning experience, and perhaps his experience shows why any family or loved one weighing the option should carefully consider it before starting the process.

In particular, he warns families to be careful introducing young kids to grief bots, as they may not be able to grasp that the bot is not a real person. When he initially saw his young kids growing confused with whether their grandfather was alive or not—the introduction of the bot was complicated by the early stages of the pandemic, a time when they met many relatives virtually—he decided to restrict access to the bot until they were older. For a time, the bot only came out for special events like birthdays.

He also realized that introducing the bot also forced him to have conversations about life and death with his kids at ages younger than he remembered fully understanding those concepts in his own childhood.

Now, Ahmad’s kids are among the first to be raised among AI ghosts. To continually enhance the family’s experience, their father continuously updates his father’s digital replica. Ahmad is currently most excited about recent audio advancements that make it easier to add a voice element. He hopes that within the next year, he might be able to use AI to finally nail down his South Asian father’s accent, which up to now has always sounded “just off.” For others working in this space, the next frontier is realistic video or even augmented reality tools, Ahmad told Ars.

To this day, the bot retains sentimental value for Ahmad, but, as Haneman suggested, the bot was not the only way he memorialized his dad. He also created a mosaic, and while his father never saw it, either, Ahmad thinks his dad would have approved.

“He would have been very happy,” Ahmad said.

There’s no way to predict how future generations may view grief tech. But while Ahmad said he’s not sure he’d be interested in an augmented reality interaction with his dad’s digital replica, kids raised seeing AI ghosts as a natural part of their lives may not be as hesitant to embrace or even build new features. Talking to Ars, Ahmad fondly remembered his young daughter once saw that he was feeling sad and came up with her own AI idea to help her dad feel better.

“It would be really nice if you can just take this program and we build a robot that looks like your dad, and then add it to the robot, and then you can go and hug the robot,” she said, according to her father’s memory.

How to draft a will to avoid becoming an AI ghost—it’s not easy Read More »