Toxic chemicals from Ohio train derailment lingered in buildings for months

Enlarge / This video screenshot released by the US National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB) shows the site of a derailed freight train in East Palestine, Ohio.

On February 3, 2023, a train carrying chemicals jumped the tracks in East Palestine, Ohio, rupturing railcars filled with hazardous materials and fueling chemical fires at the foothills of the Appalachian Mountains.

The disaster drew global attention as the governors of Ohio and Pennsylvania urged evacuations for a mile around the site. Flames and smoke billowed from burning chemicals, and an acrid odor radiated from the derailment area as chemicals entered the air and spilled into a nearby creek.

Three days later, at the urging of the rail company Norfolk Southern, about 1 million pounds of vinyl chloride, a chemical that can be toxic to humans at high doses, was released from the damaged train cars and set aflame.

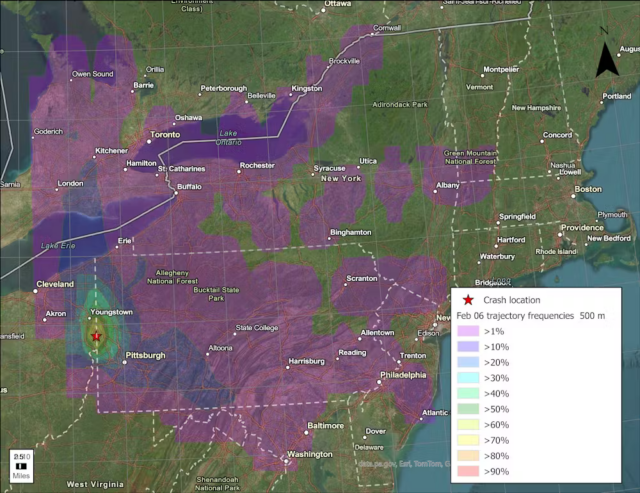

Federal investigators later concluded that the open burn and the black mushroom cloud it produced were unnecessary, but it was too late. Railcar chemicals spread into Ohio and Pennsylvania.

As environmental engineers, I and my colleagues are often asked to assist with public health decisions after disasters by government agencies and communities. After the evacuation order was lifted, community members asked for help.

In a new study, we describe the contamination we found, along with problems with the response and cleanup that, in some cases, increased the chances that people would be exposed to hazardous chemicals. It offers important lessons to better protect communities in the future.

How chemicals get into homes and water

When large amounts of chemicals are released into the environment, the air can become toxic. Chemicals can also wash into waterways and seep into the ground, contaminating groundwater and wells. Some chemicals can travel below ground into nearby buildings and make the indoor air unsafe.

Enlarge / A computer model shows how chemicals from the train may have spread, given wind patterns. The star on the Ohio-Pennsylvania line is the site of the derailment.

Air pollution can find its way into buildings through cracks, windows, doors, and other portals. Once inside, the chemicals can penetrate home items like carpets, drapes, furniture, counters, and clothing. When the air is stirred up, those chemicals can be released again.

Evacuation order lifted, but buildings were contaminated

Three weeks after the derailment, we began investigating the safety of the area near 17 buildings in Ohio and Pennsylvania. The highest concentration of air pollution occurred in the 1-mile evacuation zone and a shelter-in-place band another mile beyond that. But the chemical plume also traveled outside these areas.

In and outside East Palestine, evidence indicated that chemicals from the railcars had entered buildings. Many residents complained about headaches, rashes, and other health symptoms after reentering the buildings.

At one building 0.2 miles away from the derailment site, the indoor air was still contaminated more than four months later.

Nine days after the derailment, sophisticated air testing by a business owner showed the building’s indoor air was contaminated with butyl acrylate and other chemicals carried by the railcars. Butyl acrylate was found above the two-week exposure level, a level at which measures should be taken to protect human health.

When rail company contractors visited the building 11 days after the wreck, their team left after just 10 minutes. They reported an “overwhelming/unpleasent odor” even though their government-approved handheld air pollution detectors detected no chemicals. This building was located directly above Sulphur Run creek, which had been heavily contaminated by the spill. Chemicals likely entered from the initial smoke plumes and also rose from the creek into the building.

Our tests weeks later revealed that railcar chemicals had even penetrated the business’s silicone wristband products on its shelves. We also detected several other chemicals that may have been associated with the spill.

Enlarge / Homes and businesses were mere feet from the contaminated waterways in East Palestine.

Weeks after the derailment, government officials discovered that air in the East Palestine Municipal Building, about 0.7 miles away from the derailment site, was also contaminated. Airborne chemicals had entered that building through an open drain pipe from Sulphur Run.

More than a month after the evacuation order was lifted, the Ohio Environmental Protection Agency acknowledged that multiple buildings in East Palestine were being contaminated as contractors cleaned contaminated culverts under and alongside buildings. Chemicals were entering the buildings.

Toxic chemicals from Ohio train derailment lingered in buildings for months Read More »