Here’s the real reason Endurance sank

The ship wasn’t designed to withstand the powerful ice compression forces—and Shackleton knew it.

The Endurance, frozen and keeled over in the ice of the Weddell Sea. Credit: BF/Frank Hurley

In 1915, intrepid British explorer Sir Ernest Shackleton and his crew were stranded for months in the Antarctic after their ship, Endurance, was trapped by pack ice, eventually sinking into the freezing depths of the Weddell Sea. Miraculously, the entire crew survived. The prevailing popular narrative surrounding the famous voyage features two key assumptions: that Endurance was the strongest polar ship of its time, and that the ship ultimately sank after ice tore away the rudder.

However, a fresh analysis reveals that Endurance would have sunk even with an intact rudder; it was crushed by the cumulative compressive forces of the Antarctic ice with no single cause for the sinking. Furthermore, the ship wasn’t designed to withstand those forces, and Shackleton was likely well aware of that fact, according to a new paper published in the journal Polar Record. Yet he chose to embark on the risky voyage anyway.

Author Jukka Tuhkuri of Aalto University is a polar explorer and one of the leading researchers on ice worldwide. He was among the scientists on the Endurance22 mission that discovered the Endurance shipwreck in 2022, documented in a 2024 National Geographic documentary. The ship was in pristine condition partly because of the lack of wood-eating microbes in those waters. In fact, the Endurance22 expedition’s exploration director, Mensun Bound, told The New York Times at the time that the shipwreck was the finest example he’s ever seen; Endurance was “in a brilliant state of preservation.”

As previously reported, Endurance set sail from Plymouth on August 6, 1914, with Shackleton joining his crew in Buenos Aires, Argentina. By the time they reached the Weddell Sea in January 1915, accumulating pack ice and strong gales slowed progress to a crawl. Endurance became completely icebound on January 24, and by mid-February, Shackleton ordered the boilers to be shut off so that the ship would drift with the ice until the weather warmed sufficiently for the pack to break up. It would be a long wait. For 10 months, the crew endured the freezing conditions. In August, ice floes pressed into the ship with such force that the ship’s decks buckled.

The ship’s structure nonetheless remained intact, but by October 25, Shackleton realized Endurance was doomed. He and his men opted to camp out on the ice some two miles (3.2 km) away, taking as many supplies as they could with them. Compacted ice and snow continued to fill the ship until a pressure wave hit on November 13, crushing the bow and splitting the main mast—all of which was captured on camera by crew photographer Frank Hurley. Another pressure wave hit in the late afternoon on November 21, lifting the ship’s stern. The ice floes parted just long enough for Endurance to finally sink into the ocean before closing again to erase any trace of the wreckage.

Once the wreck had been found, the team recorded as much as they could with high-resolution cameras and other instruments. Vasarhelyi, particularly, noted the technical challenge of deploying a remote digital 4K camera with lighting at 9,800 feet underwater, and the first deployment at that depth of photogrammetric and laser technology. This resulted in a millimeter-scale digital reconstruction of the entire shipwreck to enable close study of the finer details.

Challenging the narrative

The ice and wave tank at Aalto University. Credit: Aalto University

It was shortly after the Endurance22 mission found the shipwreck that Tuhkuri realized that there had never been a thorough structural analysis conducted of the vessel to confirm the popular narrative. Was Endurance truly the strongest polar ship of that time, and was a broken rudder the actual cause of the sinking? He set about conducting his own investigation to find out, analyzing Shackleton’s diaries and personal correspondence, as well as the diaries and correspondence of several Endurance crew members.

Tuhkuri also conducted a naval architectural analysis of the vessel under the conditions of compressive ice, which had never been done before. He then compared those results with the underwater images of the Endurance shipwreck. He also looked at comparable wooden polar expedition ships and steel icebreakers built in the late 1800s and early 1900s.

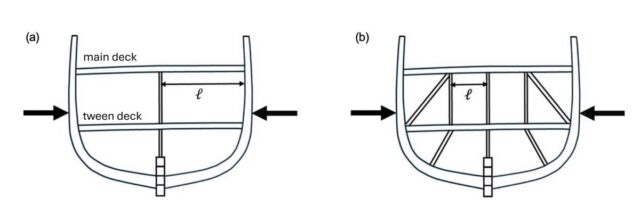

Endurance was originally named Polaris; Shackleton renamed it when he purchased the ship in 1914 for his doomed expedition. Per Tuhkuri, the ship had a lower (tween) deck, a main deck, and a short bridge deck above them that stopped at the machine room in order to make space for the steam engine and boiler. There were no beams in the machine room area, nor any reinforcing diagonal beams, which weakened this significant part of the ship’s hull.

This is because Endurance was originally built for polar tourism and for hunting polar bears and walruses in the Arctic; at the ice edge, ships only needed sufficiently strong planking and frames to withstand the occasional collision from ice floes. However, “In pack ice conditions, where compression from the ice needs to be taken into account, deck beams become of key importance,” Tuhkuri wrote. “It is the deck beams that keep the two ship sides apart and maintain the shape of a ship. Without strong enough deck beams, a vessel gets crushed by compressive ice, more or less irrespective of the thickness of planking and frames.”

The Endurance was nonetheless sturdy enough to withstand five serious ice compression events before her final sinking. On April 4, 1915, one of the scientists on board reported hearing loud rumbling noises from a 3-meter-high ice ridge that formed near the ship, causing the ship to vibrate. Tuhkuri believes this was due to a “compressive failure process” as ice crushed against the hull. On July 14, a violent snowstorm hit, and crew members could hear the ice breaking beneath the ship. The ice ridges that formed over the next few days were sufficiently concerning that Shackleton instituted four-hour watches on deck and insisted on having everything packed in case they had to abandon ship.

Crushed by the ice

Idealized cross sections of early Antarctic ships. Endurance was type (a); Deutschland was type (b). Credit: J. Tuhkuri, 2025

On August 1, an ice floe fractured and grinding noises were heard beneath the ship as the floe piled underneath it, lifting Endurance and causing her to first heel starboard and then heel to port, as several deck beams began to buckle. Similar compression events kept happening until there was a sudden escalation on September 30. The hull began vibrating hard enough to shake the whole rigging as even more ice crushed against the hull. Even the linoleum on the floors buckled; Harry McNish wrote in his diary that it looked like Endurance “was going to pieces.”

Yet another ice compression event occurred on October 17, pushing the vessel one meter into the air as the iron plates on the engine room’s floor buckled and slid over each other. Ship scientist Reginald James wrote that “for a time things were not good as the pressure was mostly along the region of the engine room where there are no beams of any strength,” while Captain Worsley described the engine room as “the weakest part of the ship.”

By the afternoon, Endurance was heeled almost 30 degrees to port, so much so that the keel was visible from the starboard side, per Tuhkuri, although the ice started to fracture in the evening so that the ship could shift upright again. The crew finally abandoned ship on October 27 after an even more severe compression event hit a few days before. Endurance finally sank below the ice on November 21.

Tuhkuri’s analysis of the structural damage to Endurance revealed that the rudder and the stern post were indeed torn off, confirmed by crew correspondence and diaries and by the underwater images taken of the wreck. The keel was also ripped off, with McNish noting in his diary that the ship broke into two halves as a result. The underwater images are less clear on this point, but Tuhkuri writes that there is something “some distance forward from the rudder, on the port side” that “could be the end of a displaced part of the keel sticking up from under the ship.”

All the diaries mentioned the buckling and breaking of deck beams, and there was much structural damage to the ship’s sides; for instance, Worsley writes of “great spikes of ice… forcing their way through the ship’s sides.” There are no visible holes in the wreck’s sides in the underwater images, but Tuhkuri posits that the damage is likely buried in the mud on the sea bed, given that by late October, Endurance “was heavily listed and the bottom was exposed.”

Jukka Tuhkuri on the ice. Credit: Aalto University

Based on his analysis, Tuhkuri concluded that the rudder wasn’t the sole or primary reason for the ship’s sinking. “Endurance would have sunk even if it did not have a rudder at all,” Tuhkuri wrote; it was crushed by the ice, with no single reason for its eventual sinking. Shackleton himself described the process as ice floes “simply annihilating the ship.”

Perhaps the most surprising finding is that Shackleton knew of Endurance‘s structural shortcomings even before undertaking the voyage. Per Tuhkuri, the devastating effects of compressive ice on ships were known to shipbuilders in the early 1900s. An early Swedish expedition was forced to abandon its ship Antarctic in February 1903 when it became trapped in the ice. Things progressed much like Endurance: the ice lifted Antarctic up so that the ship heeled over, with ice-crushed sides, buckling beams, broken planking, and a damaged rudder and stern post. The final sinking occurred when an advancing ice floe ripped off the keel.

Shackleton knew of Antarctic‘s fate and had even been involved in the rescue operation. He also helped Wilhelm Filchner make final preparations for Filchner’s 1911–1913 polar expedition with a ship named Deutschland; he even advised his colleague to strengthen the ship’s hull by adding diagonal beams, the better to withstand the Weddell Sea ice. Filchner did so, and as a result, Deutschland survived eight months of being trapped in compressive ice until the ship was finally able to break free and sail home. (It took a torpedo attack in 1917 to sink the good ship Deutschland.)

The same shipyard that modified Deutschland had also just signed a contract to build Endurance (then called Polaris). So both Shackleton and the shipbuilders knew how destructive compressive ice could be and how to bolster a ship against it. Yet Endurance was not outfitted with diagonal beams to strengthen its hull. And knowing this, Shackleton bought Endurance anyway for his 1914–1915 voyage. In a 1914 letter to his wife, he even compared the strength of its construction unfavorably with that of the Nimrod, the ship he used for his 1907–1909 expedition. So Shackleton had to know he was taking a big risk.

“Even simple structural analysis shows that the ship was not designed for the compressive pack ice conditions that eventually sank it,” said Tuhkuri. “The danger of moving ice and compressive loads—and how to design a ship for such conditions—was well understood before the ship sailed south. So we really have to wonder why Shackleton chose a vessel that was not strengthened for compressive ice. We can speculate about financial pressures or time constraints, but the truth is, we may never know. At least we now have more concrete findings to flesh out the stories.”

Polar Record, 2025. DOI: 10.1017/S0032247425100090 (About DOIs).

Jennifer is a senior writer at Ars Technica with a particular focus on where science meets culture, covering everything from physics and related interdisciplinary topics to her favorite films and TV series. Jennifer lives in Baltimore with her spouse, physicist Sean M. Carroll, and their two cats, Ariel and Caliban.

Here’s the real reason Endurance sank Read More »