The NPU in your phone keeps improving—why isn’t that making AI better?

Almost every technological innovation of the past several years has been laser-focused on one thing: generative AI. Many of these supposedly revolutionary systems run on big, expensive servers in a data center somewhere, but at the same time, chipmakers are crowing about the power of the neural processing units (NPU) they have brought to consumer devices. Every few months, it’s the same thing: This new NPU is 30 or 40 percent faster than the last one. That’s supposed to let you do something important, but no one really gets around to explaining what that is.

Experts envision a future of secure, personal AI tools with on-device intelligence, but does that match the reality of the AI boom? AI on the “edge” sounds great, but almost every AI tool of consequence is running in the cloud. So what’s that chip in your phone even doing?

What is an NPU?

Companies launching a new product often get bogged down in superlatives and vague marketing speak, so they do a poor job of explaining technical details. It’s not clear to most people buying a phone why they need the hardware to run AI workloads, and the supposed benefits are largely theoretical.

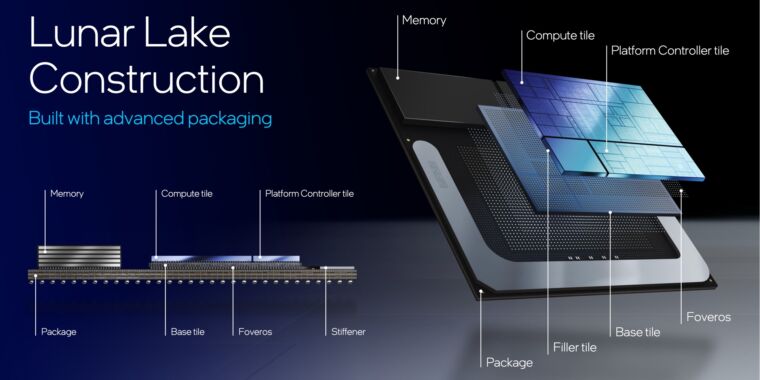

Many of today’s flagship consumer processors are systems-on-a-chip (SoC) because they incorporate multiple computing elements—like CPU cores, GPUs, and imaging controllers—on a single piece of silicon. This is true of mobile parts like Qualcomm’s Snapdragon or Google’s Tensor, as well as PC components like the Intel Core Ultra.

The NPU is a newer addition to chips, but it didn’t just appear one day—there’s a lineage that brought us here. NPUs are good at what they do because they emphasize parallel computing, something that’s also important in other SoC components.

Qualcomm devotes significant time during its new product unveilings to talk about its Hexagon NPUs. Keen observers may recall that this branding has been reused from the company’s line of digital signal processors (DSPs), and there’s a good reason for that.

“Our journey into AI processing started probably 15 or 20 years ago, wherein our first anchor point was looking at signal processing,” said Vinesh Sukumar, Qualcomm’s head of AI products. DSPs have a similar architecture compared to NPUs, but they’re much simpler, with a focus on processing audio (e.g., speech recognition) and modem signals.

The NPU is one of multiple components in modern SoCs. Credit: Qualcomm

As the collection of technologies we refer to as “artificial intelligence” developed, engineers began using DSPs for more types of parallel processing, like long short-term memory (LSTM). Sukumar explained that as the industry became enamored with convolutional neural networks (CNNs), the technology underlying applications like computer vision, DSPs became focused on matrix functions, which are essential to generative AI processing as well.

While there is an architectural lineage here, it’s not quite right to say NPUs are just fancy DSPs. “If you talk about DSPs in the general term of the word, yes, [an NPU] is a digital signal processor,” said MediaTek Assistant Vice President Mark Odani. “But it’s all come a long way and it’s a lot more optimized for parallelism, how the transformers work, and holding huge numbers of parameters for processing.”

Despite being so prominent in new chips, NPUs are not strictly necessary for running AI workloads on the “edge,” a term that differentiates local AI processing from cloud-based systems. CPUs are slower than NPUs but can handle some light workloads without using as much power. Meanwhile, GPUs can often chew through more data than an NPU, but they use more power to do it. And there are times you may want to do that, according to Qualcomm’s Sukumar. For example, running AI workloads while a game is running could favor the GPU.

“Here, your measurement of success is that you cannot drop your frame rate while maintaining the spatial resolution, the dynamic range of the pixel, and also being able to provide AI recommendations for the player within that space,” says Sukumar. “In this kind of use case, it actually makes sense to run that in the graphics engine, because then you don’t have to keep shifting between the graphics and a domain-specific AI engine like an NPU.”

Livin’ on the edge is hard

Unfortunately, the NPUs in many devices sit idle (and not just during gaming). The mix of local versus cloud AI tools favors the latter because that’s the natural habitat of LLMs. AI models are trained and fine-tuned on powerful servers, and that’s where they run best.

A server-based AI, like the full-fat versions of Gemini and ChatGPT, is not resource-constrained like a model running on your phone’s NPU. Consider the latest version of Google’s on-device Gemini Nano model, which has a context window of 32k tokens. That is a more than 2x improvement over the last version. However, the cloud-based Gemini models have context windows of up to 1 million tokens, meaning they can process much larger volumes of data.

Both cloud-based and edge AI hardware will continue getting better, but the balance may not shift in the NPU’s favor. “The cloud will always have more compute resources versus a mobile device,” said Google’s Shenaz Zack, senior product manager on the Pixel team.

“If you want the most accurate models or the most brute force models, that all has to be done in the cloud,” Odani said. “But what we’re finding is that, in a lot of the use cases where there’s just summarizing some text or you’re talking to your voice assistant, a lot of those things can fit within three billion parameters.”

Squeezing AI models onto a phone or laptop involves some compromise—for example, by reducing the parameters included in the model. Odani explained that cloud-based models run hundreds of billions of parameters, the weighting that determines how a model processes input tokens to generate outputs. You can’t run anything like that on a consumer device right now, so developers have to vastly scale back the size of models for the edge. Odani says MediaTek’s latest ninth-generation NPU can handle about 3 billion parameters—a difference of several orders of magnitude.

The amount of memory available in a phone or laptop is also a limiting factor, so mobile-optimized AI models are usually quantized. That means the model’s estimation of the next token runs with less precision. Let’s say you want to run one of the larger open models, like Llama or Gemma 7b, on your device. The de facto standard is FP16, known as half-precision. At that level, a model with 7 billion parameters will lock up 13 or 14 gigabytes of memory. Stepping down to FP4 (quarter-precision) brings the size of the model in memory to a few gigs.

“When you compress to, let’s say, between three and four gigabytes, it’s a sweet spot for integration into memory constrained form factors like a smartphone,” Sukumar said. “And there’s been a lot of investment in the ecosystem and at Qualcomm to look at various ways of compressing the models without losing quality.”

It’s difficult to create a generalized AI with these limitations for mobile devices, but computers—and especially smartphones—are a wellspring of data that can be pumped into models to generate supposedly helpful outputs. That’s why most edge AI is geared toward specific, narrow use cases, like analyzing screenshots or suggesting calendar appointments. Google says its latest Pixel phones run more than 100 AI models, both generative and traditional.

Even AI skeptics can recognize that the landscape is changing quickly. In the time it takes to shrink and optimize AI models for a phone or laptop, new cloud models may appear that make that work obsolete. This is also why third-party developers have been slow to utilize NPU processing in apps. They either have to plug into an existing on-device model, which involves restrictions and rapidly moving development targets, or deploy their own custom models. Neither is a great option currently.

A matter of trust

If the cloud is faster and easier, why go to the trouble of optimizing for the edge and burning more power with an NPU? Leaning on the cloud means accepting a level of dependence and trust in the people operating AI data centers that may not always be appropriate.

“We always start off with user privacy as an element,” said Qualcomm’s Sukumar. He explained that the best inference is not general in nature—it’s personalized based on the user’s interests and what’s happening in their lives. Fine-tuning models to deliver that experience calls for personal data, and it’s safer to store and process that data locally.

Even when companies say the right things about privacy in their cloud services, they’re far from guarantees. The helpful, friendly vibe of general chatbots also encourages people to divulge a lot of personal information, and if that assistant is running in the cloud, your data is there as well. OpenAI’s copyright fight with The New York Times could lead to millions of private chats being handed over to the publisher. The explosive growth and uncertain regulatory framework of gen AI make it hard to know what’s going to happen to your data.

“People are using a lot of these generative AI assistants like a therapist,” Odani said. “And you don’t know one day if all this stuff is going to come out on the Internet.”

Not everyone is so concerned. Zack claims Google has built “the world’s most secure cloud infrastructure,” allowing it to process data where it delivers the best results. Zack uses Video Boost and Pixel Studio as examples of this approach, noting that Google’s cloud is the only way to make these experiences fast and high-quality. The company recently announced its new Private AI Compute system, which it claims is just as safe as local AI.

Even if that’s true, the edge has other advantages—edge AI is just more reliable than a cloud service. “On-device is fast,” Odani said. “Sometimes I’m talking to ChatGPT and my Wi-Fi goes out or whatever, and it skips a beat.”

The services hosting cloud-based AI models aren’t just a single website—the Internet of today is massively interdependent, with content delivery networks, DNS providers, hosting, and other services that could degrade or shut down your favorite AI in the event of a glitch. When Cloudflare suffered a self-inflicted outage recently, ChatGPT users were annoyed to find their trusty chatbot was unavailable. Local AI features don’t have that drawback.

Cloud dominance

Everyone seems to agree that a hybrid approach is necessary to deliver truly useful AI features (assuming those exist), sending data to more powerful cloud services when necessary—Google, Apple, and every other phone maker does this. But the pursuit of a seamless experience can also obscure what’s happening with your data. More often than not, the AI features on your phone aren’t running in a secure, local way, even when the device has the hardware to do that.

Take, for example, the new OnePlus 15. This phone has Qualcomm’s brand-new Snapdragon 8 Elite Gen 5, which has an NPU that is 37 percent faster than the last one, for whatever that’s worth. Even with all that on-device AI might, OnePlus is heavily reliant on the cloud to analyze your personal data. Features like AI Writer and the AI Recorder connect to the company’s servers for processing, a system OnePlus assures us is totally safe and private.

Similarly, Motorola released a new line of foldable Razr phones over the summer that are loaded with AI features from multiple providers. These phones can summarize your notifications using AI, but you might be surprised how much of it happens in the cloud unless you read the terms and conditions. If you buy the Razr Ultra, that summarization happens on your phone. However, the cheaper models with less RAM and NPU power use cloud services to process your notifications. Again, Motorola says this system is secure, but a more secure option would have been to re-optimize the model for its cheaper phones.

Even when an OEM focuses on using the NPU hardware, the results can be lacking. Look at Google’s Daily Hub and Samsung’s Now Brief. These features are supposed to chew through all the data on your phone and generate useful recommendations and actions, but they rarely do anything aside from showing calendar events. In fact, Google has temporarily removed Daily Hub from Pixels because the feature did so little, and Google is a pioneer in local AI with Gemini Nano. Google has actually moved some parts of its mobile AI experience from local to cloud-based processing in recent months.

Those “brute force” models appear to be winning, and it doesn’t hurt that companies also get more data when you interact with their private computing cloud services.

Maybe take what you can get?

There’s plenty of interest in local AI, but so far, that hasn’t translated to an AI revolution in your pocket. Most of the AI advances we’ve seen so far depend on the ever-increasing scale of cloud systems and the generalized models that run there. Industry experts say that extensive work is happening behind the scenes to shrink AI models to work on phones and laptops, but it will take time for that to make an impact.

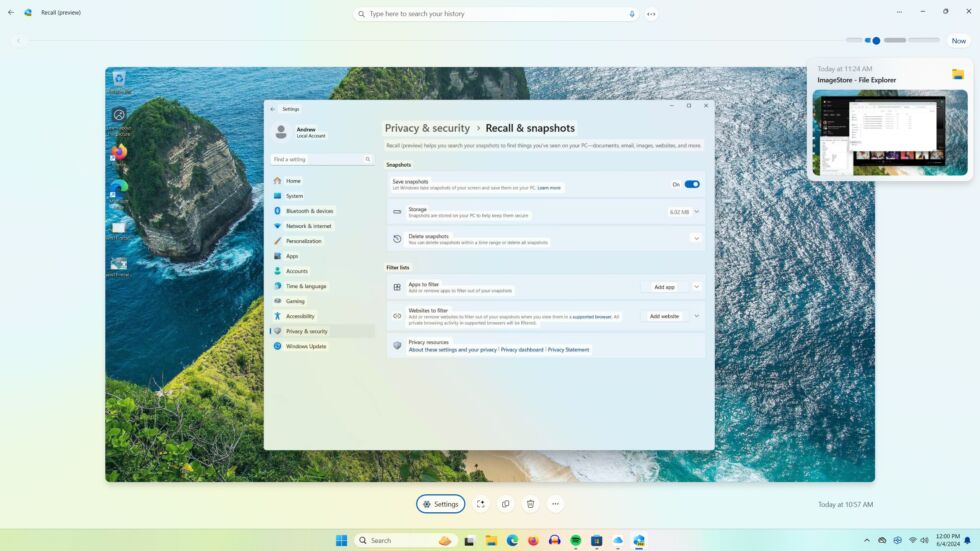

In the meantime, local AI processing is out there in a limited way. Google still makes use of the Tensor NPU to handle sensitive data for features like Magic Cue, and Samsung really makes the most of Qualcomm’s AI-focused chipsets. While Now Brief is of questionable utility, Samsung is cognizant of how reliance on the cloud may impact users, offering a toggle in the system settings that restricts AI processing to run only on the device. This limits the number of available AI features, and others don’t work as well, but you’ll know none of your personal data is being shared. No one else offers this option on a smartphone.

Samsung offers an easy toggle to disable cloud AI and run all workloads on-device. Credit: Ryan Whitwam

Samsung spokesperson Elise Sembach said the company’s AI efforts are grounded in enhancing experiences while maintaining user control. “The on-device processing toggle in One UI reflects this approach. It gives users the option to process AI tasks locally for faster performance, added privacy, and reliability even without a network connection,” Sembach said.

Interest in edge AI might be a good thing even if you don’t use it. Planning for this AI-rich future can encourage device makers to invest in better hardware—like more memory to run all those theoretical AI models.

“We definitely recommend our partners increase their RAM capacity,” said Sukumar. Indeed, Google, Samsung, and others have boosted memory capacity in large part to support on-device AI. Even if the cloud is winning, we’ll take the extra RAM.

Ryan Whitwam is a senior technology reporter at Ars Technica, covering the ways Google, AI, and mobile technology continue to change the world. Over his 20-year career, he’s written for Android Police, ExtremeTech, Wirecutter, NY Times, and more. He has reviewed more phones than most people will ever own. You can follow him on Bluesky, where you will see photos of his dozens of mechanical keyboards.

The NPU in your phone keeps improving—why isn’t that making AI better? Read More »