Dogs came in a wide range of sizes and shapes long before modern breeds

“The concept of ‘breed’ is very recent and does not apply to the archaeological record,” Evin said. People have, of course, been breeding dogs for particular traits for as long as we’ve had dogs, and tiny lap dogs existed even in ancient Rome. However, it’s unlikely that a Neolithic herder would have described his dog as being a distinct “breed” from his neighbor’s hunting partner, even if they looked quite different. Which, apparently, they did.

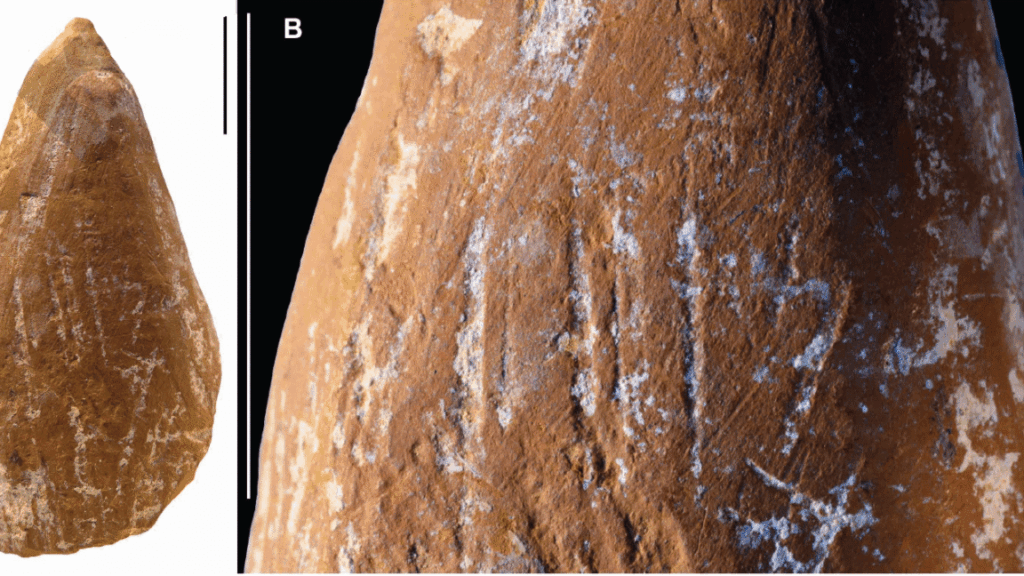

Dogs had about half of their modern diversity (at least in skull shapes and sizes) by the Neolithic. Credit: Kiona Smith

Bones only tell part of the story

“We know from genetic models that domestication should have started during the late Pleistocene,” Evin told Ars. A 2021 study suggested that domestic dogs have been a separate species from wolves for more than 23,000 years. But it took a while for differences to build up.

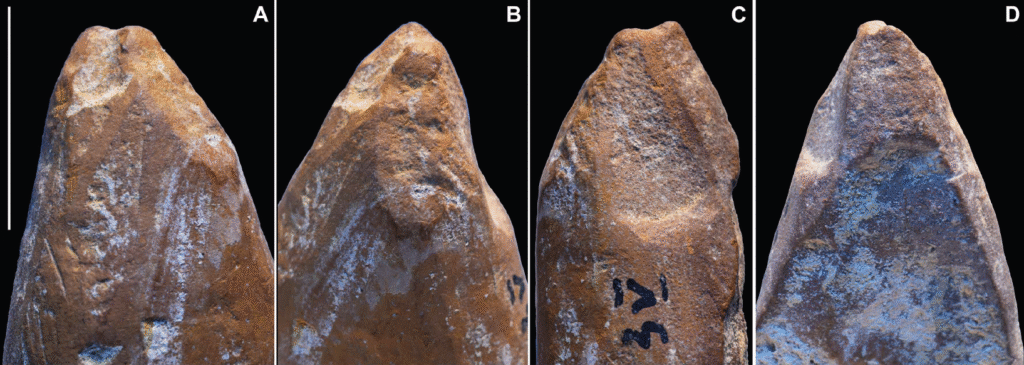

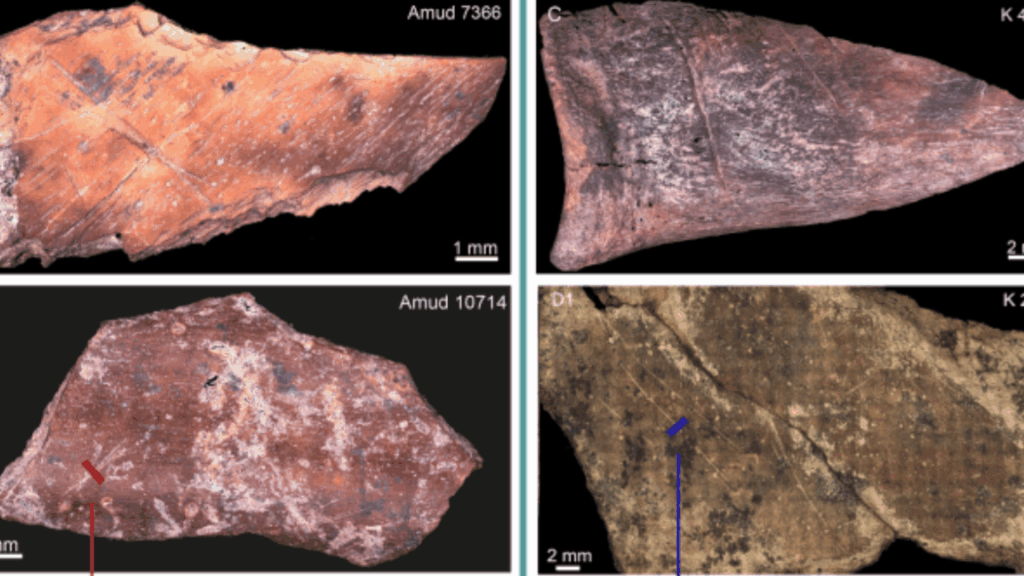

Evin and her colleagues had access to 17 canine skulls that ranged from 12,700 to 50,000 years old—prior to the end of the ice age—and they all looked enough like modern wolves that, as Evin put it, “for now, we have no evidence to suggest that any of the wolf-like skulls did not belong to wolves or looked different from them.” In other words, if you’re just looking at the skull, it’s hard to tell the earliest dogs from wild wolves.

We have no way to know, of course, what the living dog might have looked like. It’s worth mentioning that Evin and her colleagues found a modern Saint Bernard’s skull that, according to their statistical analysis, looked more wolf-like than dog-like. But even if it’s not offering you a brandy keg, there’s no mistaking a live Saint Bernard, with its droopy jowls and floppy ears, for a wolf.

“Skull shape tells us a lot about function and evolutionary history, but it represents only one aspect of the animal’s appearance. This means that two dogs with very similar skulls could have looked quite different in life,” Evin told Ars. “It’s an important reminder that the archaeological record captures just part of the biological and cultural story.”

And with only bones—and sparse ones, at that—to go on, we may be missing some of the early chapters of dogs’ biological and cultural story. Domestication tends to select the friendliest animals to produce the next generation, and apparently that comes with a particular set of evolutionary side effects, whether you’re studying wolves, foxes, cattle, or pigs. Spots, floppy ears, and curved tails all seem to be part of the genetic package that comes with inter-species friendliness. But none of those traits is visible in the skull.

Dogs came in a wide range of sizes and shapes long before modern breeds Read More »