NASA lays out how SpaceX will refuel Starships in low-Earth orbit

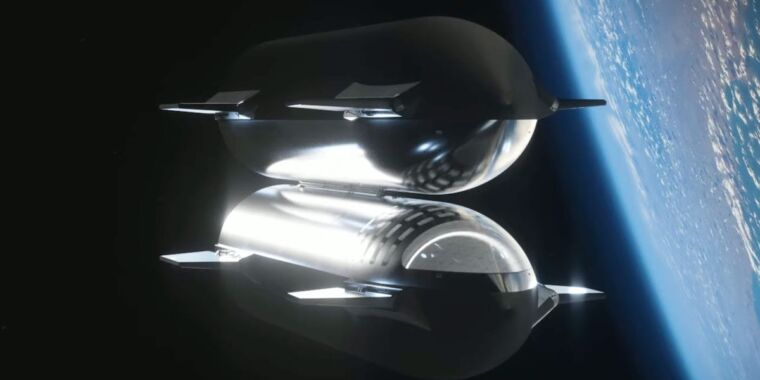

Enlarge / Artist’s illustration of two Starships docked belly-to-belly in orbit.

SpaceX

Some time next year, NASA believes SpaceX will be ready to link two Starships in orbit for an ambitious refueling demonstration, a technical feat that will put the Moon within reach.

SpaceX is under contract with NASA to supply two human-rated Starships for the first two astronaut landings on the Moon through the agency’s Artemis program, which aims to return people to the lunar surface for the first time since 1972. The first of these landings, on NASA’s Artemis III mission, is currently targeted for 2026, although this is widely viewed as an ambitious schedule.

Last year, NASA awarded a contract to Blue Origin to develop its own human-rated Blue Moon lunar lander, giving Artemis managers two options for follow-on missions.

Designers of both landers were future-minded. They designed Starship and Blue Moon for refueling in space. This means they can eventually be reused for multiple missions, and ultimately, could take advantage of propellants produced from resources on the Moon or Mars.

Amit Kshatriya, who leads the “Moon to Mars” program within NASA’s exploration division, outlined SpaceX’s plan to do this in a meeting with a committee of the NASA Advisory Council on Friday. He said the Starship test program is gaining momentum, with the next test flight from SpaceX’s Starbase launch site in South Texas expected by the end of May.

“Production is not the issue,” Kshatriya said. “They’re rolling cores out. The engines are flowing into the factory. That is not the issue. The issue is it is a significant development challenge to do what they’re trying to do … We have to get on top of this propellant transfer problem. It is the right problem to try and solve. We’re trying to build a blueprint for deep space exploration.”

Road map to refueling

Before getting to the Moon, SpaceX and Blue Origin must master the technologies and techniques required for in-space refueling. Right now, SpaceX is scheduled to attempt the first demonstration of a large-scale propellant transfer between two Starships in orbit next year.

There will be at least several more Starship test flights before then. During the most recent Starship test flight in March, SpaceX conducted a cryogenic propellant transfer test between two tanks inside the vehicle. This tank-to-tank transfer of liquid oxygen was part of a demonstration supported with NASA funding. Agency officials said this demonstration would allow engineers to learn more about how the fluid behaves in a low-gravity environment.

Kshatriya said that while engineers are still analyzing the results of the cryogenic transfer demonstration, the test on the March Starship flight “was successful by all accounts.”

“That milestone is behind them,” he said Friday. Now, SpaceX will move out with more Starship test flights. The next launch will try to check off a few more capabilities SpaceX didn’t demonstrate on the March test flight.

These will include a precise landing of Starship’s Super Heavy booster in the Gulf of Mexico, which is necessary before SpaceX tries to land the booster back at its launch pad in Texas. Another objective will likely be the restart of a single Raptor engine on Starship in flight, which SpaceX didn’t accomplish on the March flight due to unexpected roll rates on the vehicle as it coasted through space. Achieving an in-orbit engine restart—necessary to guide Starship toward a controlled reentry—is a prerequisite for future launches into a stable higher orbit, where the ship could loiter for hours, days, or weeks to deploy satellites and attempt refueling.

In the long run, SpaceX wants to ramp up the Starship launch cadence to many daily flights from multiple launch sites. To achieve that goal, SpaceX plans to recover and rapidly reuse Starships and Super Heavy boosters, building on expertise from the partially reusable Falcon 9 rocket. Elon Musk, SpaceX’s founder and CEO, is keen on reusing ships and boosters as soon as possible. Earlier this month, Musk said he is optimistic SpaceX can recover a Super Heavy booster in Texas later this year and land a Starship back in Texas sometime next year.

NASA lays out how SpaceX will refuel Starships in low-Earth orbit Read More »