Rocket Report: Canada invests in sovereign launch; India flexes rocket muscles

Europe’s Ariane 6 rocket gave an environmental monitoring satellite a perfect ride to space.

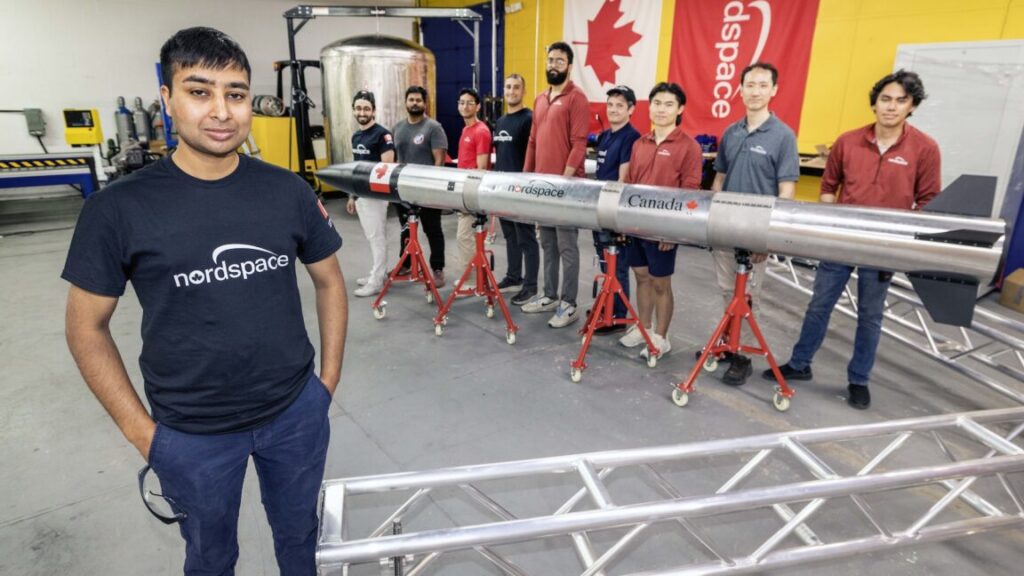

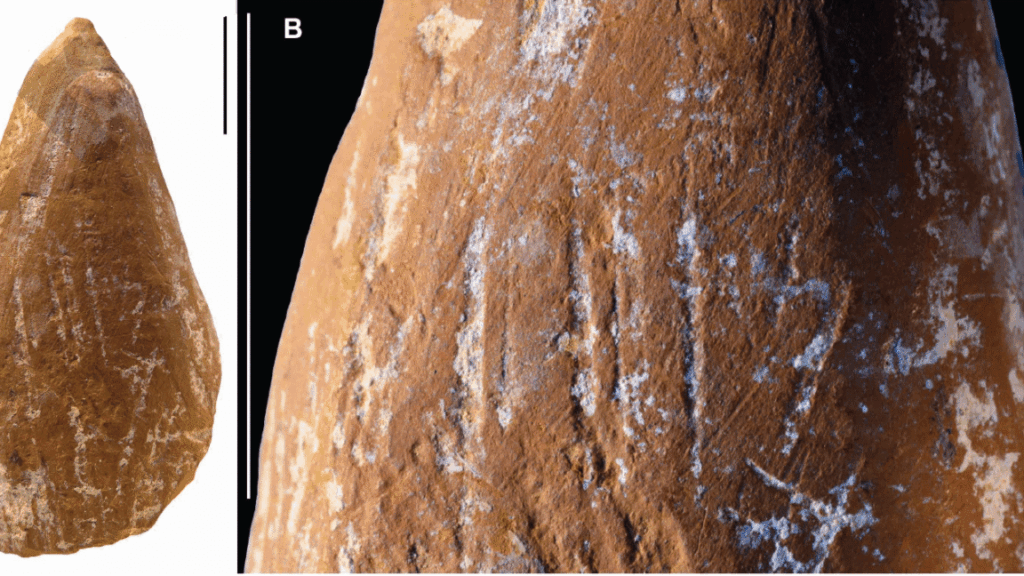

Rahul Goel, the CEO of Canadian launch startup NordSpace, poses with a suborbital demo rocket and members of his team in Toronto earlier this year. Credit: Andrew Francis Wallace/Toronto Star via Getty Images

Welcome to Edition 8.18 of the Rocket Report! NASA is getting a heck of a deal from Blue Origin for launching the agency’s ESCAPADE mission to Mars. Blue Origin is charging NASA about $20 million for the launch on the company’s heavy-lift New Glenn rocket. A dedicated ride on any other rocket capable of the job would undoubtedly cost more.

But there are trade-offs. First, there’s the question of risk. The New Glenn rocket is only making its second flight, and it hasn’t been certified by NASA or the US Space Force. Second, the schedule for ESCAPADE’s launch has been at the whim of Blue Origin, which has delayed the mission several times due to issues developing New Glenn. NASA’s interplanetary missions typically have a fixed launch period, and the agency pays providers like SpaceX and United Launch Alliance a premium to ensure the launch happens when it needs to happen.

New Glenn is ready, the satellites are ready, and Blue Origin has set a launch date for Sunday, November 9. The mission will depart Earth outside of the usual interplanetary launch window, so orbital dynamics wizards came up with a unique trajectory that will get the satellites to Mars in 2027.

As always, we welcome reader submissions. If you don’t want to miss an issue, please subscribe using the box below (the form will not appear on AMP-enabled versions of the site). Each report will include information on small-, medium-, and heavy-lift rockets, as well as a quick look ahead at the next three launches on the calendar.

Canadian government backs launcher development. The federal budget released by the Liberal Party-led government of Canada this week includes a raft of new defense initiatives, including 182.6 million Canadian dollars ($129.4 million) for sovereign space launch capability, SpaceQ reports. The new funding is meant to “establish a sovereign space launch capability” with funds available this fiscal year and spent over three years. How the money will be spent and on what has yet to be released. As anticipated, Canada will have a new Defense Investment Agency (DIA) to oversee defense procurement. Overall, the government outlined 81.8 billion Canadian dollars ($58 billion) over five years for the Canadian Armed Forces. The Department of National Defense will manage the government’s cash infusion for sovereign launch capability.

Kick-starting an industry … Canada joins a growing list of nations pursuing homegrown launchers as many governments see access to space as key to national security and an opportunity for economic growth. International governments don’t want to be beholden to a small number of foreign launch providers from established space powers. That’s why startups in Germany, the United Kingdom, South Korea, and Australia are making a play in the launch arena, often with government support. A handful of Canadian startups, such as Maritime Launch Services, Reaction Dynamics, and NordSpace, are working on commercial satellite launchers. The Canadian government’s announcement came days after MDA Space, the largest established space company in Canada, announced its own multimillion-dollar investment in Maritime Launch Services.

The easiest way to keep up with Eric Berger’s and Stephen Clark’s reporting on all things space is to sign up for our newsletter. We’ll collect their stories and deliver them straight to your inbox.

Money alone won’t solve Europe’s space access woes. Increasing tensions with Russia have prompted defense spending boosts throughout Europe that will benefit fledgling smallsat launcher companies across the continent. But Europe is still years away from meeting its own space access needs, Space News reports. Space News spoke with industry analysts from two European consulting firms. They concluded that a lack of experience, not a deficit of money, is holding European launch startups back. None of the new crop of European rocket companies have completed a successful orbital flight.

Swimming in cash … The German company Isar Aerospace has raised approximately $600 million, the most funding of any of the European launch startups. Isar is also the only one of the bunch to make an orbital launch attempt. Its Spectrum rocket failed less than 30 seconds after liftoff last March, and a second launch is expected next year. Isar has attracted more investment than Rocket Lab, Firefly Aerospace, and Astra collectively raised on the private market before each of them successfully launched a rocket into orbit. In addition to Isar, several other European companies have raised more than $100 million on the road to developing a small satellite launcher. (submitted by EllPeaTea)

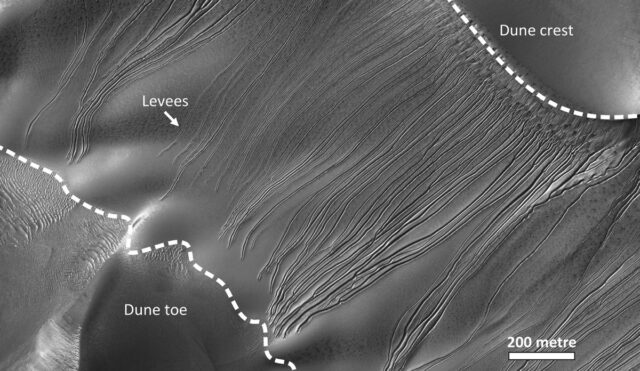

Successful ICBM test from Vandenberg. Air Force Global Strike Command tested an unarmed Minuteman III intercontinental ballistic missile in the predawn hours of Wednesday, Air and Space Forces Magazine reports. The test, the latest in a series of launches that have been carried out at regular intervals for decades, came as Russian President Vladimir Putin has touted the development of two new nuclear weapons and President Donald Trump has suggested in recent days that the US might resume nuclear testing. The ICBM launched from an underground silo at Vandenberg Space Force Base, California, and traveled some 4,200 miles to a test range in the Pacific Ocean after receiving launch orders from an airborne nuclear command-and-control plane.

Rehearsing for the unthinkable … The test, known as Glory Trip 254 (GT 254), provided a “comprehensive assessment” of the Minuteman III’s readiness to launch at a moment’s notice, according to the Air Force. “The data collected during the test is invaluable in ensuring the continued reliability and accuracy of the ICBM weapon system,” said Lt. Col. Karrie Wray, commander of the 576th Flight Test Squadron. For Minuteman III tests, the Air Force pulls its missiles from the fleet of some 400 operational ICBMs. This week’s test used one from F.E. Warren Air Force Base, Wyoming, and the missile was equipped with a single unarmed reentry vehicle that carried telemetry instrumentation instead of a warhead, service officials said. (submitted by EllPeaTea)

One crew launches, another may be stranded. Three astronauts launched to China’s Tiangong space station on October 31 and arrived at the outpost a few hours later, extending the station’s four-year streak of continuous crew operations. The Shenzhou 21 crew spacecraft lifted off on a Chinese Long March 2F rocket from the Jiuquan space center in the Gobi Desert. Shenzhou 21 is supposed to replace a three-man crew that has been on the Tiangong station since April, but China’s Manned Space Agency announced Tuesday the outgoing crew’s return craft may have been damaged by space junk, Ars reports.

Few details … Chinese officials said the Shenzhou 20 spacecraft will remain at the station while engineers investigate the potential damage. As of Thursday, China has not set a new landing date or declared whether the spacecraft is safe to return to Earth at all. “The Shenzhou 20 manned spacecraft is suspected of being impacted by small space debris,” Chinese officials wrote on social media. “Impact analysis and risk assessment are underway. To ensure the safety and health of the astronauts and the complete success of the mission, it has been decided that the Shenzhou 20 return mission, originally scheduled for November 5, will be postponed.” In the event Shenzhou 20 is unsafe to return, China could launch a rescue craft—Shenzhou 22—already on standby at the Jiuquan space center.

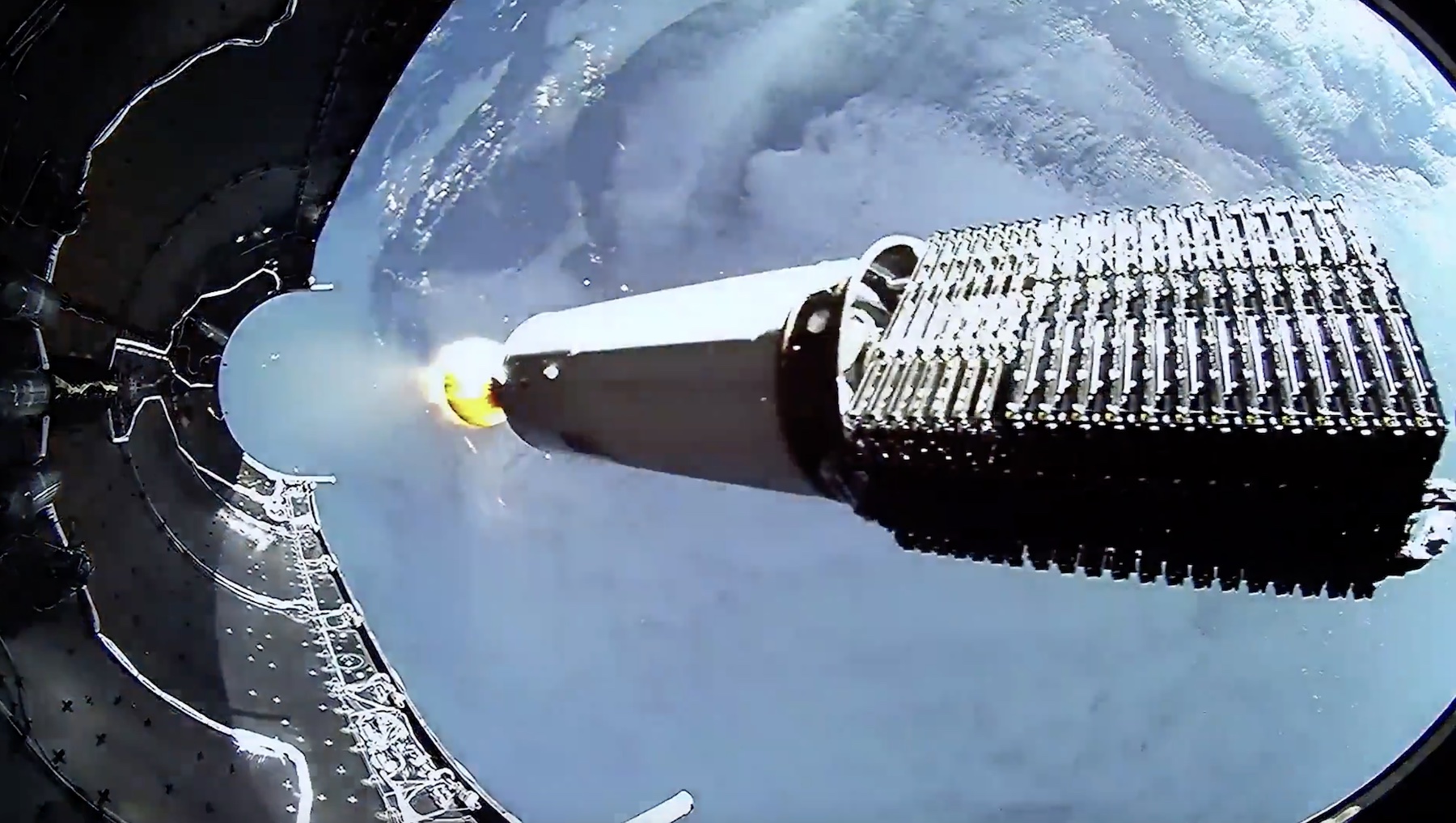

Falcon 9 rideshare boosts Vast ambitions. A pathfinder mission for Vast’s privately owned space station launched into orbit Sunday and promptly extended its solar panel, kicking off a shakedown cruise to prove the company’s designs can meet the demands of spaceflight, Ars reports. Vast’s Haven Demo mission lifted off just after midnight Sunday from Cape Canaveral Space Force Station, Florida, and rode a SpaceX Falcon 9 rocket into orbit. Haven Demo was one of 18 satellites sharing a ride on SpaceX’s Bandwagon 4 mission, launching alongside a South Korean spy satellite and a small testbed for Starcloud, a startup working with Nvidia to build an orbital data center.

Subscale testing … After release from the Falcon 9, the half-ton Haven Demo spacecraft stabilized itself and extended its power-generating solar array. The satellite captured 4K video of the solar array deployment, and Vast shared the beauty shot on social media. “Haven Demo’s mission success has turned us into a proven spacecraft company,” Vast’s CEO, Max Haot, posted on X. “The next step will be to become an actual commercial space station company next year. Something no one has achieved yet.” Vast plans to launch its first human-rated habitat, named Haven-1, into low-Earth orbit in 2026. Haven Demo lacks crew accommodations but carries several systems that are “architecturally similar” to Haven-1, according to Vast. For example, Haven-1 will have 12 solar arrays, each identical to the single array on Haven Demo. The pathfinder mission uses a subset of Haven-1’s propulsion system, but with identical thrusters, valves, and tanks.

Lights out at Vostochny. One of Russia’s most important projects over the last 15 years has been the construction of the Vostochny spaceport as the country seeks to fly its rockets from native soil and modernize its launch operations. Progress has been slow as corruption clouded Vostochny’s development. Now, the primary contractor building the spaceport, the Kazan Open Stock Company (PSO Kazan), has failed to pay its bills, Ars reports. The story, first reported by the Moscow Times, says that the energy company supplying Vostochny cut off electricity to areas of the spaceport still under construction after PSO Kazan racked up $627,000 in unpaid energy charges. The electricity company did so, it said, “to protect the interests of the region’s energy system.”

A dark reputation … Officials at the government-owned spaceport said PSO Kazan would repay its debt by the end of November, but the local energy company said it intends to file a lawsuit against KSO Kazan to declare the entity bankrupt. The two operational launch pads at Vostochny are apparently not affected by the power cuts. Vostochny has been a fiasco from the start. After construction began in 2011, the project was beset by hunger strikes, claims of unpaid workers, and the theft of $126 million. Additionally, a man driving a diamond-encrusted Mercedes was arrested after embezzling $75,000. Five years ago, there was another purge of top officials after another round of corruption.

Ariane 6 delivers for Europe again. European launch services provider Arianespace has successfully launched the Sentinel 1D Earth observation satellite aboard an Ariane 62 rocket for the European Commission, European Spaceflight reports. Launched in its two-booster configuration, the Ariane 6 rocket lifted off from the Guiana Space Center in South America on Tuesday. Approximately 34 minutes after liftoff, the satellite was deployed from the rocket’s upper stage into a Sun-synchronous orbit at an altitude of 693 kilometers (430 miles). Sentinel 1D is the newest spacecraft to join Europe’s Copernicus program, the world’s most expansive network of environmental monitoring satellites. The new satellite will extend Europe’s record of global around-the-clock radar imaging, revealing information about environmental disasters, polar ice cover, and the use of water resources.

Doubling cadence … This was the fourth flight of Europe’s new Ariane 6 rocket, and its third operational launch. Arianespace plans one more Ariane 62 launch to close out the year with a pair of Galileo navigation satellites. The company aims to double its Ariane 6 launch cadence in 2026, with between six and eight missions planned, according to David Cavaillès, Arianespace’s CEO. The European launch provider will open its 2026 manifest with the first flight of the more powerful four-booster variant of the rocket. If the company does manage eight Ariane 6 flights in 2026, it will already be close to reaching the stated maximum launch cadence of between nine and 10 flights per year.

India sets its own record for payload mass. The Indian Space Research Organization on Sunday successfully launched the Indian Navy’s advanced communication satellite GSAT-7R, or CMS-03, on an LVM3 rocket from the Satish Dhawan Space Center, The Hindu reports. The indigenously designed and developed satellite, weighing approximately 4.4 metric tons (9,700 pounds), is the heaviest satellite ever launched by an Indian rocket and marks a major milestone in strengthening the Navy’s space-based communications and maritime domain awareness.

Going heavy … The launch Sunday was India’s fourth of 2025, a decline from the country’s high-water mark of eight orbital launches in a year in 2023. The failure in May of India’s most-flown rocket, the PSLV, has contributed to this year’s slower launch cadence. India’s larger rockets, the GSLV and LVM3, have been more active while officials grounded the PSLV for an investigation into the launch failure. (submitted by EllPeaTea)

Blue Origin preps for second flight of New Glenn. The road to the second flight of Blue Origin’s heavy-lifting New Glenn rocket got a lot clearer this week. The company confirmed it is targeting Sunday, November 9, for the launch of New Glenn from Cape Canaveral Space Force Station, Florida. This follows a successful test-firing of the rocket’s seven BE-4 main engines last week, Ars reports. Blue Origin, the space company owned by billionaire Jeff Bezos, said the engines operated at full power for 22 seconds, generating nearly 3.9 million pounds of thrust on the launch pad.

Fully integrated … With the launch date approaching, engineers worked this week to attach the rocket’s payload shroud containing two NASA satellites set to embark on a journey to Mars. Now that the rocket is fully integrated, ground crews will roll it back to Blue Origin’s Launch Complex-36 (LC-36) for final countdown preps. The launch window on Sunday opens at 2: 45 pm EST (19: 45 UTC). Blue Origin is counting on recovering the New Glenn first stage on the next flight after missing the landing on the rocket’s inaugural mission in January. Officials plan to reuse this booster on the third New Glenn launch early next year, slated to propel Blue Origin’s first unpiloted Blue Moon lander toward the Moon.

Next three launches

Nov. 8: Falcon 9 | Starlink 10-51 | Kennedy Space Center, Florida | 08: 30 UTC

Nov. 8: Long March 11H| Unknown Payload | Haiyang Spaceport, China Coastal Waters | 21: 00 UTC

Nov. 9: New Glenn | ESCAPADE | Cape Canaveral Space Force Station, Florida | 19: 45 UTC

Rocket Report: Canada invests in sovereign launch; India flexes rocket muscles Read More »