Will space-based solar power ever make sense?

Is space-based solar power a costly, risky pipe dream? Or is it a viable way to combat climate change? Although beaming solar power from space to Earth could ultimately involve transmitting gigawatts, the process could be made surprisingly safe and cost-effective, according to experts from Space Solar, the European Space Agency, and the University of Glasgow.

But we’re going to need to move well beyond demonstration hardware and solve a number of engineering challenges if we want to develop that potential.

Designing space-based solar

Beaming solar energy from space is not new; telecommunications satellites have been sending microwave signals generated by solar power back to Earth since the 1960s. But sending useful amounts of power is a different matter entirely.

“The idea [has] been around for just over a century,” said Nicol Caplin, deep space exploration scientist at the ESA, on a Physics World podcast. “The original concepts were indeed sci-fi. It’s sort of rooted in science fiction, but then, since then, there’s been a trend of interest coming and going.”

Researchers are scoping out multiple designs for space-based solar power. Matteo Ceriotti, senior lecturer in space systems engineering at the University of Glasgow, wrote in The Conversation that many designs have been proposed.

The Solaris initiative is exploring two possible technologies, according to Sanjay Vijendran, lead for the Solaris initiative at the ESA: one that involves beaming microwaves from a station in geostationary orbit down to a receiver on Earth and another that involves using immense mirrors in a lower orbit to reflect sunlight down onto solar farms. He said he thinks that both of these solutions are potentially valuable. Microwave technology has drawn wider interest and was the main focus of these interviews. It has enormous potential, although high-frequency radio waves can also be used.

“You really have a source of 24/7 clean power from space,” Vijendran said. The power can be transmitted regardless of weather conditions because of the frequency of the microwaves.

“A 1-gigawatt power plant in space would be comparable to the top five solar farms on earth. A power plant with a capacity of 1 gigawatt could power around 875,000 households for one year,” said Andrew Glester, host of the Physics World podcast.

But we’re not ready to deploy anything like this. “It will be a big engineering challenge,” Caplin said. There are a number of physical hurdles involved in successfully building a solar power station in space.

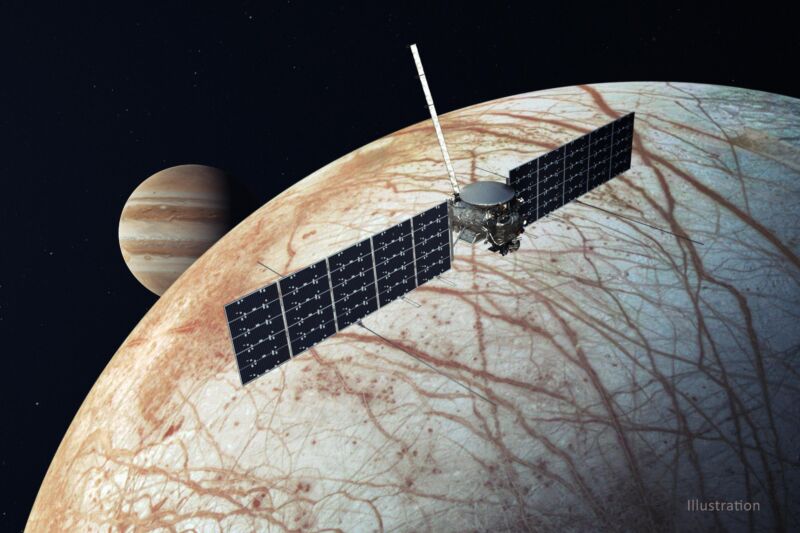

Using microwave technology, the solar array for an orbiting power station that generates a gigawatt of power would have to be over 1 square kilometer in size, according to a Nature article by senior reporter Elizabeth Gibney. “That’s more than 100 times the size of the International Space Station, which took a decade to build.” It would also need to be assembled robotically, since the orbiting facility would be uncrewed.

The solar cells would need to be resilient to space radiation and debris. They would also need to be efficient and lightweight, with a power-to-weight ratio 50 times more than the typical silicon solar cell, Gibney wrote. Keeping the cost of these cells down is another factor that engineers have to take into consideration. Reducing the losses during power transmission is another challenge, Gibney wrote. The energy conversion rate needs to be improved to 10–15 percent, according to the ESA. This would require technical advances.

Space Solar is working on a satellite design called CASSIOPeiA, which Physics World describes as looking “like a spiral staircase, with the photovoltaic panels being the ‘treads’ and the microwave transmitters—rod-shaped dipoles—being the ‘risers.’” It has a helical shape with no moving parts.

“Our system’s comprised of hundreds of thousands of the same dinner-plate-sized power modules. Each module has the PV which converts the sun’s energy into DC electricity,” said Sam Adlen, CEO of Space Solar.

“That DC power then drives electronics to transmit the power… down toward Earth from dipole antennas. That power up in space is converted to [microwaves] and beamed down in a coherent beam down to the Earth where it’s received by a rectifying antenna, reconverted into electricity, and input to the grid.”

Adlen said that robotics technologies for space applications, such as in-orbit assembly, are advancing rapidly.

Ceriotti wrote that SPS-ALPHA, another design, has a large solar-collector structure that includes many heliostats, which are modular small reflectors that can be moved individually. These concentrate sunlight onto separate power-generating modules, after which it’s transmitted back to Earth by yet another module.

Will space-based solar power ever make sense? Read More »