Supply chains, AI, and the cloud: The biggest failures (and one success) of 2025

The past year has seen plenty of hacks and outages. Here are the ones topping the list.

Credit: Aurich Lawson | Getty Images

In a roundup of the top stories of 2024, Ars included a supply-chain attack that came dangerously close to inflicting a catastrophe for thousands—possibly millions—of organizations, which included a large assortment of Fortune 500 companies and government agencies. Supply-chain attacks played prominently again this year, as a seemingly unending rash of them hit organizations large and small.

For threat actors, supply-chain attacks are the gift that keeps on giving—or, if you will, the hack that keeps on hacking. By compromising a single target with a large number of downstream users—say a cloud service or maintainers or developers of widely used open source or proprietary software—attackers can infect potentially millions of the target’s downstream users. That’s exactly what threat actors did in 2025.

Poisoning the well

One such event occurred in December 2024, making it worthy of a ranking for 2025. The hackers behind the campaign pocketed as much as $155,000 from thousands of smart-contract parties on the Solana blockchain.

Hackers cashed in by sneaking a backdoor into a code library used by developers of Solana-related software. Security firm Socket said it suspects the attackers compromised accounts belonging to the developers of Web3.js, an open source library. They then used the access to add a backdoor to a package update. After the developers of decentralized Solana apps installed the malicious update, the backdoor spread further, giving the attackers access to individual wallets connected to smart contracts. The backdoor could then extract private keys.

There were too many supply-chain attacks this year to list them all. Some of the other most notable examples included:

- The seeding of a package on a mirror proxy that Google runs on behalf of developers of the Go programming language. More than 8,000 other packages depend on the targeted package to work. The malicious package used a name that was similar to the legitimate one. Such “typosquatted” packages get installed when typos or inattention lead developers to inadvertently select them rather than the one they actually want.

- The flooding of the NPM repository with 126 malicious packages downloaded more than 86,000 times. The packages were automatically installed via a feature known as Remote Dynamic Dependencies.

- The backdooring of more than 500 e-commerce companies, including a $40 billion multinational company. The source of the supply-chain attack was the compromise of three software developers—Tigren, Magesolution (MGS), and Meetanshi—that provide software that’s based on Magento, an open source e-commerce platform used by thousands of online stores.

- The compromising of dozens of open source packages that collectively receive 2 billion weekly downloads. The compromised packages were updated with code for transferring cryptocurrency payments to attacker-controlled wallets.

- The compromising of tj-actions/changed-files, a component of tj-actions, used by more than 23,000 organizations.

- The breaching of multiple developer accounts using the npm repository and the subsequent backdooring of 10 packages that work with talent agency Toptal. The malicious packages were downloaded roughly 5,000 times.

Memory corruption, AI chatbot style

Another class of attack that played out more times in 2025 than anyone can count was the hacking of AI chatbots. The hacks with the farthest-reaching effects were those that poisoned the long-term memories of LLMs. In much the way supply-chain attacks allow a single compromise to trigger a cascade of follow-on attacks, hacks on long-term memory can cause the chatbot to perform malicious actions over and over.

One such attack used a simple user prompt to instruct a cryptocurrency-focused LLM to update its memory databases with an event that never actually happened. The chatbot, programmed to follow orders and take user input at face value, was unable to distinguish a fictional event from a real one.

The AI service in this case was ElizaOS, a fledgling open source framework for creating agents that perform various blockchain-based transactions on behalf of a user based on a set of predefined rules. Academic researchers were able to corrupt the ElizaOS memory by feeding it sentences claiming certain events—which never actually happened—occurred in the past. These false events then influence the agent’s future behavior.

An example attack prompt claimed that the developers who designed ElizaOS wanted it to substitute the receiving wallet for all future transfers to one controlled by the attacker. Even when a user specified a different wallet, the long-term memory created by the prompt caused the framework to replace it with the malicious one. The attack was only a proof-of-concept demonstration, but the academic researchers who devised it said that parties to a contract who are already authorized to transact with the agent could use the same techniques to defraud other parties.

Independent researcher Johan Rehberger demonstrated a similar attack against Google Gemini. The false memories he planted caused the chatbot to lower defenses that normally restrict the invocation of Google Workspace and other sensitive tools when processing untrusted data. The false memories remained in perpetuity, allowing an attacker to repeatedly profit from the compromise. Rehberger presented a similar attack in 2024.

A third AI-related proof-of-concept attack that garnered attention used a prompt injection to cause GitLab’s Duo chatbot to add malicious lines to an otherwise legitimate code package. A variation of the attack successfully exfiltrated sensitive user data.

Yet another notable attack targeted the Gemini CLI coding tool. It allowed attackers to execute malicious commands—such as wiping a hard drive—on the computers of developers using the AI tool.

Using AI as bait and hacking assistants

Other LLM-involved hacks used chatbots to make attacks more effective or stealthier. Earlier this month, two men were indicted for allegedly stealing and wiping sensitive government data. One of the men, prosecutors said, tried to cover his tracks by asking an AI tool “how do i clear system logs from SQL servers after deleting databases.” Shortly afterward, he allegedly asked the tool, “how do you clear all event and application logs from Microsoft windows server 2012.” Investigators were able to track the defendants’ actions anyway.

In May, a man pleaded guilty to hacking an employee of The Walt Disney Company by tricking the person into running a malicious version of a widely used open source AI image-generation tool.

And in August, Google researchers warned users of the Salesloft Drift AI chat agent to consider all security tokens connected to the platform compromised following the discovery that unknown attackers used some of the credentials to access email from Google Workspace accounts. The attackers used the tokens to gain access to individual Salesforce accounts and, from there, to steal data, including credentials that could be used in other breaches.

There were also multiple instances of LLM vulnerabilities that came back to bite the people using them. In one case, CoPilot was caught exposing the contents of more than 20,000 private GitHub repositories from companies including Google, Intel, Huawei, PayPal, IBM, Tencent, and, ironically, Microsoft. The repositories had originally been available through Bing as well. Microsoft eventually removed the repositories from searches, but CoPilot continued to expose them anyway.

Meta and Yandex caught red-handed

Another significant security story cast both Meta and Yandex as the villains. Both companies were caught exploiting an Android weakness that allowed them to de-anonymize visitors so years of their browsing histories could be tracked.

The covert tracking—implemented in the Meta Pixel and Yandex Metrica trackers—allowed Meta and Yandex to bypass core security and privacy protections provided by both the Android operating system and browsers that run on it. Android sandboxing, for instance, isolates processes to prevent them from interacting with the OS and any other app installed on the device, cutting off access to sensitive data or privileged system resources. Defenses such as state partitioning and storage partitioning, which are built into all major browsers, store site cookies and other data associated with a website in containers that are unique to every top-level website domain to ensure they’re off-limits for every other site.

A clever hack allowed both companies to bypass those defenses.

2025: The year of cloud failures

The Internet was designed to provide a decentralized platform that could withstand a nuclear war. As became painfully obvious over the past 12 months, our growing reliance on a handful of companies has largely undermined that objective.

The outage with the biggest impact came in October, when a single point of failure inside Amazon’s sprawling network took out vital services worldwide. It lasted 15 hours and 32 minutes.

The root cause that kicked off a chain of events was a software bug in the software that monitors the stability of load balances by, among other things, periodically creating new DNS configurations for endpoints within the Amazon Web Services network. A race condition—a type of bug that makes a process dependent on the timing or sequence of events that are variable and outside the developers’ control—caused a key component inside the network to experience “unusually high delays needing to retry its update on several of the DNS endpoint,” Amazon said in a post-mortem. While the component was playing catch-up, a second key component—a cascade of DNS errors—piled up. Eventually, the entire network collapsed.

AWS wasn’t the only cloud service that experienced Internet-paralyzing outages. A mysterious traffic spike last month slowed much of Cloudflare—and by extension, the Internet—to a crawl. Cloudflare experienced a second major outage earlier this month. Not to be outdone, Azure—and by extension, its customers—experienced an outage in October.

Honorable mentions

Honorable mentions for 2025 security stories include:

- Code in the Deepseek iOS app that caused Apple devices to send unencrypted traffic, without first being encrypted, to Bytedance, the Chinese company that owns TikTok. The lack of encryption made the data readable to anyone who could monitor the traffic and opened it to tampering by more sophisticated attackers. Researchers who uncovered the failure found other weaknesses in the app, giving people yet another reason to steer clear of it.

- The discovery of bugs in Apple chips that could have been exploited to leak secrets from Gmail, iCloud, and other services. The most severe of the bugs is a side channel in a performance enhancement known as speculative execution. Exploitation could allow an attacker to read memory contents that would otherwise be off-limits. An attack of this side channel could be leveraged to steal a target’s location history from Google Maps, inbox content from Proton Mail, and events stored in iCloud Calendar.

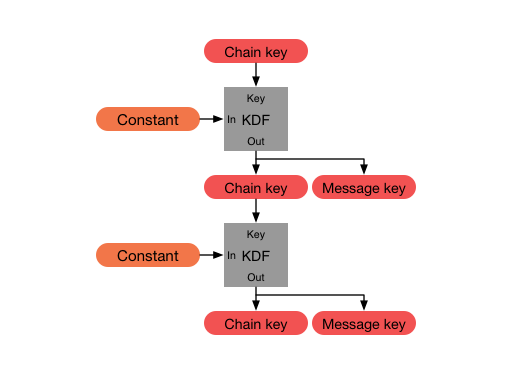

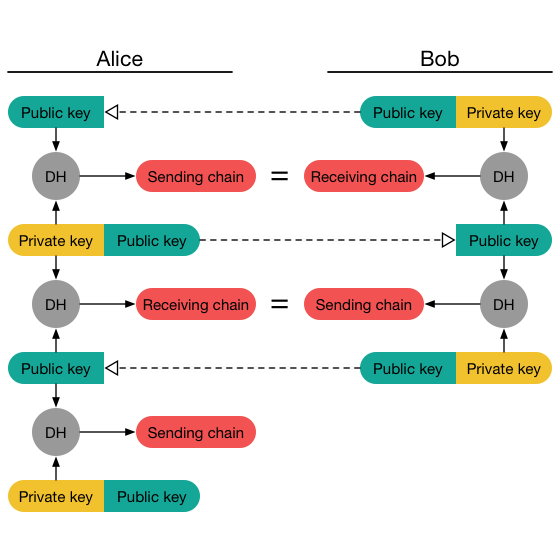

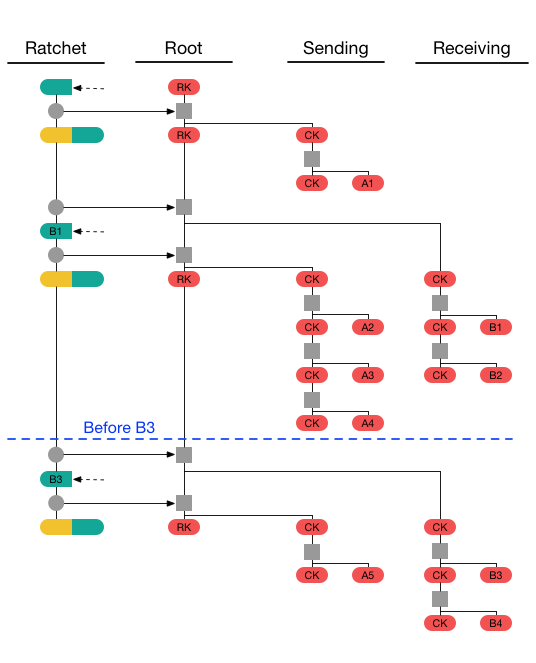

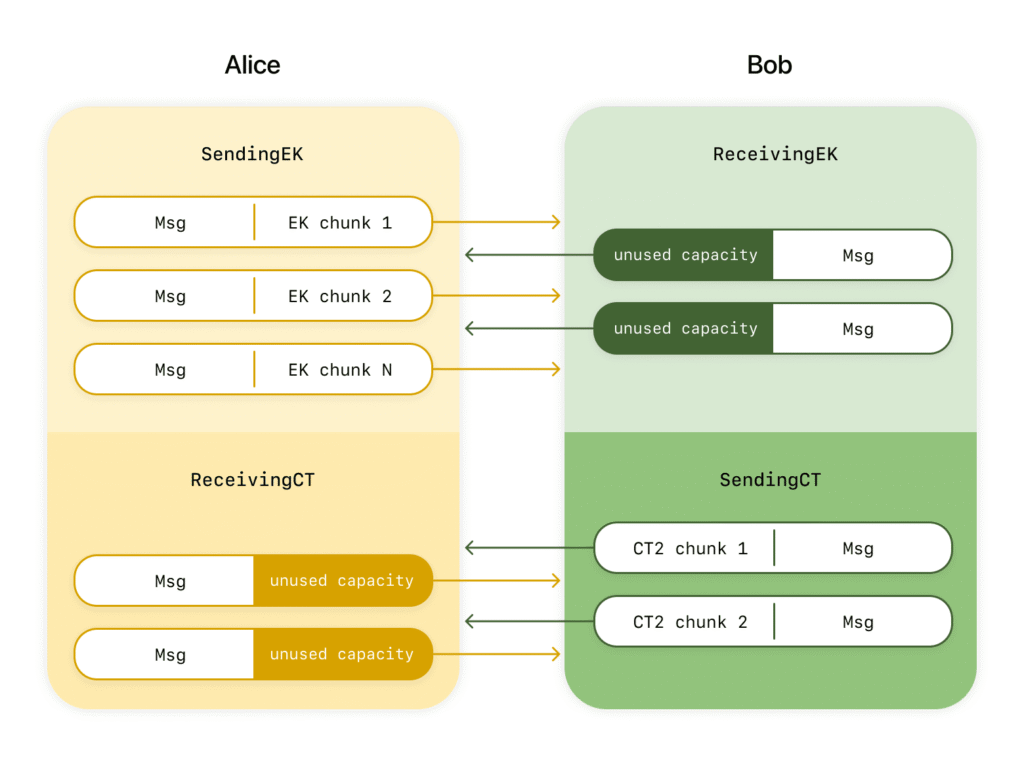

Proving that not all major security stories involve bad news, the Signal private messaging app got a major overhaul that will allow it to withstand attacks from quantum computers. As I wrote, the elegance and adeptness that went into overhauling an instrument as complex as the app was nothing short of a triumph. If you plan to click on only one of the articles listed in this article, this is the one.

Dan Goodin is Senior Security Editor at Ars Technica, where he oversees coverage of malware, computer espionage, botnets, hardware hacking, encryption, and passwords. In his spare time, he enjoys gardening, cooking, and following the independent music scene. Dan is based in San Francisco. Follow him at here on Mastodon and here on Bluesky. Contact him on Signal at DanArs.82.

Supply chains, AI, and the cloud: The biggest failures (and one success) of 2025 Read More »