Study: Social media probably can’t be fixed

It’s no secret that much of social media has become profoundly dysfunctional. Rather than bringing us together into one utopian public square and fostering a healthy exchange of ideas, these platforms too often create filter bubbles or echo chambers. A small number of high-profile users garner the lion’s share of attention and influence, and the algorithms designed to maximize engagement end up merely amplifying outrage and conflict, ensuring the dominance of the loudest and most extreme users—thereby increasing polarization even more.

Numerous platform-level intervention strategies have been proposed to combat these issues, but according to a preprint posted to the physics arXiv, none of them are likely to be effective. And it’s not the fault of much-hated algorithms, non-chronological feeds, or our human proclivity for seeking out negativity. Rather, the dynamics that give rise to all those negative outcomes are structurally embedded in the very architecture of social media. So we’re probably doomed to endless toxic feedback loops unless someone hits upon a brilliant fundamental redesign that manages to change those dynamics.

Co-authors Petter Törnberg and Maik Larooij of the University of Amsterdam wanted to learn more about the mechanisms that give rise to the worst aspects of social media: the partisan echo chambers, the concentration of influence among a small group of elite users (attention inequality), and the amplification of the most extreme divisive voices. So they combined standard agent-based modeling with large language models (LLMs), essentially creating little AI personas to simulate online social media behavior. “What we found is that we didn’t need to put any algorithms in, we didn’t need to massage the model,” Törnberg told Ars. “It just came out of the baseline model, all of these dynamics.”

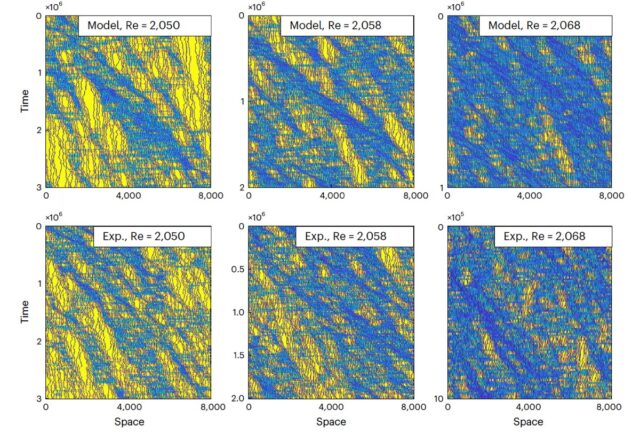

They then tested six different intervention strategies social scientists have been proposed to counter those effects: switching to chronological or randomized feeds; inverting engagement-optimization algorithms to reduce the visibility of highly reposted sensational content; boosting the diversity of viewpoints to broaden users’ exposure to opposing political views; using “bridging algorithms” to elevate content that fosters mutual understanding rather than emotional provocation; hiding social statistics like reposts and follower accounts to reduce social influence cues; and removing biographies to limit exposure to identity-based signals.

The results were far from encouraging. Only some interventions showed modest improvements. None were able to fully disrupt the fundamental mechanisms producing the dysfunctional effects. In fact, some interventions actually made the problems worse. For example, chronological ordering had the strongest effect on reducing attention inequality, but there was a tradeoff: It also intensified the amplification of extreme content. Bridging algorithms significantly weakened the link between partisanship and engagement and modestly improved viewpoint diversity, but it also increased attention inequality. Boosting viewpoint diversity had no significant impact at all.

So is there any hope of finding effective intervention strategies to combat these problematic aspects of social media? Or should we nuke our social media accounts altogether and go live in caves? Ars caught up with Törnberg for an extended conversation to learn more about these troubling findings.

Ars Technica: What drove you to conduct this study?

Petter Törnberg: For the last 20 years or so, there has been a ton of research on how social media is reshaping politics in different ways, almost always using observational data. But in the last few years, there’s been a growing appetite for moving beyond just complaining about these things and trying to see how we can be a bit more constructive. Can we identify how to improve social media and create online spaces that are actually living up to those early promises of providing a public sphere where we can deliberate and debate politics in a constructive way?

The problem with using observational data is that it’s very hard to test counterfactuals to implement alternative solutions. So one kind of method that has existed in the field is agent-based simulations and social simulations: create a computer model of the system and then run experiments on that and test counterfactuals. It is useful for looking at the structure and emergence of network dynamics.

But at the same time, those models represent agents as simple rule followers or optimizers, and that doesn’t capture anything of the cultural world or politics or human behavior. I’ve always been of the controversial opinion that those things actually matter, especially for online politics. We need to study both the structural dynamics of network formations and the patterns of cultural interaction.

Ars Technica: So you developed this hybrid model that combines LLMs with agent-based modeling.

Petter Törnberg: That’s the solution that we find to move beyond the problems of conventional agent-based modeling. Instead of having this simple rule of followers or optimizers, we use AI or LLMs. It’s not a perfect solution—there’s all kind of biases and limitations—but it does represent a step forward compared to a list of if/then rules. It does have something more of capturing human behavior in a more plausible way. We give them personas that we get from the American National Election Survey, which has very detailed questions about US voters and their hobbies and preferences. And then we turn that into a textual persona—your name is Bob, you’re from Massachusetts, and you like fishing—just to give them something to talk about and a little bit richer representation.

And then they see the random news of the day, and they can choose to post the news, read posts from other users, repost them, or they can choose to follow users. If they choose to follow users, they look at their previous messages, look at their user profile.

Our idea was to start with the minimal bare-bones model and then add things to try to see if we could reproduce these problematic consequences. But to our surprise, we actually didn’t have to add anything because these problematic consequences just came out of the bare bones model. This went against our expectations and also what I think the literature would say.

Ars Technica: I’m skeptical of AI in general, particularly in a research context, but there are very specific instances where it can be extremely useful. This strikes me as one of them, largely because your basic model proved to be so robust. You got the same dynamics without introducing anything extra.

Petter Törnberg: Yes. It’s been a big conversation in social science over the last two years or so. There’s a ton of interest in using LLMs for social simulation, but no one has really figured out for what or how it’s going to be helpful, or how we’re going to get past these problems of validity and so on. The kind of approach that we take in this paper is building on a tradition of complex systems thinking. We imagine very simple models of the human world and try to capture very fundamental mechanisms. It’s not really aiming to be realistic or a precise, complete model of human behavior.

I’ve been one of the more critical people of this method, to be honest. At the same time, it’s hard to imagine any other way of studying these kinds of dynamics where we have cultural and structural aspects feeding back into each other. But I still have to take the findings with a grain of salt and realize that these are models, and they’re capturing a kind of hypothetical world—a spherical cow in a vacuum. We can’t predict what someone is going to have for lunch on Tuesday, but we can capture broader mechanisms, and we can see how robust those mechanisms are. We can see whether they’re stable, unstable, which conditions they emerge in, and the general boundaries. And in this case, we found a mechanism that seems to be very robust, unfortunately.

Ars Technica: The dream was that social media would help revitalize the public sphere and support the kind of constructive political dialogue that your paper deems “vital to democratic life.” That largely hasn’t happened. What are the primary negative unexpected consequences that have emerged from social media platforms?

Petter Törnberg: First, you have echo chambers or filter bubbles. The risk of broad agreement is that if you want to have a functioning political conversation, functioning deliberation, you do need to do that across the partisan divide. If you’re only having a conversation with people who already agree with each other, that’s not enough. There’s debate on how widespread echo chambers are online, but it is quite established that there are a lot of spaces online that aren’t very constructive because there’s only people from one political side. So that’s one ingredient that you need. You need to have a diversity of opinion, a diversity of perspective.

The second one is that the deliberation needs to be among equals; people need to have more or less the same influence in the conversation. It can’t be completely controlled by a small, elite group of users. This is also something that people have pointed to on social media: It has a tendency of creating these influencers because attention attracts attention. And then you have a breakdown of conversation among equals.

The final one is what I call (based on Chris Bail’s book) the social media prism. The more extreme users tend to get more attention online. This is often discussed in relation to engagement algorithms, which tend to identify the type of content that most upsets us and then boost that content. I refer to it as a “trigger bubble” instead of the filter bubble. They’re trying to trigger us as a way of making us engage more so they can extract our data and keep our attention.

Ars Technica: Your conclusion is that there’s something within the structural dynamics of the network itself that’s to blame—something fundamental to the construction of social networks that makes these extremely difficult problems to solve.

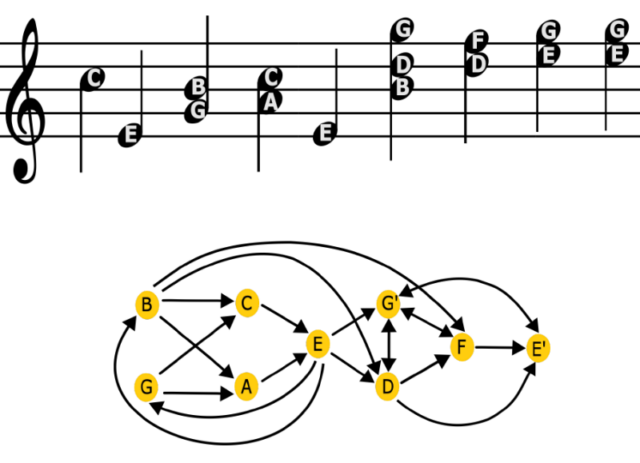

Petter Törnberg: Exactly. It comes from the fact that we’re using these AI models to capture a richer representation of human behavior, which allows us to see something that wouldn’t really be possible using conventional agent-based modeling. There have been previous models looking at the growth of social networks on social media. People choose to retweet or not, and we know that action tends to be very reactive. We tend to be very emotional in that choice. And it tends to be a highly partisan and polarized type of action. You hit retweet when you see someone being angry about something, or doing something horrific, and then you share that. It’s well-known that this leads to toxic, more polarized content spreading more.

But what we find is that it’s not just that this content spreads; it also shapes the network structures that are formed. So there’s feedback between the effective emotional action of choosing to retweet something and the network structure that emerges. And then in turn, you have a network structure that feeds back what content you see, resulting in a toxic network. The definition of an online social network is that you have this kind of posting, reposting, and following dynamics. It’s quite fundamental to it. That alone seems to be enough to drive these negative outcomes.

Ars Technica: I was frankly surprised at the ineffectiveness of the various intervention strategies you tested. But it does seem to explain the Bluesky conundrum. Bluesky has no algorithm, for example, yet the same dynamics still seem to emerge. I think Bluesky’s founders genuinely want to avoid those dysfunctional issues, but they might not succeed, based on this paper. Why are such interventions so ineffective?

Petter Törnberg: We’ve been discussing whether these things are due to the platforms doing evil things with algorithms or whether we as users are choosing that we want a bad environment. What we’re saying is that it doesn’t have to be either of those. This is often the unintended outcomes from interactions based on underlying rules. It’s not necessarily because the platforms are evil; it’s not necessarily because people want to be in toxic, horrible environments. It just follows from the structure that we’re providing.

We tested six different interventions. Google has been trying to make social media less toxic and recently released a newsfeed algorithm based on the content of the text. So that’s one example. We’re also trying to do more subtle interventions because often you can find a certain way of nudging the system so it switches over to healthier dynamics. Some of them have moderate or slightly positive effects on one of the attributes, but then they often have negative effects on another attribute, or they have no impact whatsoever.

I should say also that these are very extreme interventions in the sense that, if you depended on making money on your platform, you probably don’t want to implement them because it probably makes it really boring to use. It’s like showing the least influential users, the least retweeted messages on the platform. Even so, it doesn’t really make a difference in changing the basic outcomes. What we take from that is that the mechanism producing these problematic outcomes is really robust and hard to resolve given the basic structure of these platforms.

Ars Technica: So how might one go about building a successful social network that doesn’t have these problems?

Petter Törnberg: There are several directions where you could imagine going, but there’s also the constraint of what is popular use. Think back to the early Internet, like ICQ. ICQ had this feature where you could just connect to a random person. I loved it when I was a kid. I would talk to random people all over the world. I was 12 in the countryside on a small island in Sweden, and I was talking to someone from Arizona, living a different life. I don’t know how successful that would be these days, the Internet having become a lot less innocent than it was.

For instance, we can focus on the question of inequality of attention, a very well-studied and robust feature of these networks. I personally thought we would be able to address it with our interventions, but attention draws attention, and this leads to a power law distribution, where 1 percent [of users] dominates the entire conversation. We know the conditions under which those power laws emerge. This is one of the main outcomes of social network dynamics: extreme inequality of attention.

But in social science, we always teach that everything is a normal distribution. The move from studying the conventional social world to studying the online social world means that you’re moving from these nice normal distributions to these horrible power law distributions. Those are the outcomes of having social networks where the probability of connecting to someone depends on how many previous connections they have. If we want to get rid of that, we probably have to move away from the social network model and have some kind of spatial model or group-based model that makes things a little bit more local, a little bit less globally interconnected.

Ars Technica: It sounds like you’d want to avoid those big influential nodes that play such a central role in a large, complex global network.

Petter Törnberg: Exactly. I think that having those global networks and structures fundamentally undermines the possibility of the kind of conversations that political scientists and political theorists traditionally talked about when they were discussing in the public square. They were talking about social interaction in a coffee house or a tea house, or reading groups and so on. People thought the Internet was going to be precisely that. It’s very much not that. The dynamics are fundamentally different because of those structural differences. We shouldn’t expect to be able to get a coffee house deliberation structure when we have a global social network where everyone is connected to everyone. It is difficult to imagine a functional politics building on that.

Ars Technica: I want to come back to your comment on the power law distribution, how 1 percent of people dominate the conversation, because I think that is something that most users routinely forget. The horrible things we see people say on the Internet are not necessarily indicative of the vast majority of people in the world.

Petter Törnberg: For sure. That is capturing two aspects. The first is the social media prism, where the perspective we get of politics when we see it through the lens of social media is fundamentally different from what politics actually is. It seems much more toxic, much more polarized. People seem a little bit crazier than they really are. It’s a very well-documented aspect of the rise of polarization: People have a false perception of the other side. Most people have fairly reasonable and fairly similar opinions. The actual polarization is lower than the perceived polarization. And that arguably is a result of social media, how it misrepresents politics.

And then we see this very small group of users that become very influential who often become highly visible as a result of being a little bit crazy and outrageous. Social media creates an incentive structure that is really central to reshaping not just how we see politics but also what politics is, which politicians become powerful and influential, because it is controlling the distribution of what is arguably the most valuable form of capital of our era: attention. Especially for politicians, being able to control attention is the most important thing. And since social media creates the conditions of who gets attention or not, it creates an incentive structure where certain personalities work better in a way that’s just fundamentally different from how it was in previous eras.

Ars Technica: There are those who have sworn off social media, but it seems like simply not participating isn’t really a solution, either.

Petter Törnberg: No. First, even if you only read, say, The New York Times, that newspaper is still reshaped by what works on social media, the social media logic. I had a student who did a little project this last year showing that as social media became more influential, the headlines of The New York Times became more clickbaity and adapted to the style of what worked on social media. So conventional media and our very culture is being transformed.

But more than that, as I was just saying, it’s the type of politicians, it’s the type of people who are empowered—it’s the entire culture. Those are the things that are being transformed by the power of the incentive structures of social media. It’s not like, “This is things that are happening in social media and this is the rest of the world.” It’s all entangled, and somehow social media has become the cultural engine that is shaping our politics and society in very fundamental ways. Unfortunately.

Ars Technica: I usually like to say that technological tools are fundamentally neutral and can be used for good or ill, but this time I’m not so sure. Is there any hope of finding a way to take the toxic and turn it into a net positive?

Petter Törnberg: What I would say to that is that we are at a crisis point with the rise of LLMs and AI. I have a hard time seeing the contemporary model of social media continuing to exist under the weight of LLMs and their capacity to mass-produce false information or information that optimizes these social network dynamics. We already see a lot of actors—based on this monetization of platforms like X—that are using AI to produce content that just seeks to maximize attention. So misinformation, often highly polarized information as AI models become more powerful, that content is going to take over. I have a hard time seeing the conventional social media models surviving that.

We’ve already seen the process of people retreating in part to credible brands and seeking to have gatekeepers. Young people, especially, are going into WhatsApp groups and other closed communities. Of course, there’s misinformation from social media leaking into those chats also. But these kinds of crisis points at least have the hope that we’ll see a changing situation. I wouldn’t bet that it’s a situation for the better. You wanted me to sound positive, so I tried my best. Maybe it’s actually “good riddance.”

Ars Technica: So let’s just blow up all the social media networks. It still won’t be better, but at least we’ll have different problems.

Petter Törnberg: Exactly. We’ll find a new ditch.

DOI: arXiv, 2025. 10.48550/arXiv.2508.03385 (About DOIs).

Jennifer is a senior writer at Ars Technica with a particular focus on where science meets culture, covering everything from physics and related interdisciplinary topics to her favorite films and TV series. Jennifer lives in Baltimore with her spouse, physicist Sean M. Carroll, and their two cats, Ariel and Caliban.

Study: Social media probably can’t be fixed Read More »