Actually, we are going to tell you the odds of recovering New Glenn’s second launch

The only comparison available is SpaceX, with its Falcon 9 rocket. The company made its first attempt at a powered descent of the Falcon 9 into the ocean during its sixth launch in September 2013. On the vehicle’s ninth flight, it successfully made a controlled ocean landing. SpaceX made its first drone ship landing attempt in January 2015, a failure. Finally, on the vehicle’s 20th launch, SpaceX successfully put the Falcon 9 down on land, with the first successful drone ship landing following on the 23rd flight in April 2016.

SpaceX did not attempt to land every one of these 23 flights, but the company certainly experienced a number of failures as it worked to safely bring back an orbital rocket onto a small platform out at sea. Blue Origin’s engineers, some of whom worked at SpaceX at the time, have the benefit of those learnings. But it is still a very, very difficult thing to do on the second flight of a new rocket. The odds aren’t 3,720-to-1, but they’re probably not 75 percent, either.

Reuse a must for the bottom line

Nevertheless, for the New Glenn program to break even financially and eventually turn a profit, it must demonstrate reuse fairly quickly. According to multiple sources, the New Glenn first stage costs in excess of $100 million to manufacture. It is a rather exquisite piece of hardware, with many costs baked into the vehicle to make it rapidly reusable. But those benefits only come after a rocket is landed in good condition.

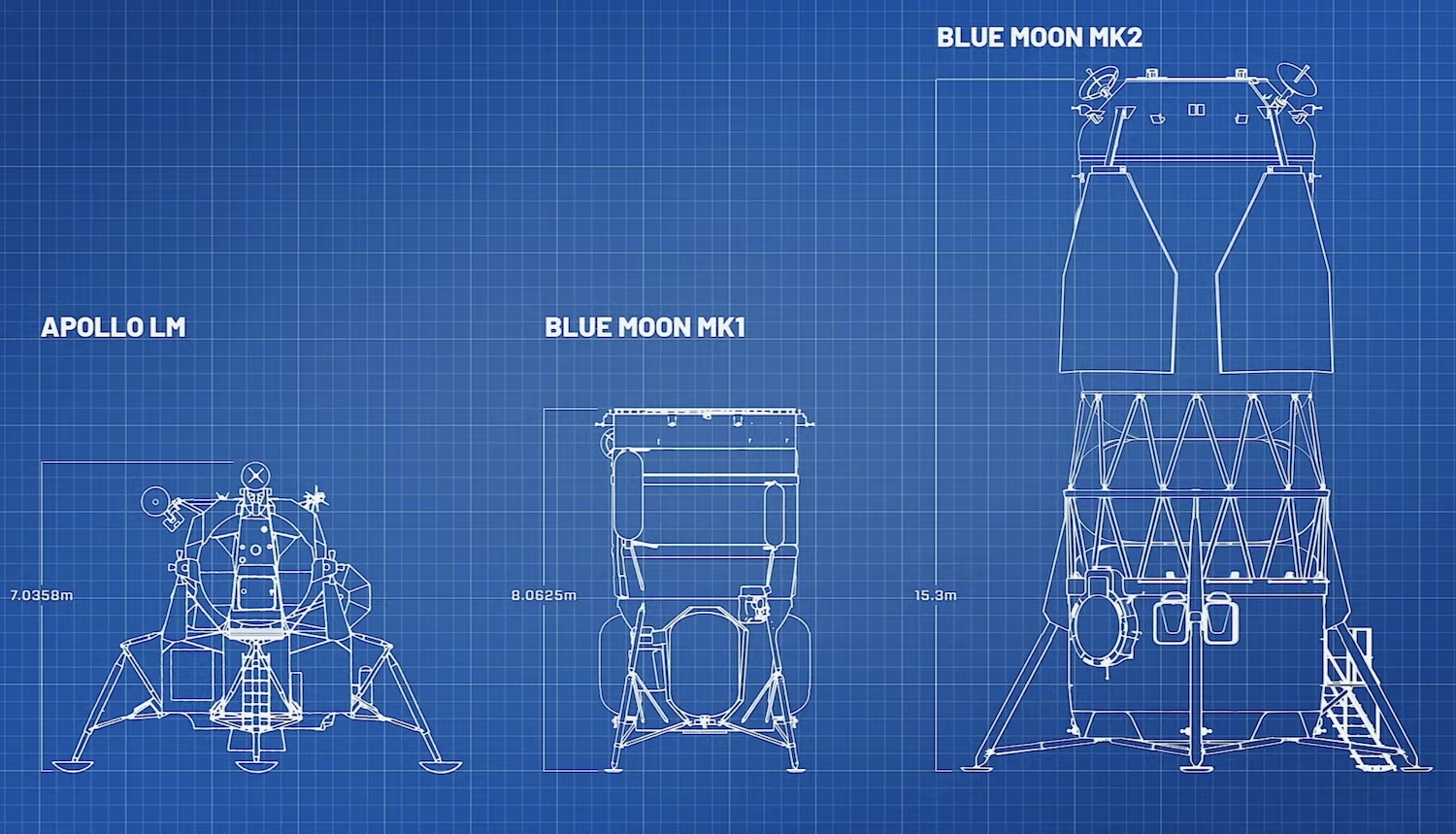

On its nominal plan, Blue Origin plans to refurbish the “Never Tell Me The Odds” booster for the New Glenn program’s third flight, a highly anticipated launch of the Mark 1 lunar lander. Such a refurbishment—again, on a nominal timeline—could be accomplished within 90 days. That seems unlikely, though. SpaceX did not reuse the first Falcon 9 booster it landed, and the first booster to re-fly required 356 days of analysis and refurbishment.

Nevertheless, we’re not supposed to talk about the odds with this mission. So instead, we’ll just note that the hustle and ambition from Blue Origin is a welcome addition to the space industry, which benefits from both.

Actually, we are going to tell you the odds of recovering New Glenn’s second launch Read More »