ULA aimed to launch up to 10 Vulcan rockets this year—it will fly just once

Engineers traced the problem to a manufacturing defect in an insulator on the solid rocket motor, and telemetry data from all four boosters on the following flight in August exhibited “spot-on” performance, according to Bruno. But officials decided to recover the spent expendable motor casings from the Atlantic Ocean for inspections to confirm there were no other surprises or close calls.

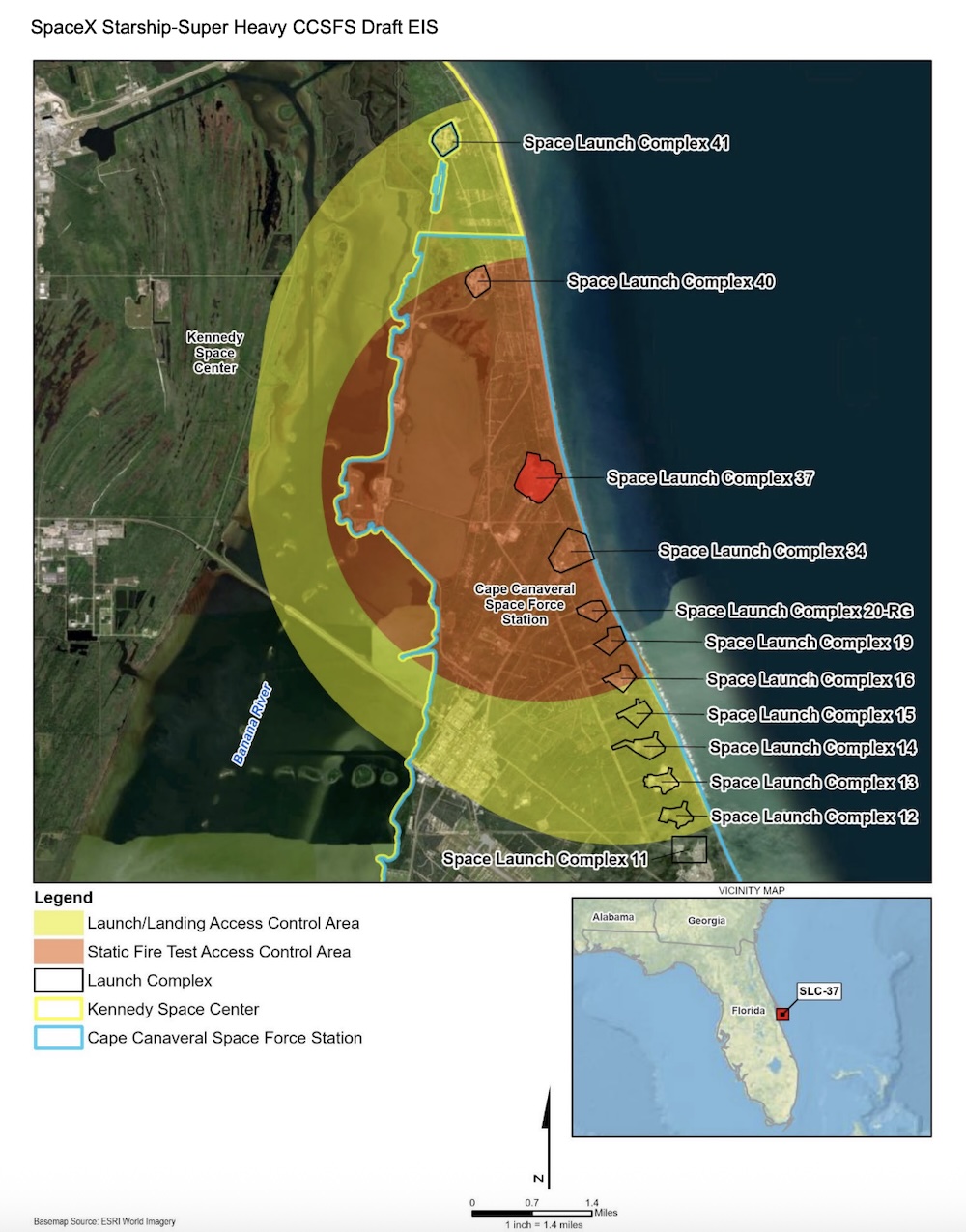

The hangup delaying the next Vulcan launches isn’t in rocket production. ULA has hardware for multiple Vulcan rockets in storage at Cape Canaveral Space Force Station, Florida.

Instead, one key reason for Vulcan’s past delays has been the rocket’s performance, particularly its solid rocket boosters. It isn’t clear whether the latest delays are related to the readiness of the Space Force’s GSSAP satellites (the next GPS satellite to fly on Vulcan has been available for launch since 2022), the inspections of Vulcan’s solid rocket motors, or something else.

Vulcan booster cores in storage at Cape Canaveral Space Force Station, Florida. Credit: United Launch Alliance

A Space Systems Command spokesperson told Ars that “appropriate actions are being executed to ensure a successful USSF-87 mission … The teams analyze all hardware as well as available data from previous missions to evaluate space flight worthiness of future missions.”

The spokesperson did not provide a specific answer to a question from Ars about inspections on the solid rocket motors from the most recent Vulcan flight.

ULA’s outfitting of a new rocket assembly hangar and a second mobile launch platform for the Vulcan rocket at Cape Canaveral has also seen delays. With so many launches in its backlog, ULA needs capacity to stack and prepare at least two rockets in different buildings at the same time. Eventually, the company’s goal is to launch at an average clip of twice per month.

On Monday, ground crews at Cape Canaveral moved the second Vulcan launch platform to the company’s launch pad for fit checks and “initial technical testing.” This is a good sign that the company is moving closer to ramping up the Vulcan launch cadence, but it’s now clear it won’t happen this year.

Vulcan’s slow launch rate since its first flight in January 2024 is not unusual for new rockets. It took 28 months for SpaceX’s Falcon 9 and ULA’s Atlas V to reach their fourth flight, a timeline that the Vulcan vehicle will reach in May 2026.

The Delta IV rocket from ULA flew its fourth mission 25 months after debuting in 2002. Europe’s Ariane 6 rocket reached its fourth flight in 16 months, but it shares more in common with its predecessor than the others. SpaceX’s Starship also had a faster ramp-up, with its fourth test flight coming less than 14 months after the first.

ULA aimed to launch up to 10 Vulcan rockets this year—it will fly just once Read More »