Why is Bezos trolling Musk on X with turtle pics? Because he has a new Moon plan.

“It’s time to go back to the Moon—this time to stay.”

Step by step, ferociously? Credit: Jeff Bezos/X

The founder of Amazon, Jeff Bezos, does not often post on the social media site owned by his rival Elon Musk. But on Monday, Bezos did, sharing a black-and-white image of a turtle emerging from the shadows on X.

The photo, which included no text, may have stumped some observers. Yet for anyone familiar with Bezos’ privately owned space company, Blue Origin, the message was clear. The company’s coat of arms prominently features two turtles, a reference to one of Aesop’s Fables, “The Tortoise and the Hare,” in which the slow and steady tortoise wins the race over a quicker but overconfident hare.

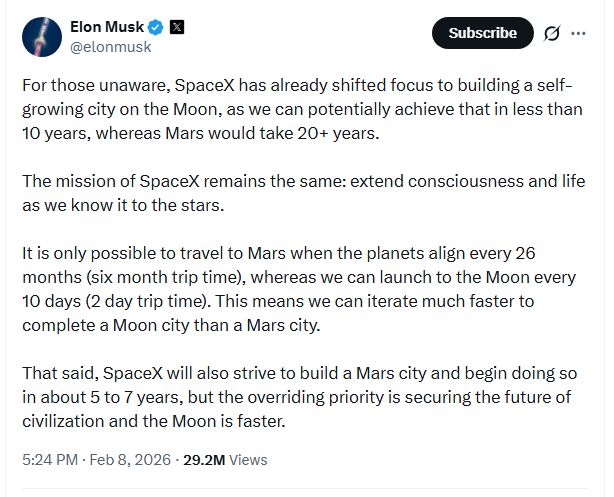

Bezos’ foray into social media turtle trolling came about 12 hours after Musk made major waves in the space community by announcing that SpaceX was pivoting toward the Moon, rather than Mars, as a near-term destination. It represented a huge shift in Musk’s thinking, as the SpaceX founder has long spoken of building a multi-planetary civilization on Mars.

Welcome to the Club

It must have provided Bezos with some self-satisfaction. He is also a believer in human settlement of space, but he has espoused the view that our spacefaring species should begin on the Moon and then build orbital space habitats. Back in 2019, when unveiling his vision, Bezos spoke about NASA’s goal of returning humans to the Moon through the Artemis Program. “I love this,” Bezos said. “It’s the right thing to do. We can help meet that timeline but only because we started three years ago. It’s time to go back to the Moon—this time to stay.”

So in posting an image of a turtle, Bezos was sending a couple of messages to Musk. First, it was something of a sequel to Bezos’ infamous “Welcome to the Club” tweet more than a decade ago. And secondly, Bezos was telling Musk that slow and steady wins the race. In other words, Bezos believes Blue Origin will beat SpaceX back to the Moon.

Why would Bezos, whose company has launched to orbit all of two times, think Blue Origin has a chance to compete with SpaceX (which has more than 600 orbital launches) to land humans on the Moon?

The answer can be found in a pair of documents obtained by Ars that outline an accelerated Artemis architecture that Blue Origin is now developing.

Some background on the Human Landing System

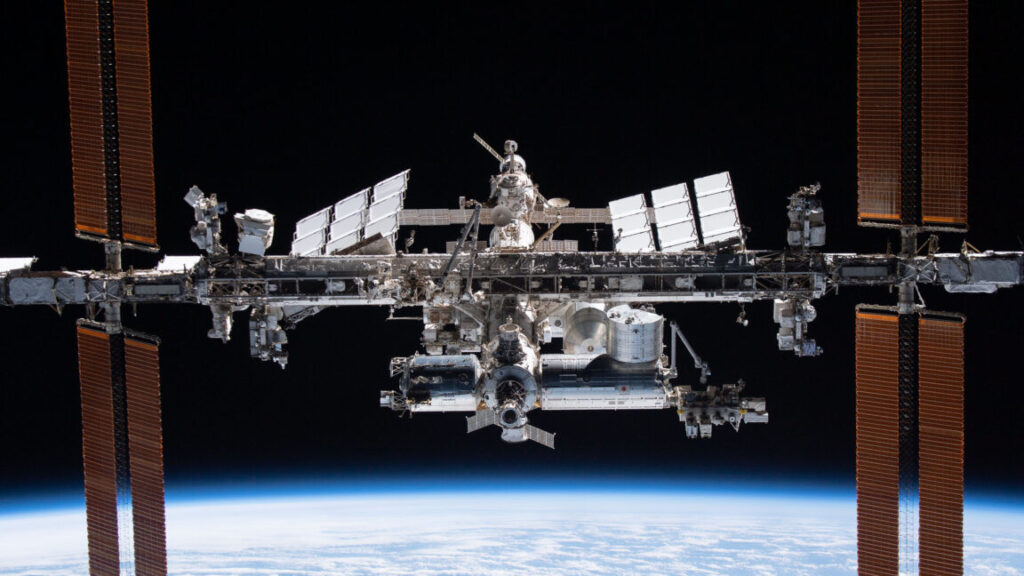

A little more than five years ago, NASA reached out to the US commercial space industry for help in building a lunar lander. This lander would dock with NASA’s Orion spacecraft to carry humans from an elliptical orbit around the Moon, known as a near-rectilinear halo orbit, down to the lunar surface and back up to Orion.

The story of what happened as part of this bidding process is long and convoluted (including lawsuits and remarkable graphics like this one from Blue Origin). However, what really matters is that, by 2023, both SpaceX and Blue Origin had contracts from NASA to develop lunar landers—SpaceX with Starship and Blue Origin with Blue Moon MK2—for crewed missions as part of the Artemis Program. Both mission architectures required propellant refueling, essentially the launch of “tankers” from Earth to transfer large amounts of fuel and oxidizer into low-Earth orbit to complete a lunar landing. SpaceX was considered to have a considerable lead on Blue Origin.

In 2025, again for complex reasons, it became clear that while these reusable landers were fantastic for a long-term lunar program, there were two problems. The first was that SpaceX blew up three Starships during testing last year, raising serious questions about whether the company would be ready to complete a lunar landing before 2030. And second, it was becoming clear that China may well have a simpler lander that could put taikonauts on the Moon before 2030.

Blue’s new plan

Last October, Ars revealed that Blue Origin was beginning to work on an “accelerated” architecture that could potentially land humans on the Moon before 2030 without requiring orbital refueling. Now, thanks to some new documents, we know what those landings could look like. The screenshots shared with Ars show two different missions, an uncrewed “demo” flight and a crewed Moon landing. Here’s what they entail:

Uncrewed demo mission: This requires three launches of the New Glenn rocket. The first two launches each put a “Transfer stage” into low-Earth orbit. The third launch puts a “Blue Moon MK2-IL” into orbit. (The “IL” stands for Initial Lander, and it appears to be a smaller version of the Blue Moon MK2 lander.) All three vehicles dock, and the first transfer stage boosts the stack to an elliptical orbit around Earth (after this, the stage burns up in Earth’s atmosphere). The second transfer stage then boosts the MK-2 lander from Earth orbit into a 15×100 km orbit above the Moon. From here, the MK-2 lander separates and goes down to the Moon, later ascending back to low-lunar orbit.

Crewed demo mission: This requires four launches of the New Glenn rocket. The first three launches each put a “Transfer stage” into low-Earth orbit. A fourth launch puts the MK2-IL lander into orbit and the vehicles dock. The first transfer stage pushes the stack into an elliptical Earth orbit. The second transfer stage pushes the stack to rendezvous with Orion in a near-rectilinear halo orbit. After the crew boards, the third and final transfer stage pushes the MK-2 lander into a low-lunar orbit before separating. The lander goes down to the Moon and then ascends to re-rendezvous with Orion.

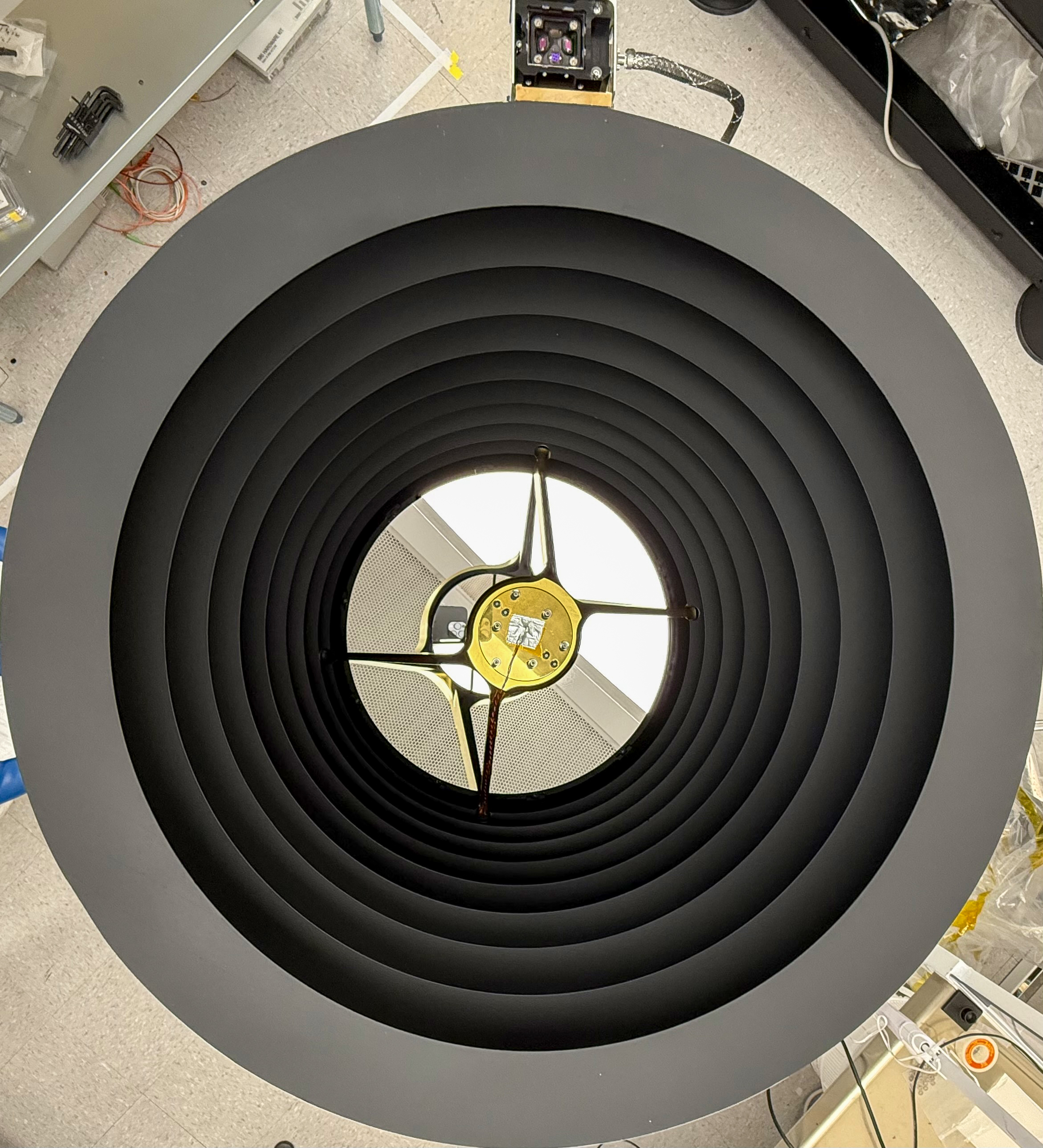

A rendering of Blue Origin’s proposed Lunar Transporter. Credit: Blue Origin

The documents Ars has reviewed do not contain some crucial information. For example, what are the “transfer stages” they refer to? Are they the Lunar Transporter, a reusable space tug, under development? Or a modified upper stage of New Glenn or something else? It’s also unclear whether the Blue Moon MK2-IL is more like the simpler MK1 lander (which should fly soon) or if it will require major development work. Ars put these and other questions to Blue Origin, which declined to comment for this article.

So what to make of all this?

Sources indicated that Blue Origin is moving aggressively forward on its lunar program. This is one reason why the company recently iced its New Shepard spacecraft and has curtailed other activities to increase focus on major goals, including ramping up New Glenn cadence and accelerating lunar plans. This new architecture is one result of that.

There are major steps to go. The company must demonstrate the Blue Moon vehicle with the uncrewed MK1 mission, which likely will launch sometime late this spring or during the summer, with a lunar landing to follow. And although there is no orbital refueling as part of this new plan, it still requires complex docking and deep-space maneuvers, which Blue Origin has no experience with. Whether Bezos’ company could pull off all of these challenging tasks before 2030 is far from certain.

But one thing is clear. The 21st century space race back to the Moon now includes three participants: China’s state-run program, SpaceX, and Blue Origin. Game on.

Eric Berger is the senior space editor at Ars Technica, covering everything from astronomy to private space to NASA policy, and author of two books: Liftoff, about the rise of SpaceX; and Reentry, on the development of the Falcon 9 rocket and Dragon. A certified meteorologist, Eric lives in Houston.

Why is Bezos trolling Musk on X with turtle pics? Because he has a new Moon plan. Read More »