Here’s how a satellite ended up as a ghostly apparition on Google Earth

Regardless of the identity of the satellite, this image is remarkable for several reasons.

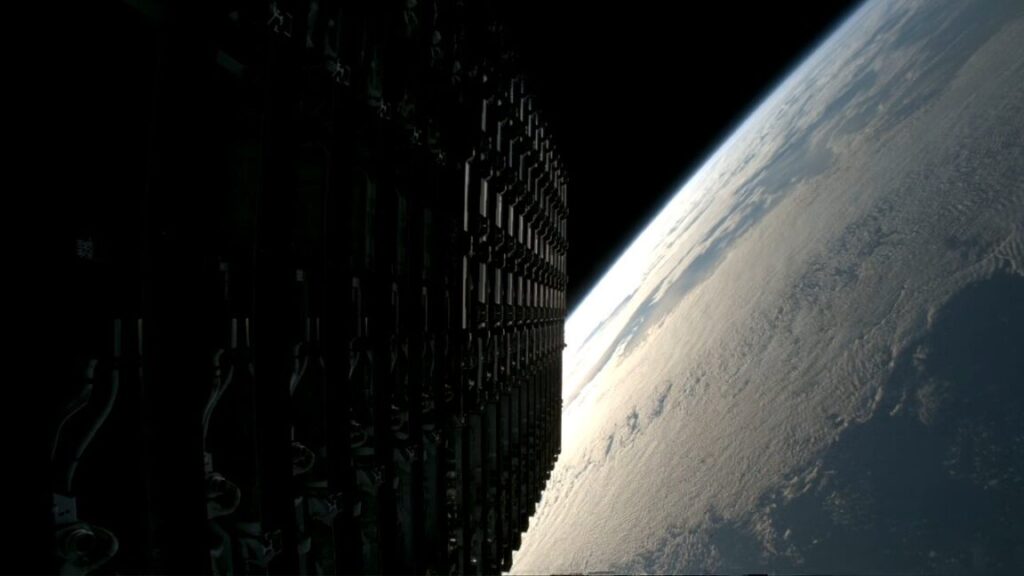

First, despite so many satellites flying in space, it’s still rare to see a real picture—not just an artist’s illustration—of what one actually looks like in orbit. For example, SpaceX has released photos of Starlink satellites in launch configuration, where dozens of the spacecraft are stacked together to fit inside the payload compartment of the Falcon 9 rocket. But there are fewer well-resolved views of a satellite in its operational environment, with solar arrays extended like the wings of a bird.

This is changing as commercial companies place more and more imaging satellites in orbit. Several companies provide “non-Earth imaging” services by repurposing Earth observation cameras to view other objects in space. These views can reveal information that can be useful in military or corporate espionage.

Secondly, the Google Earth capture offers a tangible depiction of a satellite’s speed. An object in low-Earth orbit must travel at more than 17,000 mph (more than 27,000 km per hour) to keep from falling back into the atmosphere.

While the B-2’s motion caused it to appear a little smeared in the Google Earth image a few years ago, the satellite’s velocity created a different artifact. The satellite appears five times in different colors, which tells us something about how the image was made. Airbus’ Pleiades satellites take pictures in multiple spectral bands: blue, green, red, panchromatic, and near-infrared.

At lower left, the black outline of the satellite is the near-infrared capture. Moving up, you can see the satellite in red, blue, and green, followed by the panchromatic, or black-and-white, snapshot with the sharpest resolution. Typically, the Pleiades satellites record these images a split-second apart and combine the colors to generate an accurate representation of what the human eye might see. But this doesn’t work so well for a target moving at nearly 5 miles per second.

Here’s how a satellite ended up as a ghostly apparition on Google Earth Read More »