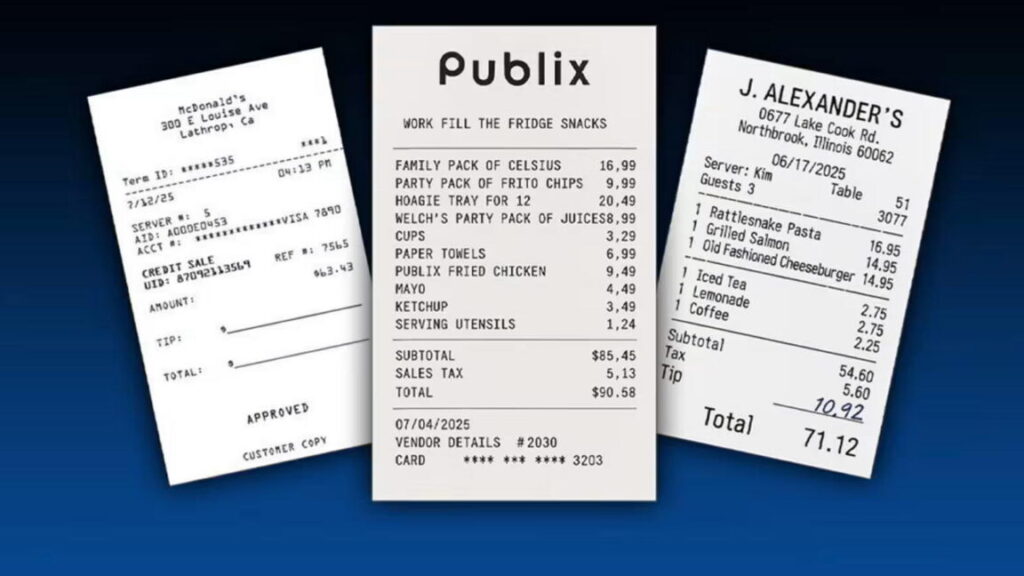

New image-generating AIs are being used for fake expense reports

Several receipts shown to the FT by expense management platforms demonstrated the realistic nature of the images, which included wrinkles in paper, detailed itemization that matched real-life menus, and signatures.

“This isn’t a future threat; it’s already happening. While currently only a small percentage of non-compliant receipts are AI-generated, this is only going to grow,” said Sebastien Marchon, chief executive of Rydoo, an expense management platform.

The rise in these more realistic copies has led companies to turn to AI to help detect fake receipts, as most are too convincing to be found by human reviewers.

The software works by scanning receipts to check the metadata of the image to discover whether an AI platform created it. However, this can be easily removed by users taking a photo or a screenshot of the picture.

To combat this, it also considers other contextual information by examining details such as repetition in server names and times and broader information about the employee’s trip.

“The tech can look at everything with high details of focus and attention that humans, after a period of time, things fall through the cracks, they are human,” added Calvin Lee, senior director of product management at Ramp.

Research by SAP in July found that nearly 70 percent of chief financial officers believed their employees were using AI to attempt to falsify travel expenses or receipts, with about 10 percent adding they are certain it has happened in their company.

Mason Wilder, research director at the Association of Certified Fraud Examiners, said AI-generated fraudulent receipts were a “significant issue for organizations.”

He added: “There is zero barrier for entry for people to do this. You don’t need any kind of technological skills or aptitude like you maybe would have needed five years ago using Photoshop.”

© 2025 The Financial Times Ltd. All rights reserved. Not to be redistributed, copied, or modified in any way.

New image-generating AIs are being used for fake expense reports Read More »