In trial, people lost twice as much weight by ditching ultraprocessed food

In a small randomized controlled trial, people lost twice as much weight when their diet was limited to minimally processed food compared to when they switched to a diet that included ultraprocessed versions of foods but was otherwise nutritionally matched.

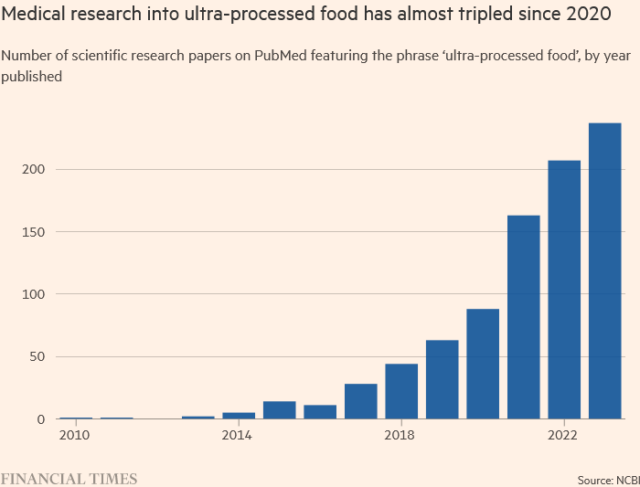

The trial, published in Nature Medicine by researchers at University College London, adds to a growing body of evidence that food processing, in addition to simple nutrition content, influences our weight and health. Ultraprocessed foods have already been vilified for their link to obesity—largely through weaker observational studies—but researchers have struggled to shore up the connection with high-quality studies and understand their impact on health.

The ultraprocessed foods researchers provided in the new trial were relatively healthy ones—as ultraprocessed foods go. They included things like multigrain breakfast cereal, packaged granola bars, flavored yogurt cups, fruit snacks, commercially premade chicken sandwiches, instant noodles, and ready-made lasagna. But, in the minimally processed trial diet, participants received meals from a caterer rather than ones from a grocery store aisle. The diet included overnight oats with fresh fruit, plain yogurt with toasted oats and fruit, handmade fruit and nut bars, freshly made chicken salad, and from-scratch stir fry and spaghetti Bolognese.

While the level of processing differed between the diets, the large-scale nutrition content—fat, protein, carbohydrates, fiber—were similar, as was the proportions of fruits, vegetables, dairy, and starchy food. Overall, both diets adhered to the dietary guidance from the UK government, called the Eatwell Guide (EWG).

Diet processing

The trial had a crossover design, meaning that participants were randomly split to start out on either the ultraprocessed food (UPF) diet or the minimally processed food (MPF) diet. They stayed on their starter diet for eight weeks, then took a break, and switched to the other diet. For both diets, food was delivered directly to the participants’ homes. Participants ate what they wanted and, mostly, didn’t seem to cheat by sneaking other food, based on food diaries and reported adherence.

Fifty participants completed at least one diet, while 43 completed both diets. The participants were mostly women, with a mean age of 43, and all had a body mass index categorized as overweight or obesity. At the start of the trial, ultraprocessed foods made up, on average, nearly 70 percent of the participants’ standard diets, and they were not adhering to the EWG recommendations.

In trial, people lost twice as much weight by ditching ultraprocessed food Read More »