After mice drink raw H5N1 milk, bird flu virus riddles their organs

Deadly dairy —

No, really, drinking raw milk during the H5N1 outbreak is a bad idea.

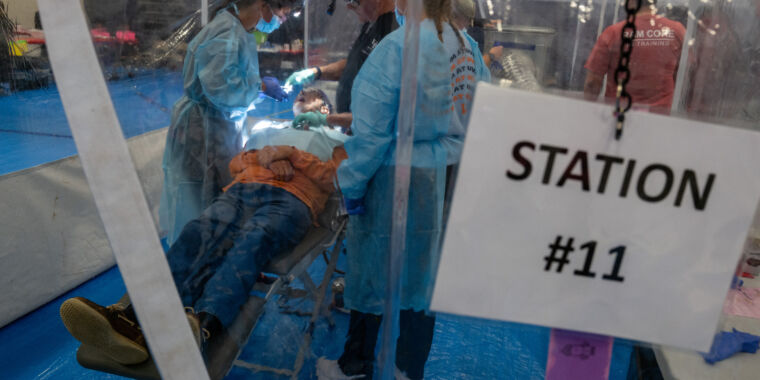

Enlarge / Fresh raw milk being poured into a container on a dairy farm on July 29, 2023, in De Lutte, Netherlands.

Despite the delusions of the raw milk crowd, drinking unpasteurized milk brimming with infectious avian H5N1 influenza virus is a very bad idea, according to freshly squeezed data published Friday in the New England Journal of Medicine.

Researchers at the University of Wisconsin-Madison squirted raw H5N1-containing milk from infected cows into the throats of anesthetized laboratory mice, finding that the virus caused systemic infections after the mice were observed swallowing the dose. The illnesses began quickly, with symptoms of lethargy and ruffled fur starting on day 1. On day 4, the animals were euthanized to prevent extended suffering. Subsequent analysis found that the mice had high levels of H5N1 bird flu virus in their respiratory tracts, as well their hearts, kidneys, spleens, livers, mammary glands, and brains.

“Collectively, our data indicate that HPAI [Highly Pathogenic Avian Influenza] A(H5N1) virus in untreated milk can infect susceptible animals that consume it,” the researchers concluded. The researchers also found that raw milk containing H5N1 can remain infectious for weeks when stored at refrigerator temperatures.

Bird flu has not historically been considered a foodborne pathogen, but prior to the unexpected outbreak of H5N1 in US dairy cows discovered in March, it had never been found at high levels in a food product like milk before. While experts have stepped up warnings against drinking raw milk amid the outbreak, the mouse experiment offers some of the first data on the risks of H5N1 from drinking unpasteurized dairy.

Before the mouse data, numerous reports have noted carnivores falling ill with H5N1 after eating infected wild birds. And a study from March in the journal Emerging Infectious Diseases reported that over half of the 24 or so cats on an H5N1-infected dairy farm in Texas died after drinking raw milk from the sick cows. Before their deaths, the cats displayed distressing neurological symptoms, and studies found the virus had invaded their lungs, brains, hearts, and eyes.

While the data cannot definitely determine if humans who drink H5N1-contaminated raw milk will suffer the same fate as the mice and cats, it highlights the very real risk. Still, raw milk enthusiasts have disregarded the concerns. PBS NewsHour reported last week that since March 25, when the H5N1 outbreak in US dairy cows was announced, weekly sales of raw cow’s milk have ticked up 21 percent, to as much as 65 percent compared with the same periods a year ago, according to data shared by market research firm NielsenIQ. Moreover, the founder of California-based Raw Milk Institute, Mark McAfee, told the Los Angeles Times this month that his customers baselessly believe drinking H5N1 will give them immunity to the deadly pathogen.

In normal times, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the Food and Drug Administration strongly discourage drinking raw milk. Without pasteurization, it can easily be contaminated with a wide variety of pathogens, including Campylobacter, Cryptosporidium, E. coli, Listeria, Brucella, and Salmonella.

Fortunately, for the bulk of Americans who heed germ theory, pasteurization appears completely effective at deactivating the virus in milk, according to thorough testing by the FDA. Pasteurized milk is considered safe during the outbreak. The US Department of Agriculture, meanwhile, reports finding no H5N1 in retail beef so far and, in laboratory experiments, beef patties purposefully inoculated with H5N1 had no viable virus in them after the patties were cooked to 145°F (medium) or 160°F (well done).

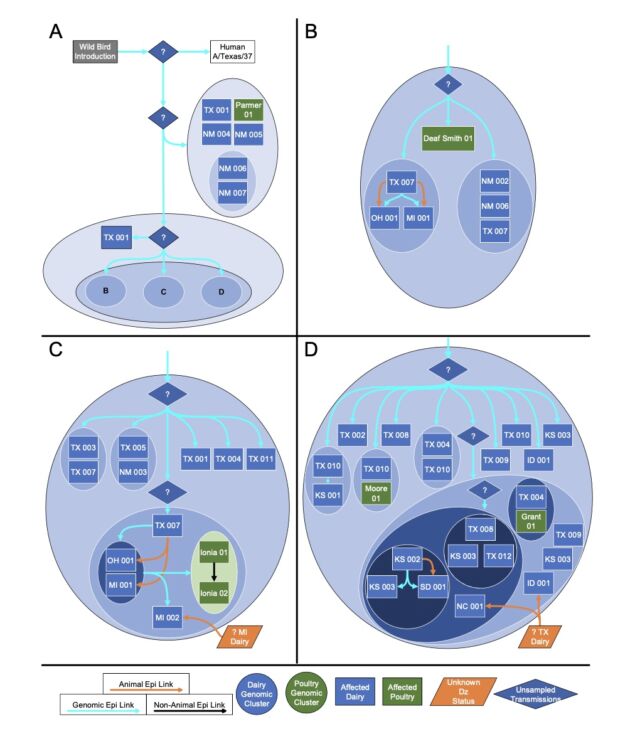

To date, the USDA has reported that H5N1 has infected at least 58 dairy herds in nine states.

After mice drink raw H5N1 milk, bird flu virus riddles their organs Read More »