“Windows 11 26H1” is a special version of Windows exclusively for new Arm PCs

But for app developers, IT shops, and anyone else who needs to test things against multiple Windows versions at once, it does create an odd period of overlap where they’ll need to account for one version of Windows that runs just on these brand-new PCs, and one version of Windows that covers everybody else.

Special treatment for Arm PCs

Releasing a new version of Windows that just covers new Arm PCs is another signal of Microsoft’s commitment to Arm processors and the Arm version of Windows, after decades of near-exclusive focus on the x86 version of the OS that ran on Intel and AMD’s chips.

Microsoft offered multiple versions of both Windows 10 and Windows 11 in both x86 and Arm editions, but the 24H2 update was a major milestone for Arm PCs. It came with big under-the-hood changes to Windows’ compiler, kernel, and scheduler, and an optimized x86-to-Arm translation layer called Prism that enhanced the compatibility and performance of apps that hadn’t been built to run on Arm processors.

The 24H2 update also coincided with the release of the first-generation Qualcomm Snapdragon X-series processors, high-performance Arm chips developed by some of the same people behind Apple’s M-series chips for Macs. Many third-party developers have also finally released Arm-native versions of their Windows apps, which are faster and more responsive than translated x86 apps.

Microsoft’s confidence in the Arm version of Windows was so great that the new Surface PCs released in mid-2024 used Qualcomm’s processors exclusively, relegating Intel chips to offshoot versions for businesses with strict compatibility requirements. For years previously, Microsoft had treated the Intel- and AMD-based Surfaces as the “main” ones and the Arm-based Surface Pro X as the offshoot.

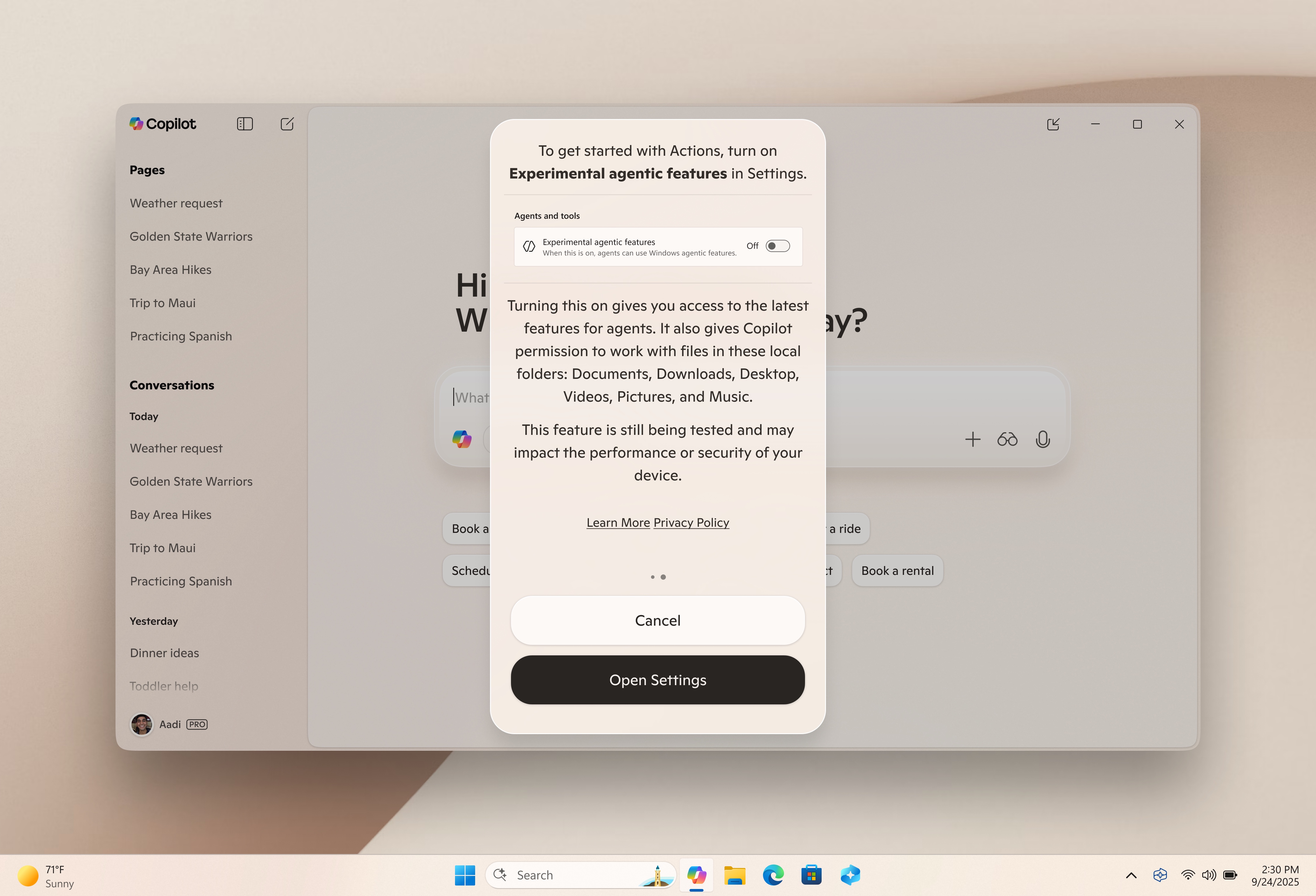

Since the 24H2 update, development on the Arm and the traditional x86 versions of Windows has happened at slightly different rates. Some features, particularly things like Recall and Click To Do that were only rolling out to Copilot+ PCs with fast built-in neural processing units (NPUs), have been available for the Arm versions of Windows for a few weeks or months before they hit the x86 versions. Windows 11 24H2 itself was also shipping on Arm PCs in stores several months before Microsoft began rolling the update out to the wider PC ecosystem.

We’ve asked Microsoft to elaborate on what the Windows 11 26H1 update includes and whether it contains any changes that will benefit the wider PC ecosystem somewhere down the line. We’ll update the article if we receive a response.

“Windows 11 26H1” is a special version of Windows exclusively for new Arm PCs Read More »