Fanfic community craves familiarity much more than novelty—but reports greater enjoyment from novelty.

Credit: Aurich Lawson | Marvel

It’s widely accepted conventional wisdom that when it comes to creative works—TV shows, films, music, books—consumers crave an optimal balance between novelty and familiarity. What we choose to consume and share with others, in turn, drives cultural evolution.

But what if that conventional wisdom is wrong? An analysis based on data from a massive online fan fiction (fanfic) archive contradicts this so-called “balance theory,” according to a paper published in the journal Humanities and Social Sciences Communications. The fanfic community seems to overwhelmingly prefer more of the same, consistently choosing familiarity over novelty; however, they reported greater overall enjoyment when they took a chance and read something more novel. In short: “Sameness entices, but novelty enchants.”

Strictly speaking, authors have always copied characters and plots from other works (cf. many of William Shakespeare’s plays), although the advent of copyright law complicated matters. Modern fan fiction as we currently think of it arguably emerged with the 1967 publication of the first Star Trek fanzine (Spockanalia), which included spinoff fiction based on the series. Star Trek also spawned the subgenre of slash fiction, when writers began creating stories featuring Kirk and Spock (Kirk/Spock, or K/S) in a romantic (often sexual) relationship.

The advent of the World Wide Web brought fan fiction to the masses, starting with Usenet newsgroups and mailing lists and eventually the development of massive online archives where creators could upload their work to be read and commented upon by readers. The subculture has since exploded; there’s fanfic based on everything from Sherlock Holmes to The X-Files, Buffy the Vampire Slayer, Game of Thrones, the Marvel Cinematic Universe, and Harry Potter. You name it, there’s probably fanfic about it.

There are also many subgenres within fanfic beyond slash, some of them rather weird, like a magical pregnancy (Mpreg) story in which Sherlock Holmes and Watson fall so much in love with each other that one of them becomes magically pregnant. (One suspects Sherlock would not handle morning sickness very well.) Sometimes fanfic even breaks into the cultural mainstream: E.L. James’ bestselling Fifty Shades of Grey started out as fan fiction set in the world of Stephenie Meyer’s Twilight series.

So fanfic is a genuine cultural phenomenon—hence its fascination for Simon DeDeo, a complexity scientist at Carnegie Mellon University and the Santa Fe Institute who studies cultural evolution and the emergence of social hierarchies. (I reported on DeDeo’s work analyzing the archives of London’s Old Bailey in 2014.) While opinion remains split—even among the authors of the original works—as to whether fanfic is a welcome homage to the original works that just might help drive book sales or whether it constitutes a form of copyright infringement, DeDeo enthusiastically embraces the format.

“It’s the dark matter of creativity,” DeDeo told Ars. “I love that it exists. It’s a very non-elitist form. There’s no New York Times bestseller list. It would be hard to name the most famous fan fiction writers. The world building has been done. The characters exist. The plot elements have already been put together. So the bar to entry is lower. Maybe sometime in the 19th century we get a notion of genius and the individual creator, but that’s not really what storytelling has been about for the majority of human history. In that one sense, fan fiction is closer to what we were doing around the campfire.”

Star Trek arguably spawned contemporary fan fiction—including stories imagining Kirk and Spock as romantic partners. Credit: Paramount Pictures

That’s a boon for fanfic writers, most of whom have non-creative day jobs; fanfic provides them with a creative outlet. Every year, when DeDeo asks students in his classes whether they read and/or write fanfic, a significant percentage always raise their hands. (He once asked a woman about why she wrote slash. Her response: “Because no one was writing porn that I wanted to read.”) In fact, that’s how this current study came about. Co-author Elise Jing is one of DeDeo’s former students with a background in both science and the humanities—and she’s also a fanfic connoisseur.

Give them more of the same

Jing thought (and DeDeo concurred) that the fanfic subculture provided an excellent laboratory for studying cultural evolution. “It’s tough to get students to read a book. They write fan fiction voluntarily. This is stuff they care about writing and care about reading. Nobody gets prestige or power in the larger society from writing fan fiction,” said DeDeo. “This is not a top-down model where Hollywood is producing something and then the fans are consuming it. The fans are producing and consuming so it’s a truly self-contained culture that’s constantly evolving. It’s a pure product consumption cycle. People read it, they bookmark it, they write comments on it, and all that gives us insight into how it’s being received. If you’re a psychologist, you couldn’t pay to get this kind of data.”

Fanfic is a tightly controlled ecosystem, so it lacks many of the confounding factors that make it so difficult to study mainstream cultural works. Also, the fan fiction community is enormous, so the potential datasets are huge. For this study, the authors relied on data from the online Archive of Our Own (AO3), which boasts nearly 9 million users covering more than 70,000 different fandoms and some 15 million individual works. (Sadly, the site has since shut down access to its data over concerns of that data being used to train AI.)

According to DeDeo, the idea was to examine the question of cultural evolution on a population level, rather than on the individual level: “How do these individual things agglomerate to produce the culture? “

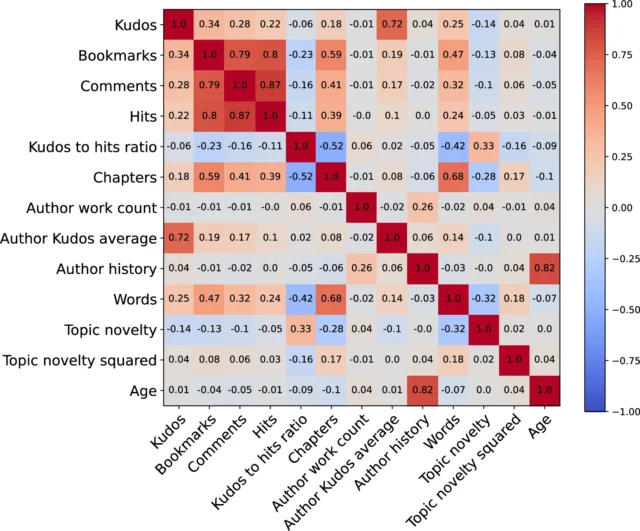

Strong positive correlation is found between the response variables except for the Kudos-to-hits ratio. Topic novelty is weakly positively correlated with Kudos-to-hits ratio but negatively correlated with the other response variables. Credit: E. Jing et al., 2025

The results were striking. AO3 members overwhelmingly preferred familiarity in their fan fiction, i.e., more of the same. One notable exception was a short story that was both hugely popular and highly novel. Simply titled “I Am Groot,” the story featured the character from Guardians of the Galaxy. The text is just “I am Groot” repeated 40,000 times—a stroke of genius in that this is entirely consistent with the canonical MCU character, whose entire dialogue consists of those words, with meaning conveyed by shifts of tone and context. But such exceptions proved to be very rare.

“We were so stunned that balance theory wasn’t working,” said DeDeo, who credits Jing with the realization that they were dealing with two distinct pieces of the puzzle: how much is being consumed, and how much people like what they consume, i.e., enjoyment. Their analysis revealed, first, that people really don’t want an optimized mix of familiar and new; they want the same thing over and over again, even within the fanfic community. But when people do make the effort to try something new, they tend to enjoy it more than just consuming more of the same.

In short, “We are anti-balance theory,” said DeDeo. “In biology, for example, you make a small variation in the species and you get micro-evolution. In culture, a minor variation is just less likely to be consumed. So it really is a mystery how we evolve at all culturally; it’s not happening by gradual movement. We can see that there’s novelty. We can see that when people encounter novelty, they enjoy it. But we can’t quite make sense of how these two competing effects work out.”

“This is the great paradox,” said DeDeo. “Culture has to be stable. Without long-term stability, there’s no coherent body of work that can even constitute of culture if every year fan fiction totally changes. That inherent cultural conservatism is in some sense a precondition for culture to exist at all.” Yet culture does evolve, even within the fanfic community.

One possible alternative is some kind of punctuated equilibrium model for cultural evolution, in which things remain stable but undergo occasional leaps forward. “One story about how culture evolves is that eventually, the stuff that’s more enjoyable than what people keep re-consuming somehow becomes accessible to the majority of the community,” said DeDeo. “Novelty might act as a gravitational pull on the center and [over time] some new material gets incorporated into the culture.” He draws an analogy to established tech companies like IBM versus startups, most of which die out; but those few that succeed often push the culture substantially forward.

Perhaps there are two distinct groups of people: those who actively seek out new things and those who routinely click on familiar subject matter because even though their enjoyment might be less, it’s not worth overcoming their inertia to try out something new. Perhaps it is those who seek novelty that sow the seeds of eventual shifts in trends.

“Is it that we’re tired? Is it that we’re lazy? Is this a conflict within a human or within a culture?” said DeDeo. “We don’t know because we only get the raw numbers. If we could track an individual reader to see how they moved between these two spaces, that would be really interesting.”

Humanities and Social Sciences Communications, 2025. DOI: 10.1057/s41599-025-05166-3 (About DOIs).

Jennifer is a senior writer at Ars Technica with a particular focus on where science meets culture, covering everything from physics and related interdisciplinary topics to her favorite films and TV series. Jennifer lives in Baltimore with her spouse, physicist Sean M. Carroll, and their two cats, Ariel and Caliban.