Google brings new Gemini features to Chromebooks, debuts first on-device AI

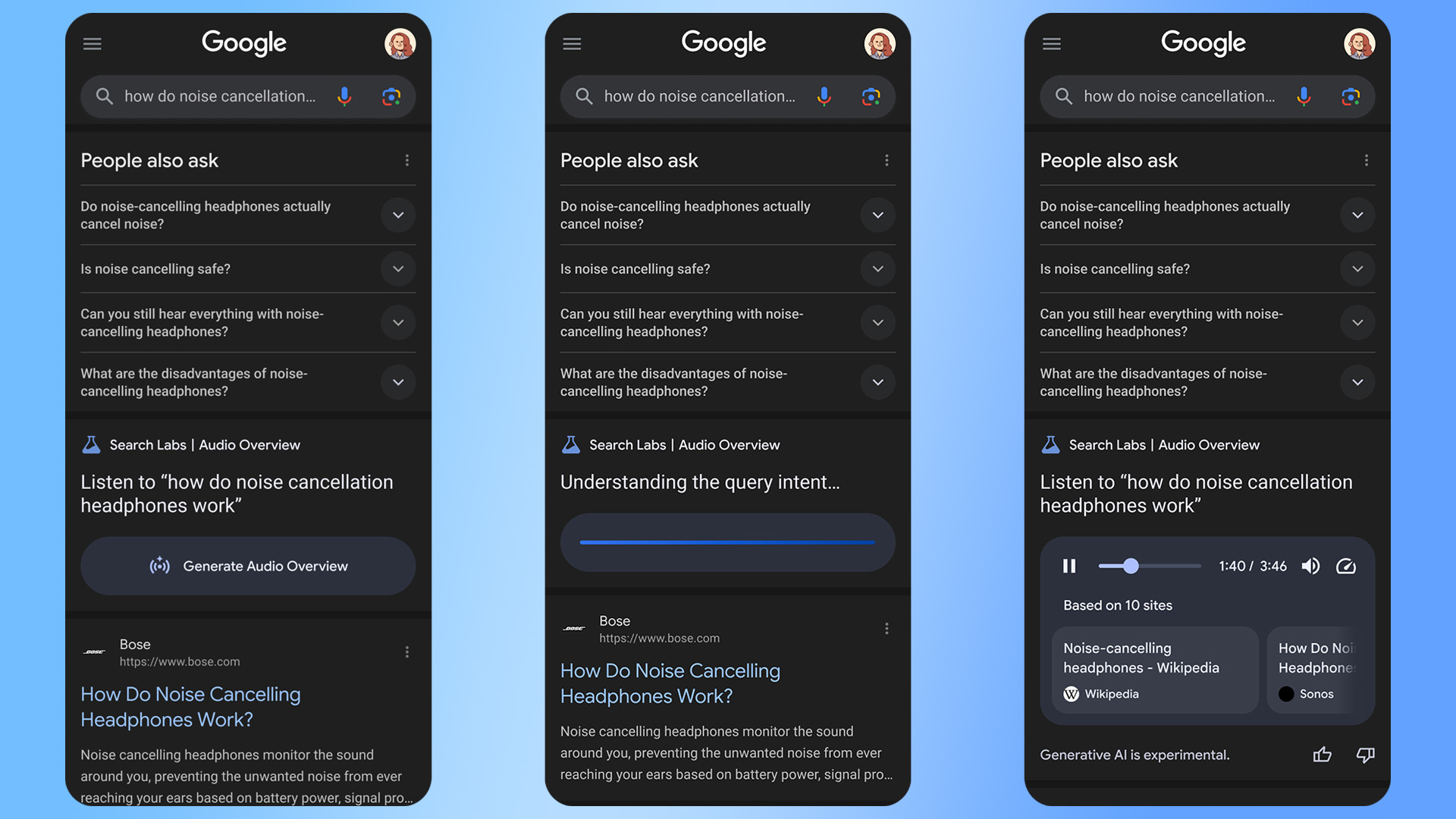

Google hasn’t been talking about Chromebooks as much since AI became its all-consuming focus, but that’s changing today with a bounty of new AI features for Google-powered laptops. Newer, more powerful Chromebooks will soon have image generation, text summarization, and more built into the OS. There’s also a new Lenovo Chromebook with a few exclusive AI goodies that only work thanks to its overpowered hardware.

If you have a Chromebook Plus device, which requires a modern CPU and at least 8GB of RAM, your machine will soon get a collection of features you may recognize from other Google products. For example, Lens is expanding on Chrome OS, allowing you to long-press the launcher icon to select any area of the screen to perform a visual search. Lens also includes text capture and integration with Google Calendar and Docs.

Gemini models are also playing a role here, according to Google. The Quick Insert key, which debuted last year, is gaining a new visual element. It could already insert photos or emoji with ease, but it can now also help you generate a new image on demand with AI.

Google’s new Chromebook AI features.

Even though Google’s AI features are running in the cloud, the AI additions are limited to this more powerful class of Google-powered laptops. The Help Me Read feature leverages Gemini to summarize long documents and webpages, and it can now distill that data into a more basic form. The new Summarize option can turn dense, technical text into something more readable in a few clicks.

Google has also rolled out a new AI trial for Chromebook Plus devices. If you buy one of these premium Chromebooks, you’ll get a 12-month free trial of the Google AI Pro plan, which gives you 2TB of cloud storage, expanded access to Google’s Gemini Pro model, and NotebookLM Pro. NotebookLM is also getting a place in the Chrome OS shelf.

Google brings new Gemini features to Chromebooks, debuts first on-device AI Read More »