“Million-year-old” fossil skulls from China are far older—and not Denisovans

careful with that, it’s an antique

The revised age may help make sense of 2-million-year-old stone tools elsewhere in China.

Two skulls from Yunxian, in northern China, aren’t ancestors of Denisovans after all; they’re actually the oldest known Homo erectus fossils in eastern Asia.

A recent study has re-dated the skulls to about 1.77 million years old, which makes them the oldest hominin remains found so far in East Asia. Their age means that Homo erectus (an extinct common ancestor of our species, Neanderthals, and Denisovans) must have spread across the continent much earlier and much faster than we’d previously given them credit for. It also sheds new light on who was making stone tools at some even older archaeological sites in China.

Homo erectus spread like wildfire

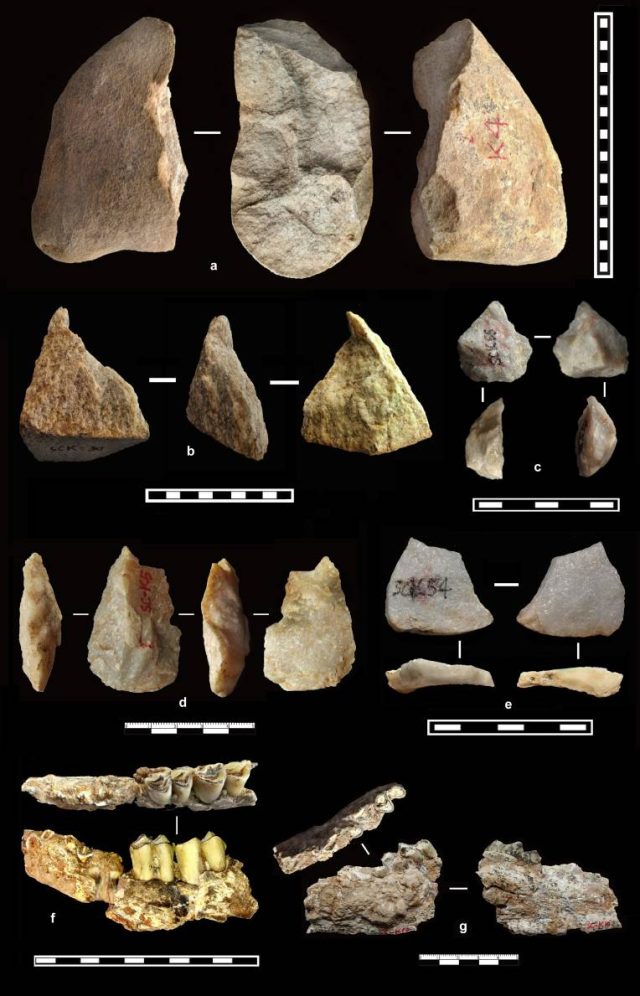

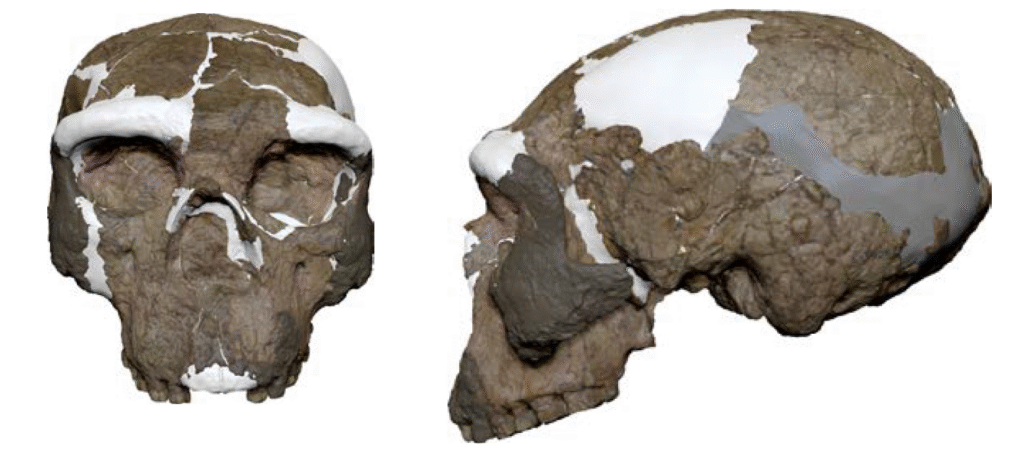

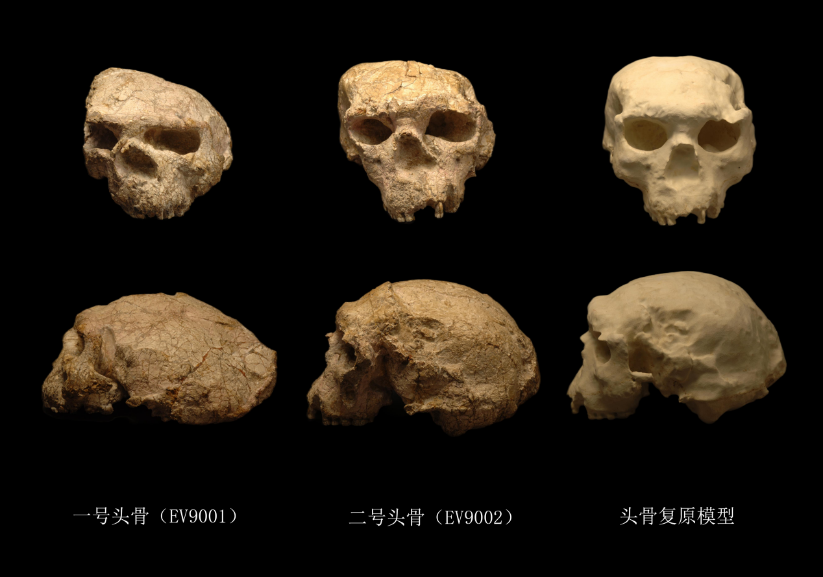

Yunxian is an important—and occasionally contentious—archaeological site on the banks of central China’s Han River. Along with hundreds of stone tools and animal bones, the layers of river sediment have yielded three nearly complete hominin skulls (only two of which have been described in a publication so far). Shantou University paleoanthropologist Hua Tu and his colleagues measured the ratio of two isotopes, aluminum-26 and beryllium-10, in grains of quartz from the sediment layer that once held the skulls. The results suggest that Homo erectus lived and died along the Han River 1.77 million years ago. That’s just 130,000 years after the species first appeared in Africa.

(Side note: This river has been depositing layers of silt and gravel on the same terraces for at least 2 million years, and that’s just extremely cool.)

The revised date suggests that Homo erectus spread across Asia much more quickly than anthropologists had realized. So far, the oldest hominin bones found anywhere outside Africa are five skulls, along with hundreds of other bones, from Dmanisi Cave in Georgia. The Dmanisi bones are between 1.85 million and 1.77 million years old, and they (probably—more on that below) also belong to Homo erectus.

Until recently, the next-oldest Homo erectus fossils outside Africa were the 1.63-million-year-old fossils from another Chinese site, Gongwangling, a short distance north of Yunxian. (That’s not counting a couple of teeth from a site in southern China with an age that is a little less certain.) Those dates had suggested Homo erectus seemed to have taken a leisurely 140,000 years to spread east into Asia. But it now looks like hominins were living in Georgia and central China at about the same time, which means they spread out very fast, started earlier than we knew, or both.

The Homo longi and short of it

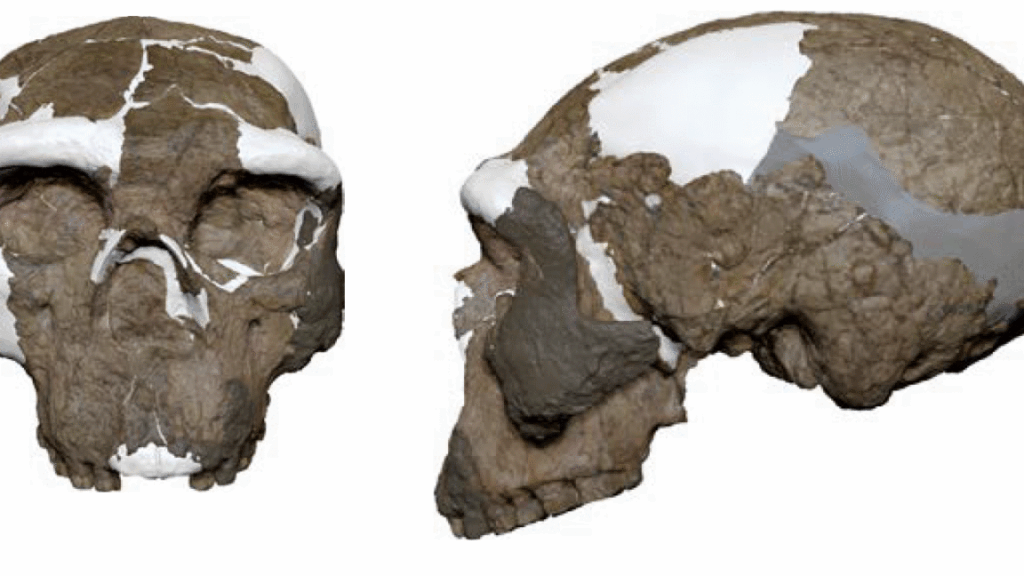

All of this means that the Yunxian skulls are probably not—as a September 2025 study claimed—close ancestors of the enigmatic Denisovans. The authors of that paper had digitally reconstructed one of the skulls and concluded that it looked a lot like a 146,000-year-old skull from Harbin, China (which a recent DNA study identified as a Denisovan, also known as Homo longi).

The researchers had argued that the original owners of the Yunxian skulls had lived not long after the Denisovan/Homo longi branch of the hominin family tree split off from ours—in other words, that the Yunxian skulls weren’t mere Homo erectus but early Homo longi, close cousins of our own species. Using the original paleomagnetic dates for the Yunxian skulls, that study’s authors drew up a hominin family tree in which our species and Denisovans are more closely related to each other than either is to Neanderthals—one in which the branching happened much earlier than DNA evidence suggests.

There were many issues with those arguments, but the revised age for the Yunxian skulls sounds like a death knell for them. “1.77 million years is just too old to be a credible connection to the Denisovan group, which DNA tells us got started after around 700,000 years ago,” University of Wisconsin paleoanthropologist John Hawks, who was not involved in the study, told Ars in an email.

But the most interesting thing about these skulls being 1.77 million years old is that the date provides a reference point for understanding even older sites in China—sites that may suggest that Homo erectus wasn’t even the first hominin to make it this far.

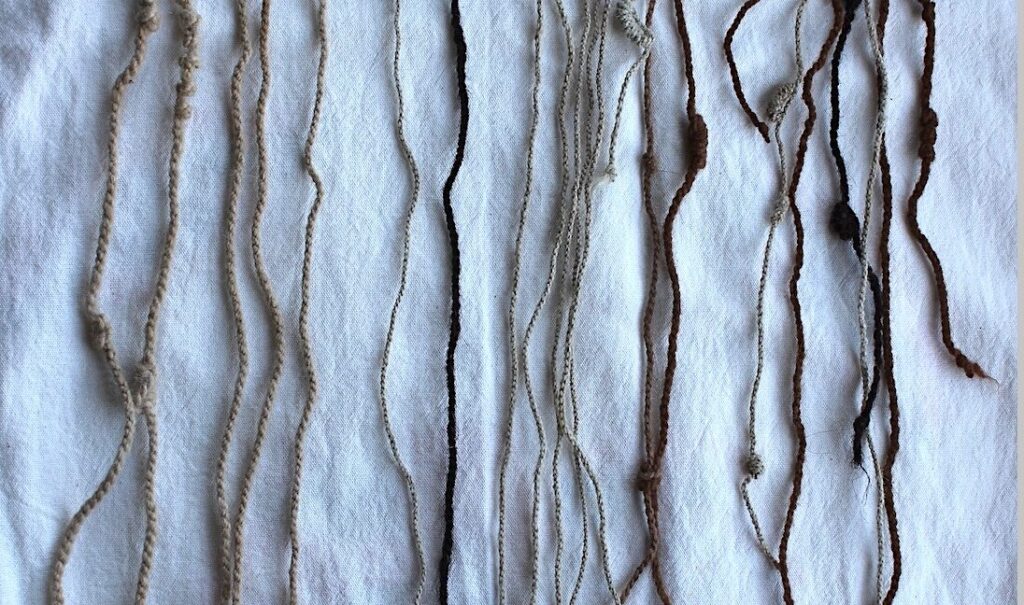

Stone tools collected from Shangchen, China. Credit: Prof. Zhaoyu Zhu

Out of Africa: The prequel

Homo erectus first shows up in the fossil record around 1.9 million years ago in Africa, where it’s sometimes also called Homo ergaster because paleoanthropologists seem to enjoy naming things and then arguing about those names for several decades. A few hundred thousand years later, Homo erectus showed up everywhere: from South Africa northward to the Levant and from Dmanisi Cave in Georgia eastward to the islands of Indonesia.

We typically think of Homo erectus as the first of our hominin ancestors to expand beyond Africa, along routes that our own species would retread 1.5 million years later. More to the point, many paleoanthropologists think of them as the first hominin that could have adapted to so many different environments, each with its own challenges, along the way.

But we may need to give earlier members of our genus, like Homo habilis, a little more credit because stone tools from two other sites in China seem to be older than Homo erectus. At Shangchen, a site on the southern edge of China’s Loess Plateau, archaeologists unearthed stone tools from a 2.1-million-year-old layer of sediment. And at the Xihoudu site in northern China, stone tools date to 2.43 million years ago.

“If you have a site in China that’s 2.43 million years, and the origin of Homo erectus is 1.9 million years ago, either you need to push the origin of Homo erectus back to 2.5 or 2.6 million years or we need to accept that we need to be looking at other hominins that may have actually moved out of Africa,” University of Hawai’i at Manoa paleoanthropologist Christopher Bae, a coauthor of the new study, told Ars.

So who made those 2-million-year-old tools?

Archaeologists have unearthed stone tools but no hominin fossils at both sites, making it difficult to say for sure who the toolmakers were. But if they weren’t Homo erectus, the next most likely suspects would be older members of our genus, like Homo habilis or Homo rudolfensis. That would mean hominin expansion “out of Africa” actually happened several times during the history of our genus: once with early Homo, again with Homo erectus, and yet again with our species.

“There could have been an earlier wave that died out or interbred, so there’s all kinds of possibilities open there,” Purdue University paleoanthropologist Darryl Granger, also a coauthor of the recent study, told Ars.

In fact, there’s some debate about whether the Dmanisi fossils actually belonged to Homo erectus proper. One thing the two dueling reconstructions of the Yunxian skulls agree on is that those hominins had flattish faces, more like ours—and like the 1.63-million-year-old Homo erectus skull from Gongwangling. But the Dmanisi hominins’ lower faces project dramatically forward, like those of older hominins.

Some paleoanthropologists classify the Dmanisi fossils as their own species, but others argue they’re more like early members of our genus, such as Homo habilis or Homo rudolfensis. Those earlier hominins may have been more capable of migrating and adapting than we’ve realized.

It’s still very clear, from both fossil and genetic evidence, that our species evolved in Africa and spread from there to the rest of the world. But it’s also increasingly clear that there were several other species of hominins in other places, doing other things, at least off and on, for a very long time before we showed up. Yunxian, and its revised age, could help anthropologists better understand part of that story.

“Actually being able to anchor the Homo erectus sites with firm, solid dates helps us try to reconfigure this model,” said Bae. “This is where Yunxian really plays a major role in this. Now that we’ve got older dates to anchor the Yunxian Homo erectus fossils, I think we can really bring in this discussion with Xihoudu and Shangchen.”

Time to dig deeper

The answers may still lie buried—maybe just a few meters below the fossil skulls and stone tools at sites like Yunxian and Gongwangling, in older sediment layers. Archaeologists may not have seen a reason to explore these, since no one lived in China before 1.7 million years ago. The age of the Yunxian skulls, along with the even older stone tools at Shangchen and Xihoudu, may warrant deeper digging.

“People haven’t been looking for artifacts and fossils in two-plus million-year-old sediments in these locations in China,” said Granger. “I can think of places that I would like to go back and look if I had more time and money.”

At other sites, researchers have already unearthed fossil animal bones from the same age range as China’s oldest stone tools, but paleoanthropologists haven’t double-checked whether any of those bones might belong to early hominins rather than other mammals. Bae said, “It’s just that they haven’t been receiving any attention, or not enough attention.”

Science Advances, 2026. DOI: 10.1126/sciadv.ady2270 About DOIs).

“Million-year-old” fossil skulls from China are far older—and not Denisovans Read More »