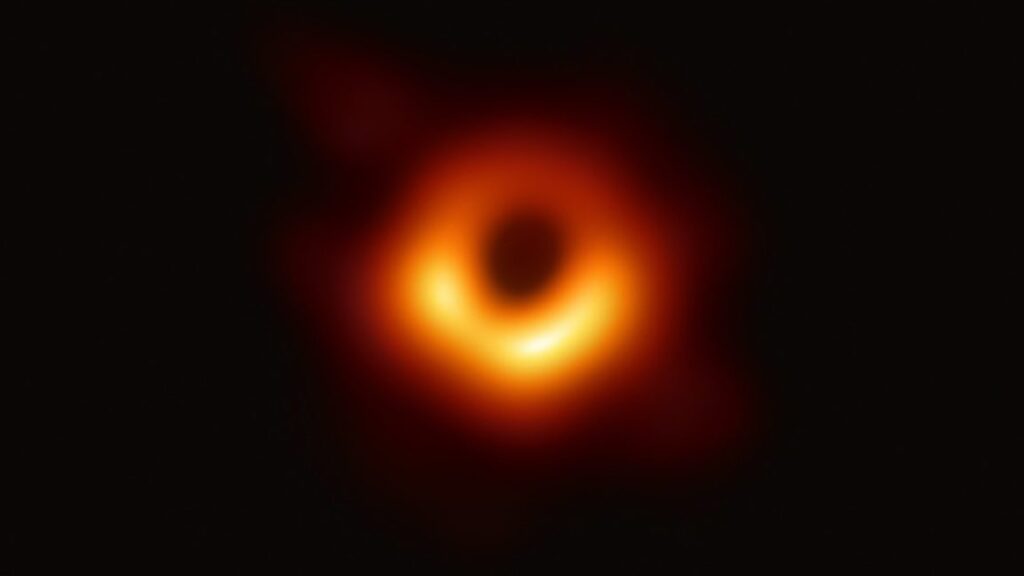

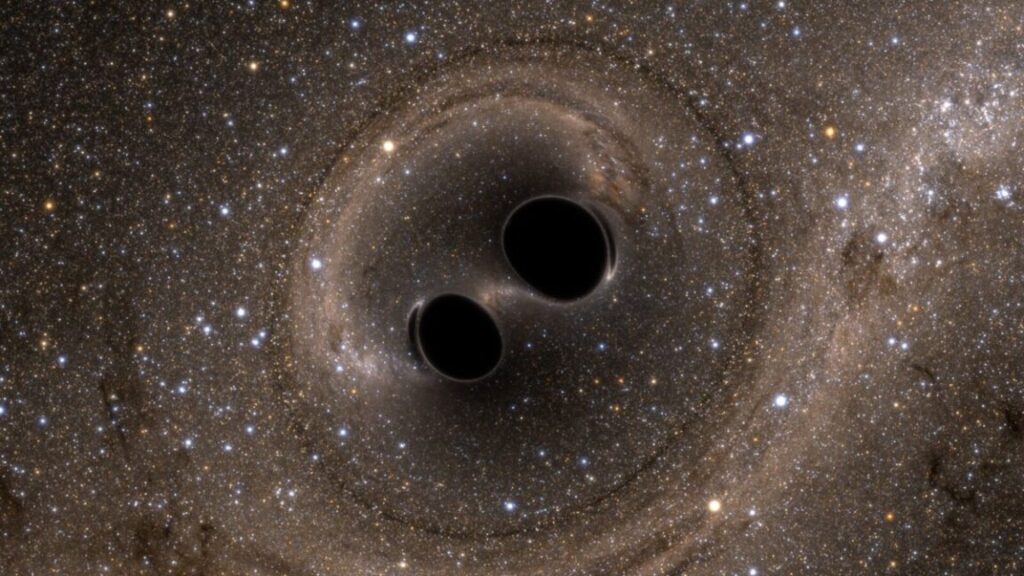

This black hole “burps” with Death Star energy

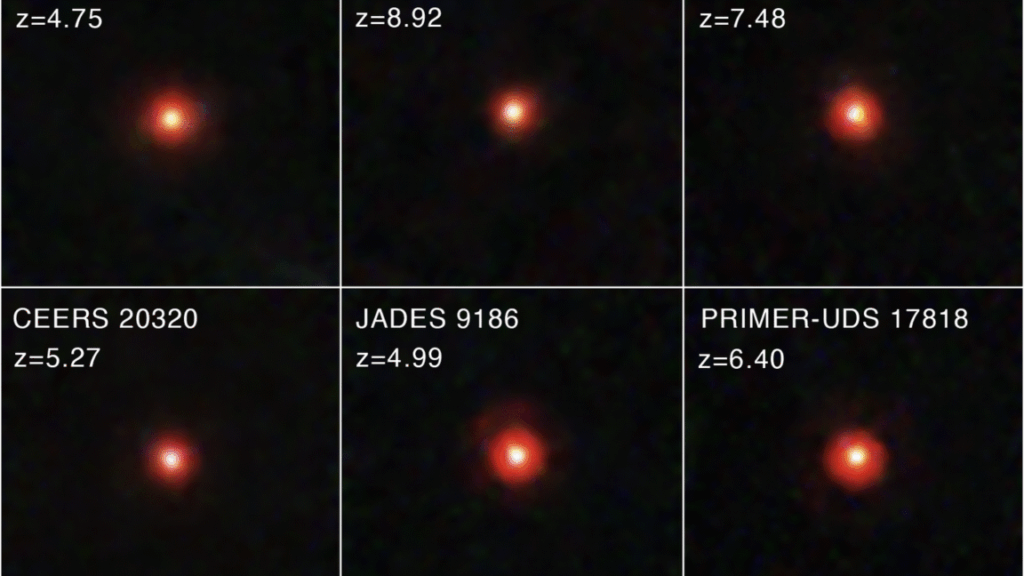

When AT2018hyz, aka “Jetty,” was first discovered, radio telescopes didn’t detect any signatures of an outflow emission of material within the first few months. According to Cendes, that’s true of some 80 percent of TDEs, so astronomers moved on, preferring to use precious telescope time for more potentially interesting objects. A few years later, radio data from the Very Large Array (VLA) showed that Jetty was lighting up the skies again, spewing out material at a whopping 1.4 millijansky at 5 GHz.

Since then, that brightness has kept increasing. Just how large is the increase? Well, people have estimated the fictional Death Star’s emitted energy in the Star Wars saga, and Jetty McJetface’s emissions are a trillion times more than that, perhaps as much as 100 trillion times the energy. As for why Jetty initially eluded detection, there seems to be a single jet emitting radiation in one direction that might not have been aimed at Earth. Astronomers should be able to confirm this once the energy peaks.

Cendes and her team are now scouring the skies for similar behavior in high-energy TDEs, since the existence of Jetty suggests that delayed outflow is more common than astronomers previously expected. It’s such an unprecedented phenomenon that astronomers haven’t really looked for them before. After all, “If you have an explosion, why would you expect there to be something years after the explosion happened when you didn’t see something before?” said Cendes.

DOI: Astrophysical Journal, 2026. 10.3847/1538-4357/ae286d (About DOIs).

This black hole “burps” with Death Star energy Read More »