The nine-armed octopus and the oddities of the cephalopod nervous system

A mix of autonomous and top-down control manage the octopus’s limbs.

With their quick-change camouflage and high level of intelligence, it’s not surprising that the public and scientific experts alike are fascinated by octopuses. Their abilities to recognize faces, solve puzzles, and learn behaviors from other octopuses make these animals a captivating study.

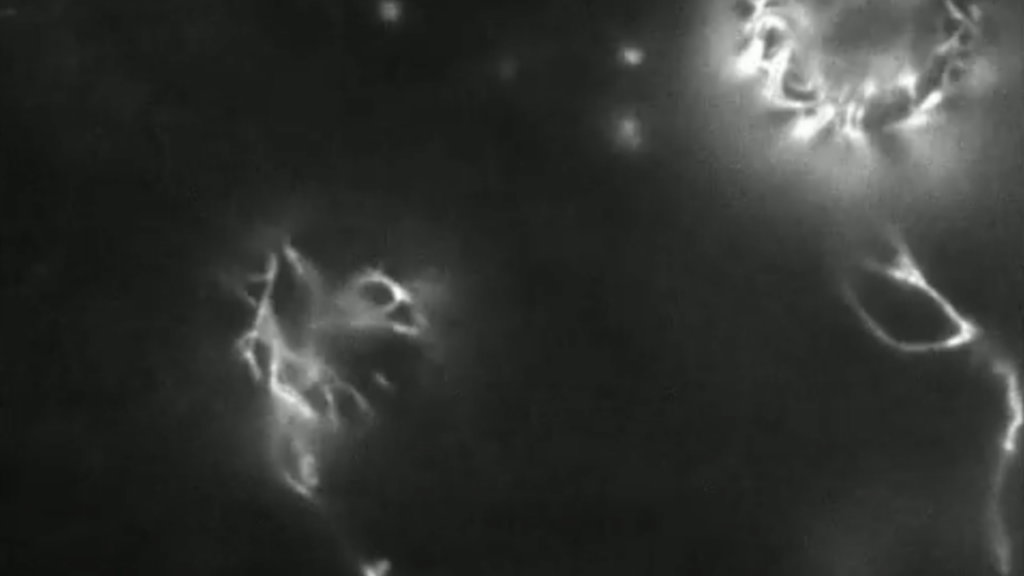

To perform these processes and others, like crawling or exploring, octopuses rely on their complex nervous system, one that has become a focus for neuroscientists. With about 500 million neurons—around the same number as dogs—octopuses’ nervous systems are the most complex of any invertebrate. But, unlike vertebrate organisms, the octopus’s nervous system is also decentralized, with around 350 million neurons, or 66 percent of it, located in its eight arms.

“This means each arm is capable of independently processing sensory input, initiating movement, and even executing complex behaviors—without direct instructions from the brain,” explains Galit Pelled, a professor of Mechanical Engineering, Radiology, and Neuroscience at Michigan State University who studies octopus neuroscience. “In essence, the arms have their own ‘mini-brains.’”

A decentralized nervous system is one factor that helps octopuses adapt to changes, such as injury or predation, as seen in the case of an Octopus vulgaris, or common octopus, that was observed with nine arms by researchers at the ECOBAR lab at the Institute of Marine Research in Spain between 2021 and 2022.

By studying outliers like this cephalopod, researchers can gain insight into how the animal’s detailed scaffolding of nerves changes and regrows over time, uncovering more about how octopuses have evolved over millennia in our oceans.

Brains, brains, and more brains

Because each arm of an octopus contains its own bundle of neurons, the limbs can operate semi-independently from the central brain, enabling faster responses since signals don’t always need to travel back and forth between the brain and the arms. In fact, Pelled and her team recently discovered that “neural signals recorded in the octopus arm can predict movement type within 100 milliseconds of stimulation, without central brain involvement.” She notes that “that level of localized autonomy is unprecedented in vertebrate systems.”

Though each limb moves on its own, the movements of the octopus’s body are smooth and conducted with a coordinated elegance that allows the animal to exhibit some of the broadest range of behaviors, adapting on the fly to changes in its surroundings.

“That means the octopus can react quickly to its environment, especially when exploring, hunting, or defending itself,” Pelled says. “For example, one arm can grab food while another is feeling around a rock, without needing permission from the brain. This setup also makes the octopus more resilient. If one arm is injured, the others still work just fine. And because so much decision-making happens at the arms, the central brain is freed up to focus on the bigger picture—like navigating or learning new tasks.”

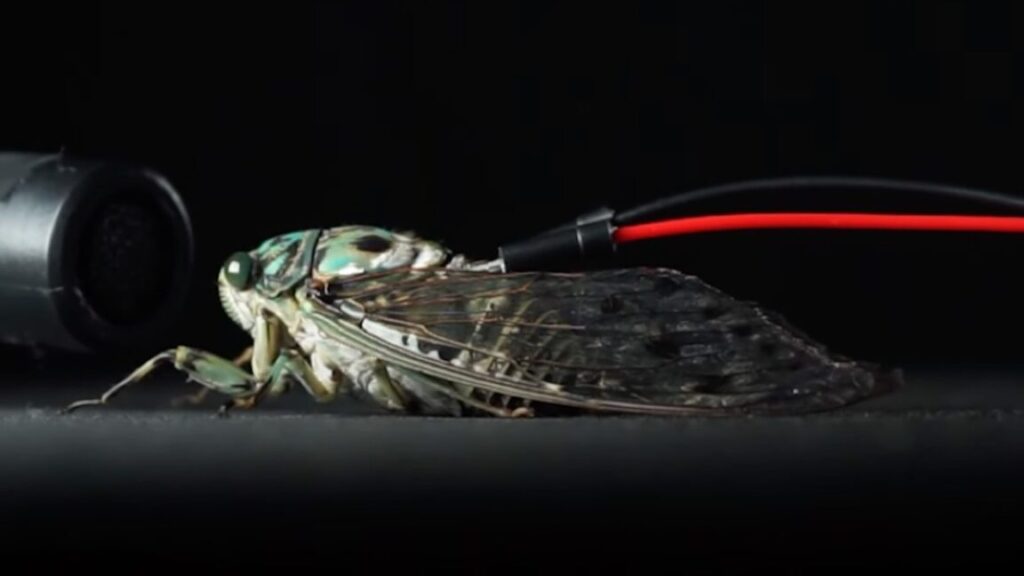

As if each limb weren’t already buzzing with neural activity, things get even more intricate when researchers zoom in further—to the nerves within each individual sucker, a ring of muscular tissue, which octopuses use to sense and taste their surroundings.

“There is a sucker ganglion, or nerve center, located in the stalk of every sucker. For some species of octopuses, that’s over a thousand ganglia,” says Cassady Olson, a graduate student at the University of Chicago who works with Cliff Ragsdale, a leading expert in octopus neuroscience.

Given that each sucker has its own nerve centers—connected by a long axial nerve cord running down the limb—and each arm has hundreds of suckers, things get complicated very quickly, as researchers have historically struggled to study this peripheral nervous system, as it’s called, within the octopus’s body.

“The large size of the brain makes it both really exciting to study and really challenging,” says Z. Yan Wang, an assistant professor of biology and psychology at the University of Washington. “Many of the tools available for neuroscience have to be adjusted or customized specifically for octopuses and other cephalopods because of their unique body plans.”

While each limb acts independently, signals are transmitted back to the octopus’s central nervous system. The octopus’ brain sits between its eyes at the front of its mantle, or head, couched between its two optic lobes, large bean-shaped neural organs that help octopuses see the world around them. These optic lobes are just two of the over 30 lobes experts study within the animal’s centralized brain, as each lobe helps the octopus process its environment.

This elaborate neural architecture is critical given the octopus’s dual role in the ecosystem as both predator and prey. Without natural defenses like a hard shell, octopuses have evolved a highly adaptable nervous system that allows them to rapidly process information and adjust as needed, helping their chances of survival.

Some similarities remain

While the octopus’s decentralized nervous system makes it a unique evolutionary example, it does have some structures similar to or analogous to the human nervous system.

“The octopus has a central brain mass located between its eyes, and an axial nerve cord running down each arm (similar to a spinal cord),” says Wang. “The octopus has many sensory systems that we are familiar with, such as vision, touch (somatosensation), chemosensation, and gravity sensing.”

Neuroscientists have homed in on these similarities to understand how these structures may have evolved across the different branches in the tree of life. As the most recent common ancestor for humans and octopuses lived around 750 million years ago, experts believe that many similarities, from similar camera-like eyes to maps of neural activities, evolved separately in a process known as convergent evolution.

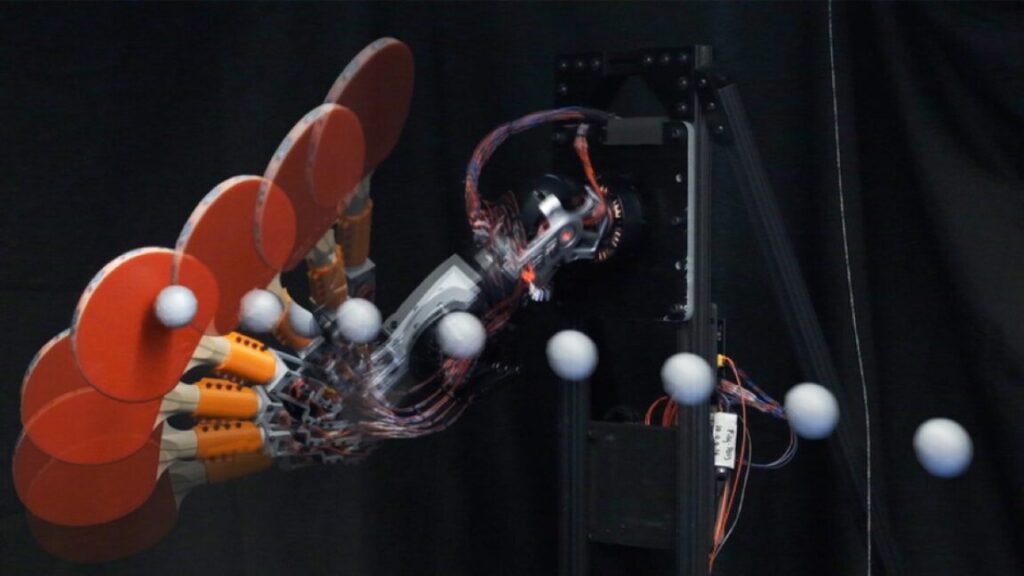

While these similarities shed light on evolution’s independent paths, they also offer valuable insights for fields like soft robotics and regenerative medicine.

Occasionally, unique individuals—like an octopus with an unexpected number of limbs—can provide even deeper clues into how this remarkable nervous system functions and adapts.

Nine arms, no problem

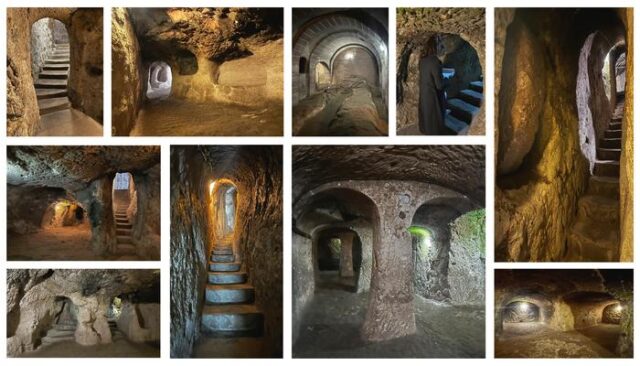

In 2021, researchers from the Institute of Marine Research in Spain used an underwater camera to follow a male Octopus vulgaris, or common octopus. On its left side, three arms were intact, while the others were reduced to uneven, stumpy lengths, sharply bitten off at varying points. Although the researchers didn’t witness the injury itself, they observed that the front right arm—known as R1—was regenerating unusually, splitting into two separate limbs and giving the octopus a total of nine arms.

“In this individual, we believe this condition was a result of abnormal regeneration [a genetic mutation] after an encounter with a predator,” explains Sam Soule, one of the researchers and the first author on the corresponding paper recently published in Animals.

The researchers named the octopus Salvador due to its bifurcated arm coiling up on itself like the two upturned ends of Salvador Dali’s moustache. For two years, the team studied the cephalopod’s behavior and found that it used its bifurcated arm less when doing “riskier” movements such as exploring or grabbing food, which would force the animal to stretch its arm out and expose it to further injury.

“One of the conclusions of our research is that the octopus likely retains a long-term memory of the original injury, as it tends to use the bifurcated arms for less risky tasks compared to the others,” elaborates Jorge Hernández Urcera, a lead author of the study. “This idea of lasting memory brought to mind Dalí’s famous painting The Persistence of Memory, which ultimately became the title of the paper we published on monitoring this particular octopus.”

While the octopus acted more protective of its extra limb, its nervous system had adapted to using the extra appendage, as the octopus was observed, after some time recovering from its injuries, using its ninth arm for probing its environment.

“That nine-armed octopus is a perfect example of just how adaptable these animals are,” Pelled adds. “Most animals would struggle with an unusual body part, but not the octopus. In this case, the octopus had a bifurcated (split) arm and still used it effectively, just like any other arm. That tells us the nervous system didn’t treat it as a mistake—it figured out how to make it work.”

Kenna Hughes-Castleberry is the science communicator at JILA (a joint physics research institute between the National Institute of Standards and Technology and the University of Colorado Boulder) and a freelance science journalist. Her main writing focuses are quantum physics, quantum technology, deep technology, social media, and the diversity of people in these fields, particularly women and people from minority ethnic and racial groups. Follow her on LinkedIn or visit her website.

The nine-armed octopus and the oddities of the cephalopod nervous system Read More »