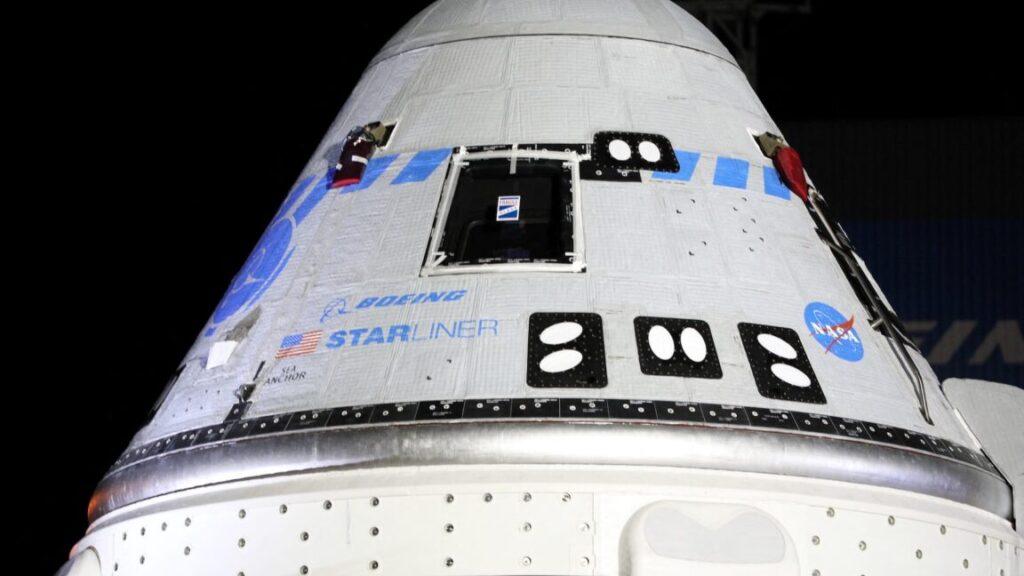

NASA chief classifies Starliner flight as “Type A” mishap, says agency made mistakes

Still, after astronauts Butch Wilmore and Suni Williams eventually docked at the station, Boeing officials declared success. “We accomplished a lot, and really more than expected,” said Mark Nappi, vice president and manager of Boeing’s Commercial Crew Program, during a post-docking news conference. “We just had an outstanding day.”

Over the subsequent weeks of the summer of 2024, NASA mostly backed Boeing, saying that its primary option was bringing the crew home on Starliner.

Finally, by early August, NASA publicly wavered and admitted that Wilmore and Williams might return on a SpaceX Crew Dragon spacecraft. Yet Boeing remained steadfast. On a Boeing website called “Starliner Updates” that has since gone offline, as late as August 2, 2024, the company was declaring that its “confidence remains high” in Starliner’s return with crew (see archive).

It was, in fact, not outstanding

However, on August 24, NASA made it official and decided that Wilmore and Williams would not fly back on Starliner. Instead, the crew would come home on a Crew Dragon. Wilmore and Williams safely eventually returned to Earth in March 2025 as part of the Crew 9 mission.

The true danger the astronauts faced on board Starliner was not publicly revealed until after they landed and flew back to Houston. In an interview with Ars, Wilmore described the tense minutes when he had to take control of Starliner as its thrusters began to fail, one after the other.

Essentially, Wilmore could not fully control Starliner any longer. But simply abandoning the docking attempt was not a palatable solution. Just as the thrusters were needed to control the vehicle during the docking process, they were also necessary to position Starliner for its deorbit burn and reentry to Earth’s atmosphere. So Wilmore had to contemplate whether it was riskier to approach the space station or try to fly back to Earth.

“I don’t know that we can come back to Earth at that point,” he said. “I don’t know if we can. And matter of fact, I’m thinking we probably can’t. So there we are, loss of 6DOF control, four aft thrusters down, and I’m visualizing orbital mechanics. The space station is nose down. So we’re not exactly level with the station, but below it. If you’re below the station, you’re moving faster. That’s orbital mechanics. It’s going to make you move away from the station. So I’m doing all of this in my mind. I don’t know what control I have. What if I lose another thruster? What if we lose comm? What am I going to do?”

One thing that has surprised outside observers since publication of Wilmore’s harrowing experience is how NASA, knowing all of this, could have seriously entertained bringing the crew home on Starliner.

NASA chief classifies Starliner flight as “Type A” mishap, says agency made mistakes Read More »