Wing Commander III: “Isn’t that the guy from Star Wars?”

C:ArsGames looks at a vanguard of the multimedia FMV future that never quite came to pass.

It’s Christmas of 1994, and I am 16 years old. Sitting on the table in our family room next to a pile of cow-spotted boxes is the most incredible thing in the world: a brand-new Gateway 66MHz Pentium tower, with a 540MB hard disk drive, 8MB of RAM, and, most importantly, a CD-ROM drive. I am agog, practically trembling with barely suppressed joy, my bored Gen-X teenager mask threatening to slip and let actual feelings out. My life was about to change—at least where games were concerned.

I’d been working for several months at Babbage’s store No. 9, near Baybrook Mall in southeast suburban Houston. Although the Gateway PC’s arrival on Christmas morning was utterly unexpected, the choice of what game to buy required no planning at all. I’d already decided a few weeks earlier, when Chris Roberts’ latest opus had been drop-shipped to our shelves, just in time for the holiday season. The choice made itself, really.

Gimli and Luke, together at last! Credit: Origin Systems / Electronic Arts

The moment Babbage’s opened its doors on December 26—a day I had off, fortunately—I was there, checkbook in hand. One entire paycheck’s worth of capitalism later, I was sprinting out to my creaky 280-Z, sweatily clutching two boxes—one an impulse buy, The Star Trek: The Next Generation Interactive Technical Manual, and the other a game I felt sure would be the best thing I’d ever played or ever would play: Origin’s Wing Commander III: The Heart of the Tiger. On the backs of Wing Commander I and Wing Commander II, how could it not be?!

The movie is on my computer!

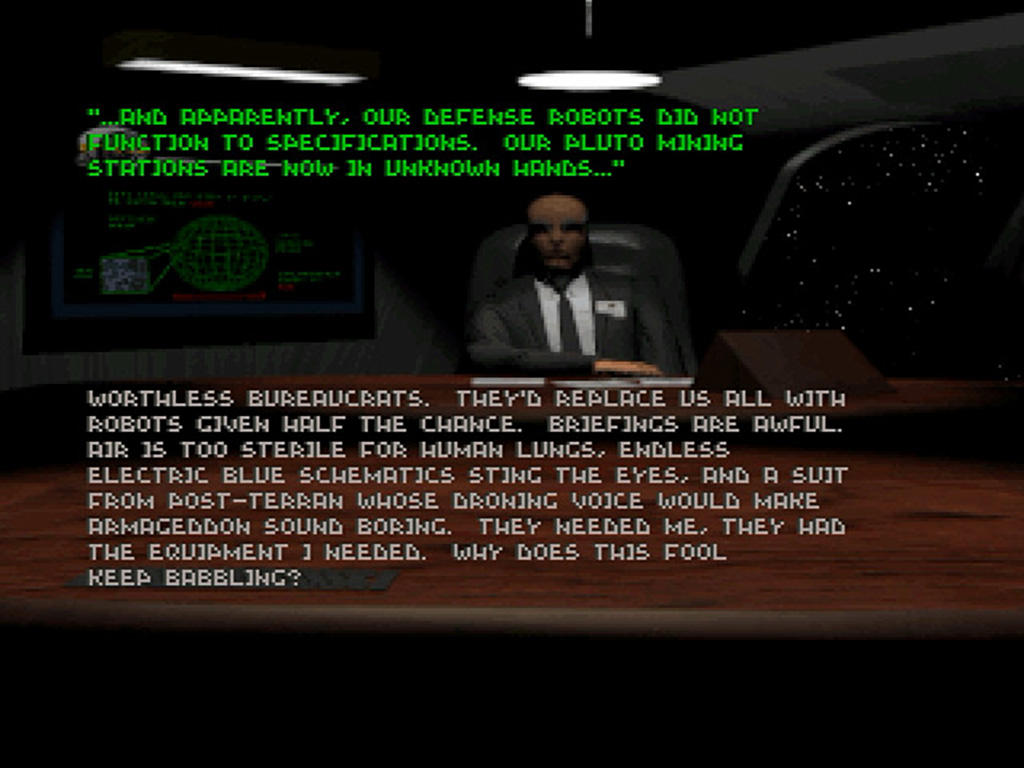

It’s easy to pooh-pooh full-motion video games here in 2026; from our vantage point, we know the much-anticipated “Siliwood” revolution that was supposed to transform entertainment and usher interactivity into all media by the end of the millennium utterly failed to materialize, leaving in its wake a series of often spectacularly expensive titles filled with grainy interlaced video and ersatz gameplay. Even the standout titles—smash hits like Roberta Williams’ Phantasmagoria or Cyan’s Riven—were, on the whole, kinda mediocre.

But we hadn’t learned any of those lessons yet in 1994, and Wing Commander III went hard. The game’s production was absurdly expensive, with a budget that eventually reached an unheard-of $4 million. The shooting script runs to 324 printed pages (a typical feature film script is less than half that long—Coppola’s working script for The Godfather was 136 pages). Even the game itself was enormous—in an era where a single CD-ROM was already considered ludicrously large, WC3 sprawled ostentatiously across four of the 600MB-or-so discs.

Still got these damn things in my closet after all these years. Credit: Lee Hutchinson

Why so big? Because this was the future, and the future—or so we thought at the time—belonged to full-motion video.

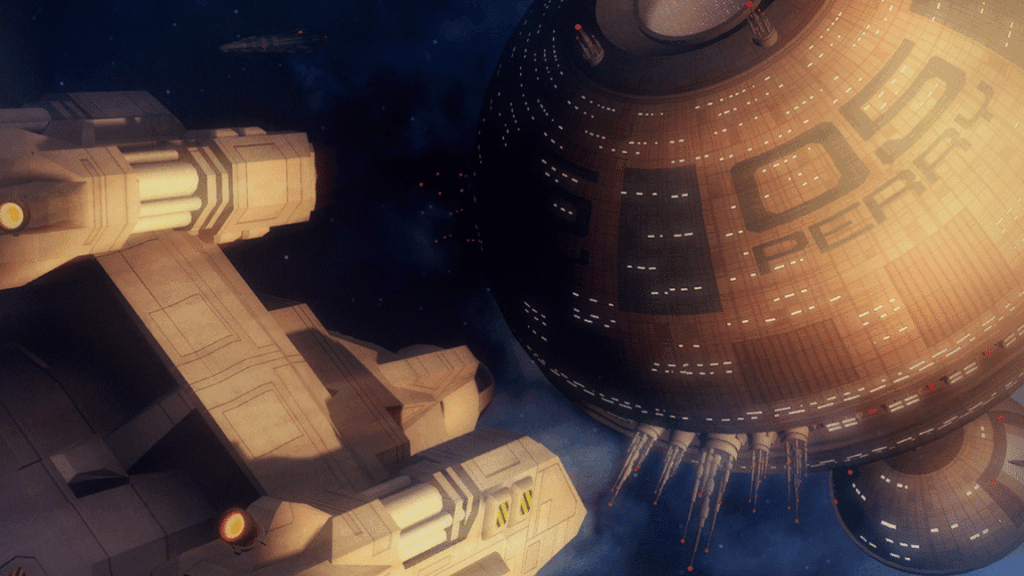

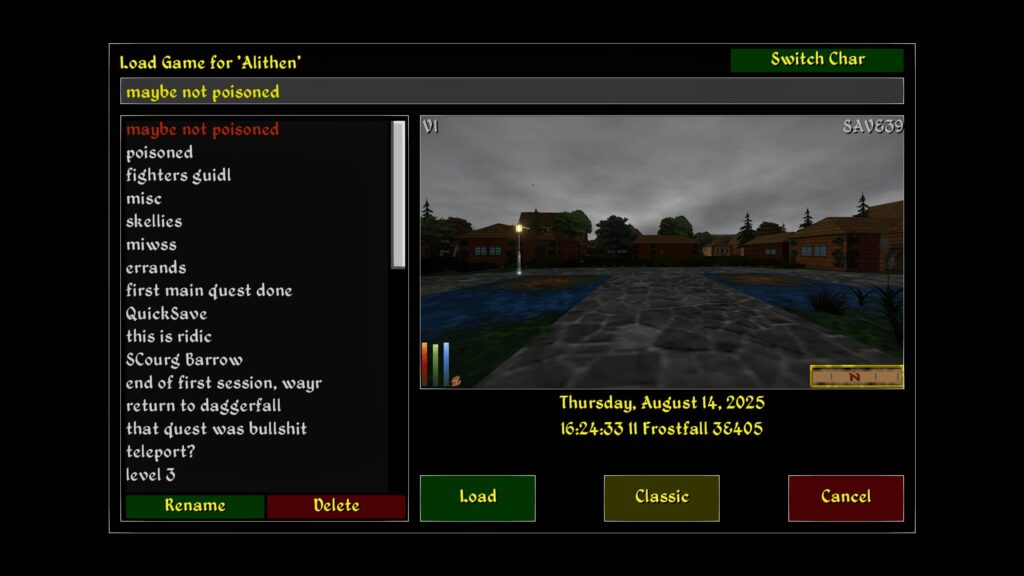

The Wing Commander III opening cinematic in all its pixelated glory.

That’s Wing Commander III’s epic opening cinematic, upscaled for YouTube. Even without the upscaling and watching it on a 15-inch CRT, I was entranced. I was blown away. Before the credits were done rolling, I was already on the phone with my buddies Steve and Matt, telling them to stop what they were doing and get over here immediately to see this thing—it’s like a whole movie! A movie, on the computer! Surely only Chris Roberts could conceive and execute such audacity!

And what a movie it was, with an actual-for-real Hollywood cast. Malcolm McDowell! John Rhys-Davies! Jason Bernard! Tom Wilson! Ginger Lynn Allen, whom 16-year-old me definitely did not want his parents to know that I recognized! And, of course, the biggest face on the box: Luke Skywalker himself, Mark Hamill, representing you. You, the decorated hero of the Vega campaign, the formerly disgraced “Coward of K’Tithrak Mang,” the recently redeemed savior of humanity, now sporting an actual name: Colonel Christopher Blair. (“Blair” is an evolution of the internal codename used by Origin to refer to the main character in the previous two Wing Commander titles—”Bluehair.”)

I’d watch Malcolm McDowell in anything. Malcolm McDowell is my cinematic love language. Credit: Origin Systems / Electronic Arts

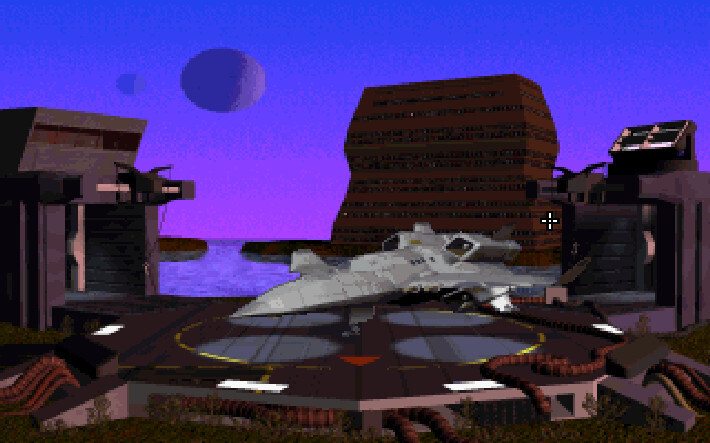

Once the jaw-dropping intro finishes, the player finds Colonel Blair as the newly invested squadron commander aboard the aging carrier TCS Victory, wandering the corridors and having FMV conversations with a few other members of the carrier’s crew. From there, it’s a short hop to the first mission—because beneath all the FMV glitz, Origin still had to provide an actual, you know, game for folks to play.

Through a rose-tinted helmet visor

The game itself is…fine. It’s fine. The polygonal graphics are a welcome step up from the previous two Wing Commander titles’ bitmapped sprites, and the missions themselves manage to avoid many of the “space is gigantic and things take forever to happen” design missteps that plagued LucasArts’ X-Wing (but not, fortunately, TIE Fighter). You fly from point to point and shoot bad guys until they’re dead. Sometimes there are escort missions, sometimes you’re hitting capital ships, and there’s even a (very clunky) planetary bombing mission at the very end that feels like it directly apes the Death Star trench run while doing everything it can to shout “NO THIS IS NOT STAR WARS THIS IS VERY DIFFERENT!”

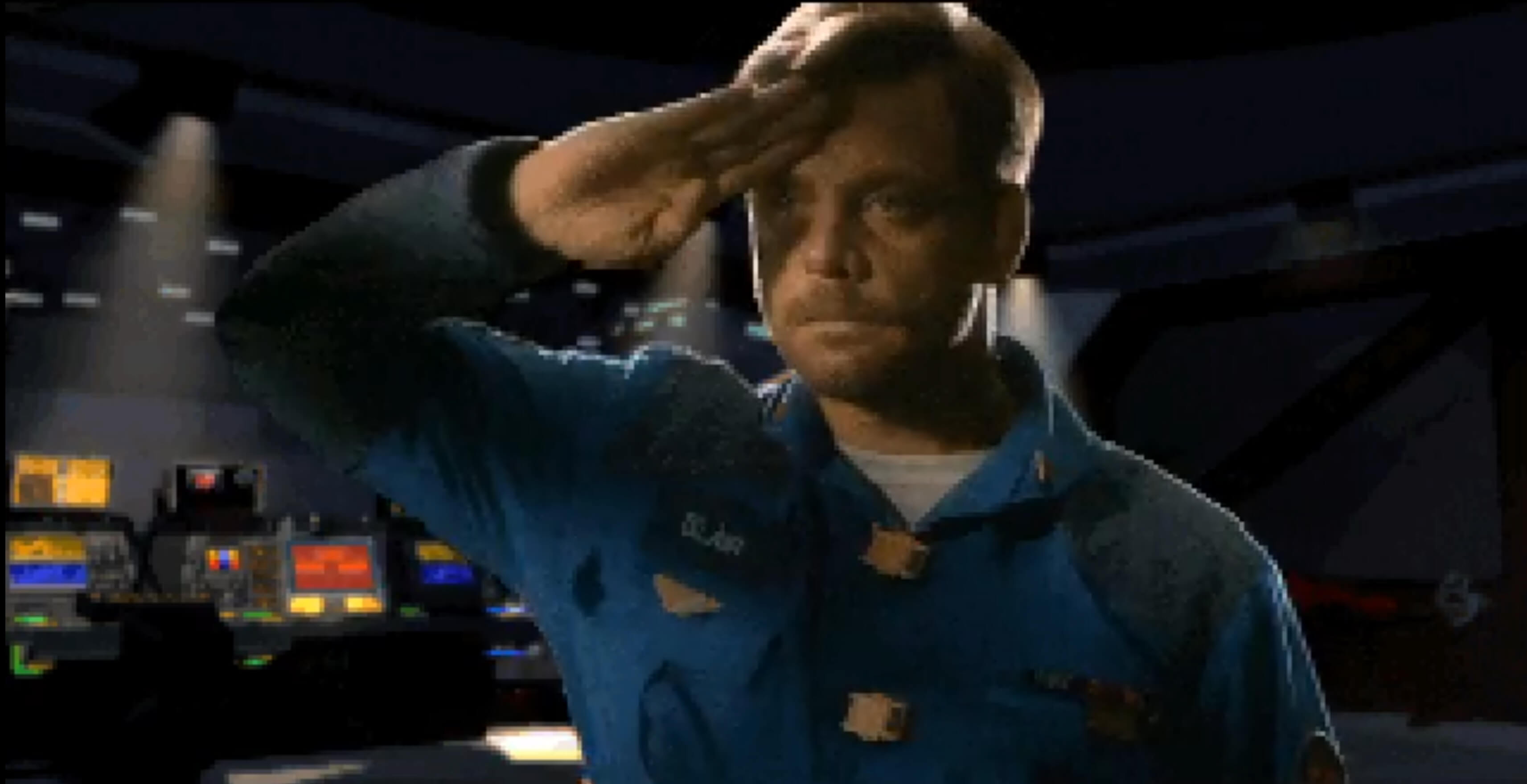

That salute is… definitely a choice. Credit: Origin Systems / Electronic Arts

The space combat is serviceable, but the game also very clearly knows why we’re here: to watch a dead-eyed Mark Hamill with five days of beard stubble fulfill our “I am flying a spaceship” hero fantasies while trading banter with Tom Wilson’s Maniac (“How many people here know about the Maniac? …what, nobody?!”) and receiving fatherly advice from Jason Bernard’s Captain Eisen. And maybe, just maybe, we’d also save the universe and get the girl—either Ginger Lynn’s chief technician Rachel Coriolis or fellow pilot “Flint” Peters, played by Jennifer MacDonald.

(Perhaps unsurprisingly, given the primary purchasing demographic, players tended to overwhelmingly choose Rachel—though this might also have something to do with the fact that if you don’t choose Rachel, you can’t customize your missile loadout for some important missions near the end of the game).

Who doesn’t enjoy a good old-fashioned space love triangle? Credit: Origin Systems / Electronic Arts

Worth a revisit? Definitely!

I will let others more qualified than me opine on whether or not Wing Commander III succeeded at the game-y things it set out to do—folks looking to read an educated opinion should consult Jimmy Maher’s thoughts on the matter over at his site, The Digital Antiquarian.

But regardless of whether or not it was a good game in its time, and regardless of whether or not it’s an effective space combat sim, it is absolutely undeniable that it’s a fascinating historical curiosity—one well worth dropping three bucks on at the GOG store (it’s on sale!).

There are cheats built into the game to help you skip past the actual space missions, which range in difficulty from “cream puff” to “obviously untested and totally broken” because just like in 1994, what we’re really here for is the beautiful failed experiment in interactive entertainment that is the movie portion of the game, especially when Malcolm McDowell shows up as Admiral Tolwyn and, in typical Malcom McDowell fashion, totally commits to the role far beyond what would have been required to pull it off and turns in his scenery-chewing best. (He’s even better in Wing Commander IV, though we’ll save that for another day.)

You could find a worse way today to spend those three bucks. Slap on that flight suit, colonel—the galaxy isn’t going to save itself!

Wing Commander III: “Isn’t that the guy from Star Wars?” Read More »