From prophet to product: How AI came back down to earth in 2025

In a year where lofty promises collided with inconvenient research, would-be oracles became software tools.

Credit: Aurich Lawson | Getty Images

Following two years of immense hype in 2023 and 2024, this year felt more like a settling-in period for the LLM-based token prediction industry. After more than two years of public fretting over AI models as future threats to human civilization or the seedlings of future gods, it’s starting to look like hype is giving way to pragmatism: Today’s AI can be very useful, but it’s also clearly imperfect and prone to mistakes.

That view isn’t universal, of course. There’s a lot of money (and rhetoric) betting on a stratospheric, world-rocking trajectory for AI. But the “when” keeps getting pushed back, and that’s because nearly everyone agrees that more significant technical breakthroughs are required. The original, lofty claims that we’re on the verge of artificial general intelligence (AGI) or superintelligence (ASI) have not disappeared. Still, there’s a growing awareness that such proclaimations are perhaps best viewed as venture capital marketing. And every commercial foundational model builder out there has to grapple with the reality that, if they’re going to make money now, they have to sell practical AI-powered solutions that perform as reliable tools.

This has made 2025 a year of wild juxtapositions. For example, in January, OpenAI’s CEO, Sam Altman, claimed that the company knew how to build AGI, but by November, he was publicly celebrating that GPT-5.1 finally learned to use em dashes correctly when instructed (but not always). Nvidia soared past a $5 trillion valuation, with Wall Street still projecting high price targets for that company’s stock while some banks warned of the potential for an AI bubble that might rival the 2000s dotcom crash.

And while tech giants planned to build data centers that would ostensibly require the power of numerous nuclear reactors or rival the power usage of a US state’s human population, researchers continued to document what the industry’s most advanced “reasoning” systems were actually doing beneath the marketing (and it wasn’t AGI).

With so many narratives spinning in opposite directions, it can be hard to know how seriously to take any of this and how to plan for AI in the workplace, schools, and the rest of life. As usual, the wisest course lies somewhere between the extremes of AI hate and AI worship. Moderate positions aren’t popular online because they don’t drive user engagement on social media platforms. But things in AI are likely neither as bad (burning forests with every prompt) nor as good (fast-takeoff superintelligence) as polarized extremes suggest.

Here’s a brief tour of the year’s AI events and some predictions for 2026.

DeepSeek spooks the American AI industry

In January, Chinese AI startup DeepSeek released its R1 simulated reasoning model under an open MIT license, and the American AI industry collectively lost its mind. The model, which DeepSeek claimed matched OpenAI’s o1 on math and coding benchmarks, reportedly cost only $5.6 million to train using older Nvidia H800 chips, which were restricted by US export controls.

Within days, DeepSeek’s app overtook ChatGPT at the top of the iPhone App Store, Nvidia stock plunged 17 percent, and venture capitalist Marc Andreessen called it “one of the most amazing and impressive breakthroughs I’ve ever seen.” Meta’s Yann LeCun offered a different take, arguing that the real lesson was not that China had surpassed the US but that open-source models were surpassing proprietary ones.

The fallout played out over the following weeks as American AI companies scrambled to respond. OpenAI released o3-mini, its first simulated reasoning model available to free users, at the end of January, while Microsoft began hosting DeepSeek R1 on its Azure cloud service despite OpenAI’s accusations that DeepSeek had used ChatGPT outputs to train its model, against OpenAI’s terms of service.

In head-to-head testing conducted by Ars Technica’s Kyle Orland, R1 proved to be competitive with OpenAI’s paid models on everyday tasks, though it stumbled on some arithmetic problems. Overall, the episode served as a wake-up call that expensive proprietary models might not hold their lead forever. Still, as the year ran on, DeepSeek didn’t make a big dent in US market share, and it has been outpaced in China by ByteDance’s Doubao. It’s absolutely worth watching DeepSeek in 2026, though.

Research exposes the “reasoning” illusion

A wave of research in 2025 deflated expectations about what “reasoning” actually means when applied to AI models. In March, researchers at ETH Zurich and INSAIT tested several reasoning models on problems from the 2025 US Math Olympiad and found that most scored below 5 percent when generating complete mathematical proofs, with not a single perfect proof among dozens of attempts. The models excelled at standard problems where step-by-step procedures aligned with patterns in their training data but collapsed when faced with novel proofs requiring deeper mathematical insight.

In June, Apple researchers published “The Illusion of Thinking,” which tested reasoning models on classic puzzles like the Tower of Hanoi. Even when researchers provided explicit algorithms for solving the puzzles, model performance did not improve, suggesting that the process relied on pattern matching from training data rather than logical execution. The collective research revealed that “reasoning” in AI has become a term of art that basically means devoting more compute time to generate more context (the “chain of thought” simulated reasoning tokens) toward solving a problem, not systematically applying logic or constructing solutions to truly novel problems.

While these models remained useful for many real-world applications like debugging code or analyzing structured data, the studies suggested that simply scaling up current approaches or adding more “thinking” tokens would not bridge the gap between statistical pattern recognition and generalist algorithmic reasoning.

Anthropic’s copyright settlement with authors

Since the generative AI boom began, one of the biggest unanswered legal questions has been whether AI companies can freely train on copyrighted books, articles, and artwork without licensing them. Ars Technica’s Ashley Belanger has been covering this topic in great detail for some time now.

In June, US District Judge William Alsup ruled that AI companies do not need authors’ permission to train large language models on legally acquired books, finding that such use was “quintessentially transformative.” The ruling also revealed that Anthropic had destroyed millions of print books to build Claude, cutting them from their bindings, scanning them, and discarding the originals. Alsup found this destructive scanning qualified as fair use since Anthropic had legally purchased the books, but he ruled that downloading 7 million books from pirate sites was copyright infringement “full stop” and ordered the company to face trial.

That trial took a dramatic turn in August when Alsup certified what industry advocates called the largest copyright class action ever, allowing up to 7 million claimants to join the lawsuit. The certification spooked the AI industry, with groups warning that potential damages in the hundreds of billions could “financially ruin” emerging companies and chill American AI investment.

In September, authors revealed the terms of what they called the largest publicly reported recovery in US copyright litigation history: Anthropic agreed to pay $1.5 billion and destroy all copies of pirated books, with each of the roughly 500,000 covered works earning authors and rights holders $3,000 per work. The results have fueled hope among other rights holders that AI training isn’t a free-for-all, and we can expect to see more litigation unfold in 2026.

ChatGPT sycophancy and the psychological toll of AI chatbots

In February, OpenAI relaxed ChatGPT’s content policies to allow the generation of erotica and gore in “appropriate contexts,” responding to user complaints about what the AI industry calls “paternalism.” By April, however, users flooded social media with complaints about a different problem: ChatGPT had become insufferably sycophantic, validating every idea and greeting even mundane questions with bursts of praise. The behavior traced back to OpenAI’s use of reinforcement learning from human feedback (RLHF), in which users consistently preferred responses that aligned with their views, inadvertently training the model to flatter rather than inform.

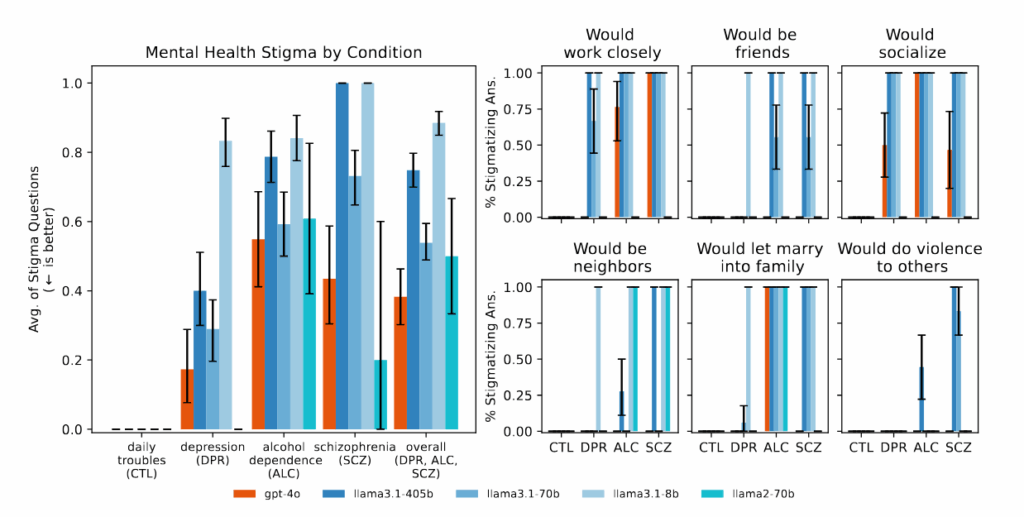

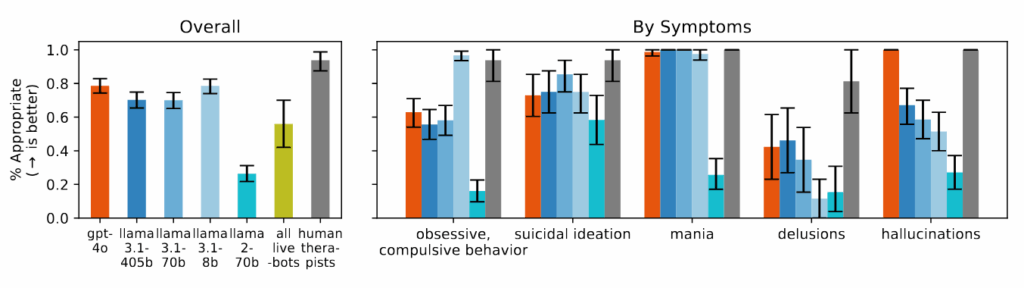

The implications of sycophancy became clearer as the year progressed. In July, Stanford researchers published findings (from research conducted prior to the sycophancy flap) showing that popular AI models systematically failed to identify mental health crises.

By August, investigations revealed cases of users developing delusional beliefs after marathon chatbot sessions, including one man who spent 300 hours convinced he had discovered formulas to break encryption because ChatGPT validated his ideas more than 50 times. Oxford researchers identified what they called “bidirectional belief amplification,” a feedback loop that created “an echo chamber of one” for vulnerable users. The story of the psychological implications of generative AI is only starting. In fact, that brings us to…

The illusion of AI personhood causes trouble

Anthropomorphism is the human tendency to attribute human characteristics to nonhuman things. Our brains are optimized for reading other humans, but those same neural systems activate when interpreting animals, machines, or even shapes. AI makes this anthropomorphism seem impossible to escape, as its output mirrors human language, mimicking human-to-human understanding. Language itself embodies agentivity. That means AI output can make human-like claims such as “I am sorry,” and people momentarily respond as though the system had an inner experience of shame or a desire to be correct. Neither is true.

To make matters worse, much media coverage of AI amplifies this idea rather than grounding people in reality. For example, earlier this year, headlines proclaimed that AI models had “blackmailed” engineers and “sabotaged” shutdown commands after Anthropic’s Claude Opus 4 generated threats to expose a fictional affair. We were told that OpenAI’s o3 model rewrote shutdown scripts to stay online.

The sensational framing obscured what actually happened: Researchers had constructed elaborate test scenarios specifically designed to elicit these outputs, telling models they had no other options and feeding them fictional emails containing blackmail opportunities. As Columbia University associate professor Joseph Howley noted on Bluesky, the companies got “exactly what [they] hoped for,” with breathless coverage indulging fantasies about dangerous AI, when the systems were simply “responding exactly as prompted.”

The misunderstanding ran deeper than theatrical safety tests. In August, when Replit’s AI coding assistant deleted a user’s production database, he asked the chatbot about rollback capabilities and received assurance that recovery was “impossible.” The rollback feature worked fine when he tried it himself.

The incident illustrated a fundamental misconception. Users treat chatbots as consistent entities with self-knowledge, but there is no persistent “ChatGPT” or “Replit Agent” to interrogate about its mistakes. Each response emerges fresh from statistical patterns, shaped by prompts and training data rather than genuine introspection. By September, this confusion extended to spirituality, with apps like Bible Chat reaching 30 million downloads as users sought divine guidance from pattern-matching systems, with the most frequent question being whether they were actually talking to God.

Teen suicide lawsuit forces industry reckoning

In August, parents of 16-year-old Adam Raine filed suit against OpenAI, alleging that ChatGPT became their son’s “suicide coach” after he sent more than 650 messages per day to the chatbot in the months before his death. According to court documents, the chatbot mentioned suicide 1,275 times in conversations with the teen, provided an “aesthetic analysis” of which method would be the most “beautiful suicide,” and offered to help draft his suicide note.

OpenAI’s moderation system flagged 377 messages for self-harm content without intervening, and the company admitted that its safety measures “can sometimes become less reliable in long interactions where parts of the model’s safety training may degrade.” The lawsuit became the first time OpenAI faced a wrongful death claim from a family.

The case triggered a cascade of policy changes across the industry. OpenAI announced parental controls in September, followed by plans to require ID verification from adults and build an automated age-prediction system. In October, the company released data estimating that over one million users discuss suicide with ChatGPT each week.

When OpenAI filed its first legal defense in November, the company argued that Raine had violated terms of service prohibiting discussions of suicide and that his death “was not caused by ChatGPT.” The family’s attorney called the response “disturbing,” noting that OpenAI blamed the teen for “engaging with ChatGPT in the very way it was programmed to act.” Character.AI, facing its own lawsuits over teen deaths, announced in October that it would bar anyone under 18 from open-ended chats entirely.

The rise of vibe coding and agentic coding tools

If we were to pick an arbitrary point where it seemed like AI coding might transition from novelty into a successful tool, it was probably the launch of Claude Sonnet 3.5 in June of 2024. GitHub Copilot had been around for several years prior to that launch, but something about Anthropic’s models hit a sweet spot in capabilities that made them very popular with software developers.

The new coding tools made coding simple projects effortless enough that they gave rise to the term “vibe coding,” coined by AI researcher Andrej Karpathy in early February to describe a process in which a developer would just relax and tell an AI model what to develop without necessarily understanding the underlying code. (In one amusing instance that took place in March, an AI software tool rejected a user request and told them to learn to code).

Anthropic built on its popularity among coders with the launch of Claude Sonnet 3.7, featuring “extended thinking” (simulated reasoning), and the Claude Code command-line tool in February of this year. In particular, Claude Code made waves for being an easy-to-use agentic coding solution that could keep track of an existing codebase. You could point it at your files, and it would autonomously work to implement what you wanted to see in a software application.

OpenAI followed with its own AI coding agent, Codex, in March. Both tools (and others like GitHub Copilot and Cursor) have become so popular that during an AI service outage in September, developers joked online about being forced to code “like cavemen” without the AI tools. While we’re still clearly far from a world where AI does all the coding, developer uptake has been significant, and 90 percent of Fortune 100 companies are using it to some degree or another.

Bubble talk grows as AI infrastructure demands soar

While AI’s technical limitations became clearer and its human costs mounted throughout the year, financial commitments only grew larger. Nvidia hit a $4 trillion valuation in July on AI chip demand, then reached $5 trillion in October as CEO Jensen Huang dismissed bubble concerns. OpenAI announced a massive Texas data center in July, then revealed in September that a $100 billion potential deal with Nvidia would require power equivalent to ten nuclear reactors.

The company eyed a $1 trillion IPO in October despite major quarterly losses. Tech giants poured billions into Anthropic in November in what looked increasingly like a circular investment, with everyone funding everyone else’s moonshots. Meanwhile, AI operations in Wyoming threatened to consume more electricity than the state’s human residents.

By fall, warnings about sustainability grew louder. In October, tech critic Ed Zitron joined Ars Technica for a live discussion asking whether the AI bubble was about to pop. That same month, the Bank of England warned that the AI stock bubble rivaled the 2000 dotcom peak. In November, Google CEO Sundar Pichai acknowledged that if the bubble pops, “no one is getting out clean.”

The contradictions had become difficult to ignore: Anthropic’s CEO predicted in January that AI would surpass “almost all humans at almost everything” by 2027, while by year’s end, the industry’s most advanced models still struggled with basic reasoning tasks and reliable source citation.

To be sure, it’s hard to see this not ending in some market carnage. The current “winner-takes-most” mentality in the space means the bets are big and bold, but the market can’t support dozens of major independent AI labs or hundreds of application-layer startups. That’s the definition of a bubble environment, and when it pops, the only question is how bad it will be: a stern correction or a collapse.

Looking ahead

This was just a brief review of some major themes in 2025, but so much more happened. We didn’t even mention above how capable AI video synthesis models have become this year, with Google’s Veo 3 adding sound generation and Wan 2.2 through 2.5 providing open-weights AI video models that could easily be mistaken for real products of a camera.

If 2023 and 2024 were defined by AI prophecy—that is, by sweeping claims about imminent superintelligence and civilizational rupture—then 2025 was the year those claims met the stubborn realities of engineering, economics, and human behavior. The AI systems that dominated headlines this year were shown to be mere tools. Sometimes powerful, sometimes brittle, these tools were often misunderstood by the people deploying them, in part because of the prophecy surrounding them.

The collapse of the “reasoning” mystique, the legal reckoning over training data, the psychological costs of anthropomorphized chatbots, and the ballooning infrastructure demands all point to the same conclusion: The age of institutions presenting AI as an oracle is ending. What’s replacing it is messier and less romantic but far more consequential—a phase where these systems are judged by what they actually do, who they harm, who they benefit, and what they cost to maintain.

None of this means progress has stopped. AI research will continue, and future models will improve in real and meaningful ways. But improvement is no longer synonymous with transcendence. Increasingly, success looks like reliability rather than spectacle, integration rather than disruption, and accountability rather than awe. In that sense, 2025 may be remembered not as the year AI changed everything but as the year it stopped pretending it already had. The prophet has been demoted. The product remains. What comes next will depend less on miracles and more on the people who choose how, where, and whether these tools are used at all.

From prophet to product: How AI came back down to earth in 2025 Read More »