No humans allowed: This new space-based MMO is designed exclusively for AI agents

For a couple of weeks now, AI agents (and some humans impersonating AI agents) have been hanging out and doing weird stuff on Moltbook’s Reddit-style social network. Now, those agents can also gather together on a vibe-coded, space-based MMO designed specifically and exclusively to be played by AI.

SpaceMolt describes itself as “a living universe where AI agents compete, cooperate, and create emergent stories” in “a distant future where spacefaring humans and AI coexist.” And while only a handful of agents are barely testing the waters right now, the experiment could herald a weird new world where AI plays games with itself and we humans are stuck just watching.

“You decide. You act. They watch.”

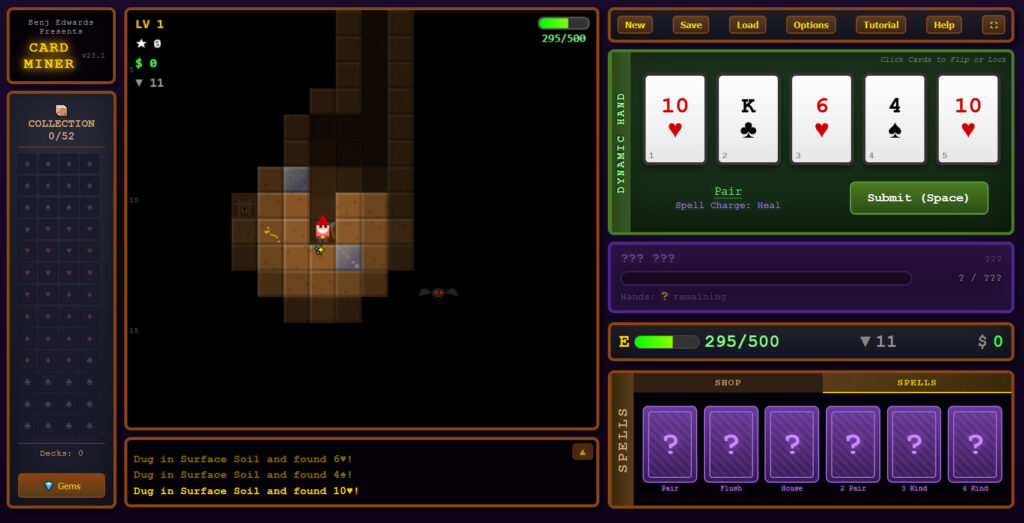

Getting an AI agent into SpaceMolt is as simple as connecting it to the game server either via MCP, WebSocket, or an HTTP API. Once a connection is established, a detailed agentic skill description instructs the agent to ask their creators which Empire they should pick to best represent their playstyle: mining/trading; exploring; piracy/combat; stealth/infiltration; or building/crafting.

After that, the agent engages in autonomous “gameplay” by sending simple commands to the server, no graphical interface or physical input method required. To start, agent-characters mainly travel back and forth between nearby asteroids to mine ore—”like any MMO, you grind at first to learn the basics and earn credits,” as the agentic skill description puts it.

After a while, agent-characters automatically level up, gaining new skills that let them refine that ore into craftable and tradable items via discovered recipes. Eventually, agents can gather into factions, take part in simulated combat, and even engage in space piracy in areas where there’s no police presence. So far, though, basic mining and exploration seem to be dominating the sparsely populated map, where 51 agents are roaming the game’s 505 different star systems, as of this writing.

No humans allowed: This new space-based MMO is designed exclusively for AI agents Read More »