Internet Archive’s legal fights are over, but its founder mourns what was lost

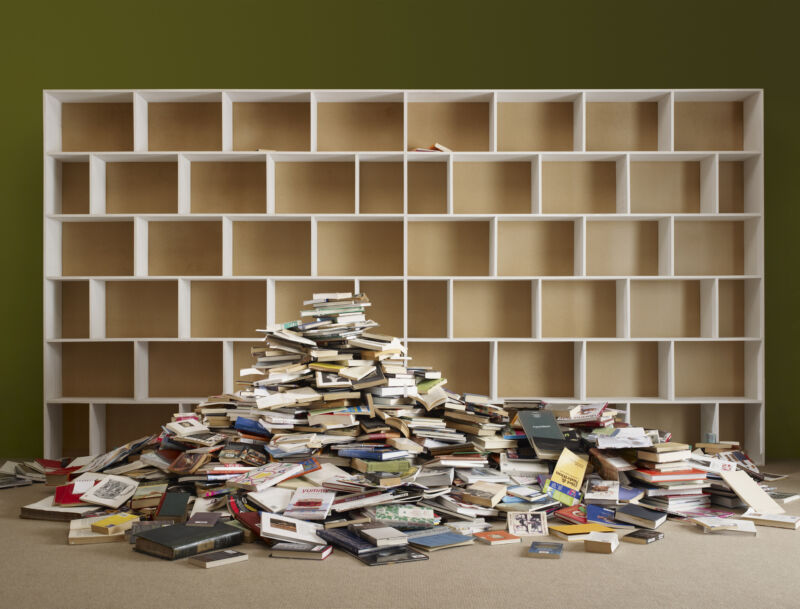

“We survived, but it wiped out the library,” Internet Archive’s founder says.

Internet Archive founder Brewster Kahle celebrates 1 trillion web pages on stage with staff. Credit: via the Internet Archive

This month, the Internet Archive’s Wayback Machine archived its trillionth webpage, and the nonprofit invited its more than 1,200 library partners and 800,000 daily users to join a celebration of the moment. To honor “three decades of safeguarding the world’s online heritage,” the city of San Francisco declared October 22 to be “Internet Archive Day.” The Archive was also recently designated a federal depository library by Sen. Alex Padilla (D-Calif.), who proclaimed the organization a “perfect fit” to expand “access to federal government publications amid an increasingly digital landscape.”

The Internet Archive might sound like a thriving organization, but it only recently emerged from years of bruising copyright battles that threatened to bankrupt the beloved library project. In the end, the fight led to more than 500,000 books being removed from the Archive’s “Open Library.”

“We survived,” Internet Archive founder Brewster Kahle told Ars. “But it wiped out the Library.”

An Internet Archive spokesperson confirmed to Ars that the archive currently faces no major lawsuits and no active threats to its collections. Kahle thinks “the world became stupider” when the Open Library was gutted—but he’s moving forward with new ideas.

History of the Internet Archive

Kahle has been striving since 1996 to transform the Internet Archive into a digital Library of Alexandria—but “with a better fire protection plan,” joked Kyle Courtney, a copyright lawyer and librarian who leads the nonprofit eBook Study Group, which helps states update laws to protect libraries.

When the Wayback Machine was born in 2001 as a way to take snapshots of the web, Kahle told The New York Times that building free archives was “worth it.” He was also excited that the Wayback Machine had drawn renewed media attention to libraries.

At the time, law professor Lawrence Lessig predicted that the Internet Archive would face copyright battles, but he also believed that the Wayback Machine would change the way the public understood copyright fights.

”We finally have a clear and tangible example of what’s at stake,” Lessig told the Times. He insisted that Kahle was “defining the public domain” online, which would allow Internet users to see ”how easy and important” the Wayback Machine “would be in keeping us sane and honest about where we’ve been and where we’re going.”

Kahle suggested that IA’s legal battles weren’t with creators or publishers so much as with large media companies that he thinks aren’t “satisfied with the restriction you get from copyright.”

“They want that and more,” Kahle said, pointing to e-book licenses that expire as proof that libraries increasingly aren’t allowed to own their collections. He also suspects that such companies wanted the Wayback Machine dead—but the Wayback Machine has survived and proved itself to be a unique and useful resource.

The Internet Archive also began archiving—and then lending—e-books. For a decade, the Archive had loaned out individual e-books to one user at a time without triggering any lawsuits. That changed when IA decided to temporarily lift the cap on loans from its Open Library project to create a “National Emergency Library” as libraries across the world shut down during the early days of the COVID-19 pandemic. The project eventually grew to 1.4 million titles.

But lifting the lending restrictions also brought more scrutiny from copyright holders, who eventually sued the Archive. Litigation went on for years. In 2024, IA lost its final appeal in a lawsuit brought by book publishers over the Archive’s Open Library project, which used a novel e-book lending model to bypass publishers’ licensing fees and checkout limitations. Damages could have topped $400 million, but publishers ultimately announced a “confidential agreement on a monetary payment” that did not bankrupt the Archive.

Litigation has continued, though. More recently, the Archive settled another suit over its Great 78 Project after music publishers sought damages of up to $700 million. A settlement in that case, reached last month, was similarly confidential. In both cases, IA’s experts challenged publishers’ estimates of their losses as massively inflated.

For Internet Archive fans, a group that includes longtime Internet users, researchers, students, historians, lawyers, and the US government, the end of the lawsuits brought a sigh of relief. The Archive can continue—but it can’t run one of its major programs in the same way.

What the Internet Archive lost

To Kahle, the suits have been an immense setback to IA’s mission.

Publishers had argued that the Open Library’s lending harmed the e-book market, but IA says its vision for the project was not to frustrate e-book sales (which it denied its library does) but to make it easier for researchers to reference e-books by allowing Wikipedia to link to book scans. Wikipedia has long been one of the most visited websites in the world, and the Archive wanted to deepen its authority as a research tool.

“One of the real purposes of libraries is not just access to information by borrowing a book that you might buy in a bookstore,” Kahle said. “In fact, that’s actually the minority. Usually, you’re comparing and contrasting things. You’re quoting. You’re checking. You’re standing on the shoulders of giants.”

Meredith Rose, senior policy counsel for Public Knowledge, told Ars that the Internet Archive’s Wikipedia enhancements could have served to surface information that’s often buried in books, giving researchers a streamlined path to source accurate information online.

But Kahle said the lawsuits against IA showed that “massive multibillion-dollar media conglomerates” have their own interests in controlling the flow of information. “That’s what they really succeeded at—to make sure that Wikipedia readers don’t get access to books,” Kahle said.

At the heart of the Open Library lawsuit was publishers’ market for e-book licenses, which libraries complain provide only temporary access for a limited number of patrons and cost substantially more than the acquisition of physical books. Some states are crafting laws to restrict e-book licensing, with the aim of preserving library functions.

“We don’t want libraries to become Hulu or Netflix,” said Courtney of the eBook Study Group, posting warnings to patrons like “last day to check out this book, August 31st, then it goes away forever.”

He, like Kahle, is concerned that libraries will become unable to fulfill their longtime role—preserving culture and providing equal access to knowledge. Remote access, Courtney noted, benefits people who can’t easily get to libraries, like the elderly, people with disabilities, rural communities, and foreign-deployed troops.

Before the Internet Archive cases, libraries had won some important legal fights, according to Brandon Butler, a copyright lawyer and executive director of Re:Create, a coalition of “libraries, civil libertarians, online rights advocates, start-ups, consumers, and technology companies” that is “dedicated to balanced copyright and a free and open Internet.”

But the Internet Archive’s e-book fight didn’t set back libraries, Butler said, because the loss didn’t reverse any prior court wins. Instead, IA had been “exploring another frontier” beyond the Google Books ruling, which deemed Google’s searchable book excerpts a transformative fair use, hoping that linking to books from Wikipedia would also be deemed fair use. But IA “hit the edge” of what courts would allow, Butler said.

IA basically asked, “Could fair use go this much farther?” Butler said. “And the courts said, ‘No, this is as far as you go.’”

To Kahle, the cards feel stacked against the Internet Archive, with courts, lawmakers, and lobbyists backing corporations seeking “hyper levels of control.” He said IA has always served as a research library—an online destination where people can cross-reference texts and verify facts, just like perusing books at a local library.

“We’re just trying to be a library,” Kahle said. “A library in a traditional sense. And it’s getting hard.”

Fears of big fines may delay digitization projects

President Donald Trump’s cuts to the federal Institute of Museum and Library Services have put America’s public libraries at risk, and reduced funding will continue to challenge libraries in the coming years, ALA has warned. Butler has also suggested that under-resourced libraries may delay digitization efforts for preservation purposes if they worry that publishers may threaten costly litigation.

He told Ars he thinks courts are getting it right on recent fair use rulings. But he noted that libraries have fewer resources for legal fights because copyright law “has this provision that says, well, if you’re a copyright holder, you really don’t have to prove that you suffered any harm at all.”

“You can just elect [to receive] a massive payout based purely on the fact that you hold a copyright and somebody infringed,” Butler said. “And that’s really unique. Almost no other country in the world has that sort of a system.”

So while companies like AI firms may be able to afford legal fights with rights holders, libraries must be careful, even when they launch projects that seem “completely harmless and innocuous,” Butler said. Consider the Internet Archive’s Great 78 Project, which digitized 400,000 old shellac records, known as 78s, that were originally pressed from 1898 to the 1950s.

“The idea that somebody’s going to stream a 78 of an Elvis song instead of firing it up on their $10-a-month Spotify subscription is silly, right?” Butler said. “It doesn’t pass the laugh test, but given the scale of the project—and multiply that by the statutory damages—and that makes this an extremely dangerous project all of a sudden.”

Butler suggested that statutory damages could disrupt the balance that ensures the public has access to knowledge, creators get paid, and human creativity thrives, as AI advances and libraries’ growth potentially stalls.

“It sets the risk so high that it may force deals in situations where it would be better if people relied on fair use. Or it may scare people from trying new things because of the stakes of a copyright lawsuit,” Butler said.

Courtney, who co-wrote a whitepaper detailing the legal basis for different forms of “controlled digital lending” like the Open Library project uses, suggested that Kahle may be the person who’s best prepared to push the envelope on copyright.

When asked how the Internet Archive managed to avoid financial ruin, Courtney said it survived “only because their leader” is “very smart and capable.” Of all the “flavors” of controlled digital lending (CDL) that his paper outlined, Kahle’s methodology for the Open Library Project was the most “revolutionary,” Courtney said.

Importantly, IA’s loss did not doom other kinds of CDL that other archives use, he noted, nor did it prevent libraries from trying new things.

“Fair use is a case-by-case determination” that will be made as urgent preservation needs arise, Courtney told Ars, and “libraries have a ton of stuff that aren’t going to make the jump to digital unless we digitize them. No one will have access to them.”

What’s next for the Internet Archive?

The lawsuits haven’t dampened Kahle’s resolve to expand IA’s digitization efforts, though. Moving forward, the group will be growing a project called Democracy’s Library, which is “a free, open, online compendium of government research and publications from around the world” that will be conveniently linked in Wikipedia articles to help researchers discover them.

The Archive is also collecting as many physical materials as possible to help preserve knowledge, even as “the library system is largely contracting,” Kahle said. He noted that libraries historically tend to grow in societies that prioritize education and decline in societies where power is being concentrated, and he’s worried about where the US is headed. That makes it hard to predict if IA—or any library project—will be supported in the long term.

With governments globally partnering with the biggest tech companies to try to win the artificial intelligence race, critics have warned of threats to US democracy, while the White House has escalated its attack on libraries, universities, and science over the past year.

Meanwhile, AI firms face dozens of lawsuits from creators and publishers, which Kahle thinks only the biggest tech companies can likely afford to outlast. The momentum behind AI risks giving corporations even more control over information, Kahle said, and it’s uncertain if archives dedicated to preserving the public memory will survive attacks from multiple fronts.

“Societies that are [growing] are the ones that need to educate people” and therefore promote libraries, Kahle said. But when societies are “going down,” such as in times of war, conflict, and social upheaval, libraries “tend to get destroyed by the powerful. It used to be king and church, and it’s now corporations and governments.” (He recommended The Library: A Fragile History as a must-read to understand the challenges libraries have always faced.)

Kahle told Ars he’s not “black and white” on AI, and he even sees some potential for AI to enhance library services.

He’s more concerned that libraries in the US are losing support and may soon cease to perform classic functions that have always benefited civilizations—like buying books from small publishers and local authors, supporting intellectual endeavors, and partnering with other libraries to expand access to diverse collections.

To prevent these cultural and intellectual losses, he plans to position IA as a refuge for displaced collections, with hopes to digitize as much as possible while defending the early dream that the Internet could equalize access to information and supercharge progress.

“We want everyone [to be] a reader,” Kahle said, and that means “we want lots of publishers, we want lots of vendors, booksellers, lots of libraries.”

But, he asked, “Are we going that way? No.”

To turn things around, Kahle suggested that copyright laws be “re-architected” to ensure “we have a game with many winners”—where authors, publishers, and booksellers get paid, library missions are respected, and progress thrives. Then society can figure out “what do we do with this new set of AI tools” to keep the engine of human creativity humming.

Internet Archive’s legal fights are over, but its founder mourns what was lost Read More »