Senators count the shady ways data centers pass energy costs on to Americans

Senators demand Big Tech pay upfront for data center spikes in electricity bills.

Senators launched a probe Tuesday demanding that tech companies explain exactly how they plan to prevent data center projects from increasing electricity bills in communities where prices are already skyrocketing.

In letters to seven AI firms, Senators Elizabeth Warren (D-Mass.), Chris Van Hollen (D-Md.), and Richard Blumenthal (D-Conn.) cited a study estimating that “electricity prices have increased by as much as 267 percent in the past five years” in “areas located near significant data center activity.”

Prices increase, senators noted, when utility companies build out extra infrastructure to meet data centers’ energy demands—which can amount to one customer suddenly consuming as much power as an entire city. They also increase when demand for local power outweighs supply. In some cases, residents are blindsided by higher bills, not even realizing a data center project was approved, because tech companies seem intent on dodging backlash and frequently do not allow terms of deals to be publicly disclosed.

AI firms “ask public officials to sign non-disclosure agreements (NDAs) preventing them from sharing information with their constituents, operate through what appear to be shell companies to mask the real owner of the data center, and require that landowners sign NDAs as part of the land sale while telling them only that a ‘Fortune 100 company’ is planning an ‘industrial development’ seemingly in an attempt to hide the very existence of the data center,” senators wrote.

States like Virginia with the highest concentration of data centers could see average electricity prices increase by another 25 percent by 2030, senators noted. But price increases aren’t limited to the states allegedly striking shady deals with tech companies and greenlighting data center projects, they said. “Interconnected and interstate power grids can lead to a data center built in one state raising costs for residents of a neighboring state,” senators reported.

Under fire for supposedly only pretending to care about keeping neighbors’ costs low were Amazon, Google, Meta, Microsoft, Equinix, Digital Realty, and CoreWeave. Senators accused firms of paying “lip service,” claiming that they would do everything in their power to avoid increasing residential electricity costs, while actively lobbying to pass billions in costs on to their neighbors.

For example, Amazon publicly claimed it would “make sure” it would cover costs so they wouldn’t be passed on. But it’s also a member of an industry lobbying group, the Data Center Coalition, that “has opposed state regulatory decisions requiring data center companies to pay a higher percentage of costs upfront,” senators wrote. And Google made similar statements, despite having an executive who opposed a regulatory solution that would set data centers into their own “rate class”—and therefore responsible for grid improvement costs that could not be passed on to other customers—on the grounds that it was supposedly “discriminatory.”

“The current, socialized model of electricity ratepaying,” senators explained—where costs are shared across all users—”was not designed for an era where just one customer requires the same amount of electricity as some of the largest cities in America.”

Particularly problematic, senators emphasized, were reports that tech firms were getting discounts on energy costs as utility companies competed for their business, while prices went up for their neighbors.

Ars contacted all firms targeted by lawmakers. Four did not respond. Microsoft and Meta declined to comment. Digital Realty told Ars that it “looks forward to working with all elected officials to continue to invest in the digital infrastructure required to support America’s leadership in technology, which underpins modern life and creates high-paying jobs.”

Regulatory pressure likely to increase as bills go up

Senators are likely exploring whether to pass legislation that would help combat price increases that they say cause average Americans to struggle to keep the lights on. They’ve asked tech companies to respond to their biggest questions about data center projects by January 12, 2026.

Among their top questions, senators wanted to know about firms’ internal projections looking forward with data center projects. That includes sharing their projected energy use through 2030, as well as the “impact of your AI data centers on regional utility costs.” Companies are also expected to explain how “internal projections of data center energy consumption” justify any “opposition to the creation of a distinct data center rate class.”

Additionally, senators asked firms to outline steps they’ve taken to prevent passing on costs to neighbors and details of any impact studies companies have conducted.

Likely to raise the most eyebrows, however, would be answers to questions about “tax deductions or other financial incentives” tech firms have received from city and state governments. Those numbers would be interesting to compare with other information senators demanded that companies share, detailing how much they’ve spent on lobbying and advocacy for data centers. Senators appear keen to know how much tech companies are paying to avoid covering a proportionate amount of infrastructure costs.

“To protect consumers, data centers must pay a greater share of the costs upfront for future energy usage and updates to the electrical grid provided specifically to accommodate data centers’ energy needs,” senators wrote.

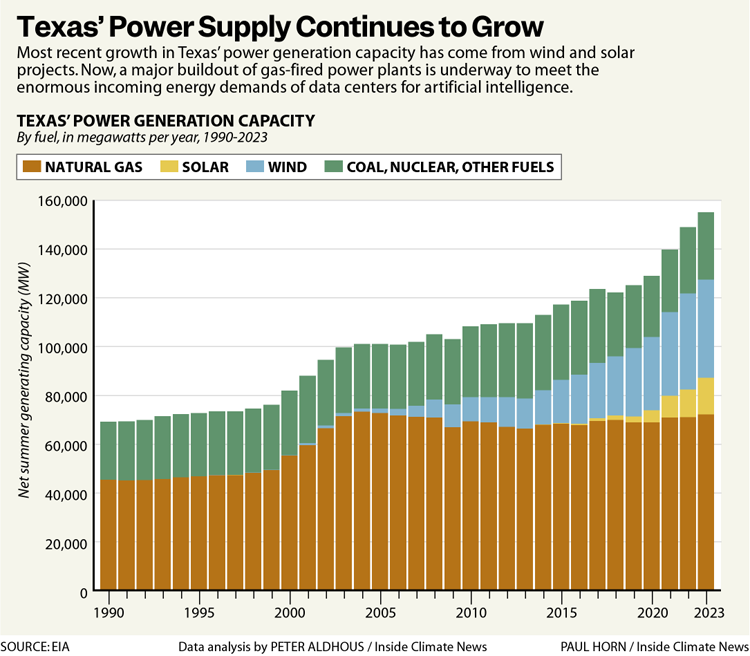

Requiring upfront payment is especially critical, senators noted, since some tech firms have abandoned data center projects, leaving local customers to bear the costs of infrastructure changes without utility companies ever generating any revenue. Communities must also consider that AI firms’ projected energy demand could severely dip if enterprise demand for AI falls short of expectations, AI capabilities “plateau” and trigger widespread indifference, AI companies shift strategies “away from scaling computer power,” or chip companies “find innovative ways to make AI more energy-efficient.”

“If data centers end up providing less business to the utility companies than anticipated, consumers could be left with massive electricity bills as utility companies recoup billions in new infrastructure costs, with nothing to show for it,” senators wrote.

Already, Utah, Oregon, and Ohio have passed laws “creating a separate class of utility customer for data centers which includes basic financial safeguards such as upfront payments and longer contract length,” senators noted, and Virginia is notably weighing a similar law.

At least one study, The New York Times noted, suggested that data centers may have recently helped reduce electricity costs by spreading the costs of upgrades over more customers, but those outcomes varied by state and could not account for future AI demand.

“It remains unclear whether broader, sustained load growth will increase long-run average costs and prices,” Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory researchers concluded. “In some cases, spikes in load growth can result in significant, near-term retail price increase.”

Until companies prove they’re paying their fair share, senators expect electricity bills to keep climbing, particularly in vulnerable areas. That will likely only increase pressure for regulators to intervene, the director of the Electricity Law Initiative at the Harvard Law School Environmental and Energy Law Program, Ari Peskoe, suggested in September.

“The utility business model is all about spreading costs of system expansion to everyone, because we all benefit from a reliable, robust electricity system,” Peskoe said. “But when it’s a single consumer that is using so much energy—basically that of an entire city—and when that new city happens to be owned by the wealthiest corporations in the world, I think it’s time to look at the fundamental assumptions of utility regulation and make sure that these facilities are really paying for all of the infrastructure costs to connect them to the system and to power them.”

Senators count the shady ways data centers pass energy costs on to Americans Read More »