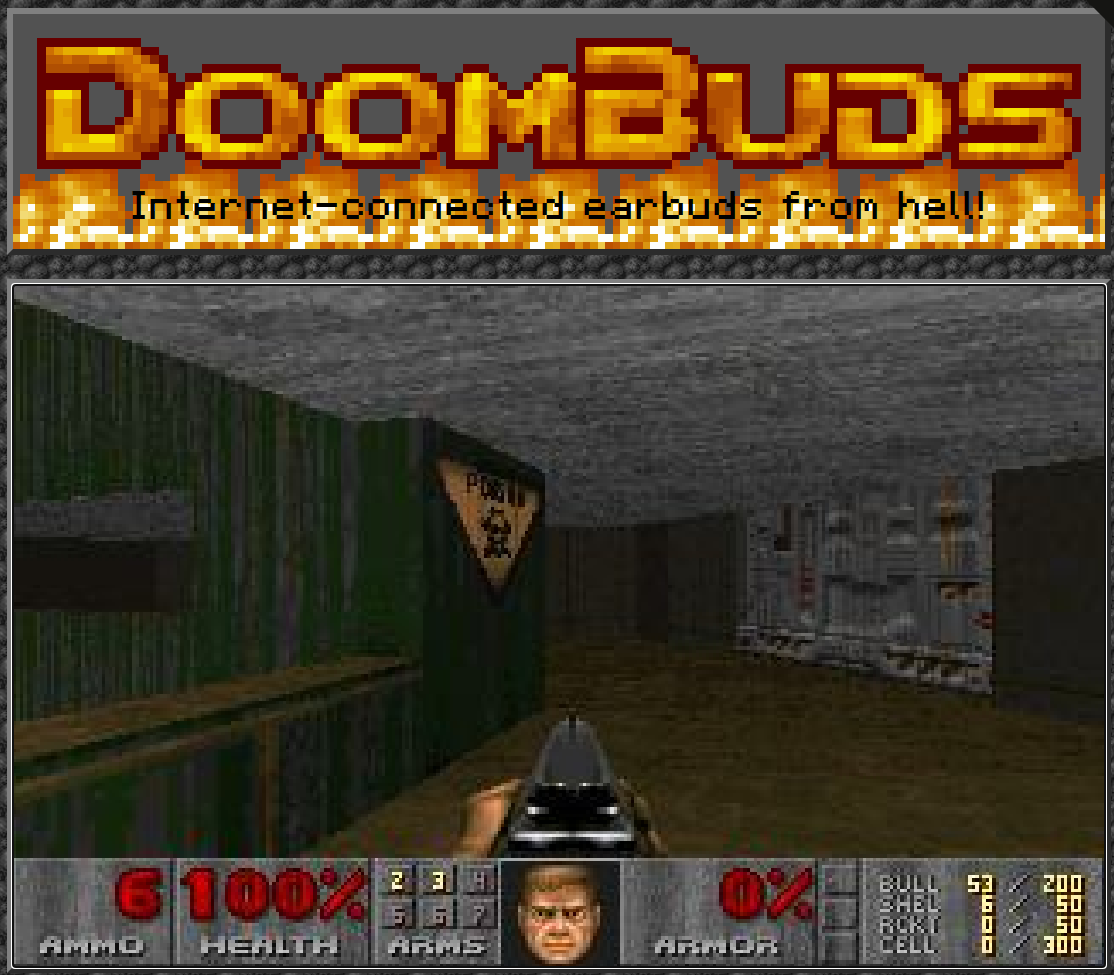

Looking back at Catacomb 3D, the game that led to Wolfenstein 3D

No longer keen on more Commander Keen

While id’s decision to lean into fast, action-oriented first-person games might seem obvious in retrospect, the video reveals that it was far from an easy decision. Catacomb 3D earned the team just $5,000 (about $11,750 in December 2025 dollars) through a contract to deliver bi-monthly games for Softdisk’s Gamer’s Edge magazine-on-a-disk. Each episode of the Commander Keen series of run-and-gun 2D games, on the other hand, was still earning “10 times that amount” at the time, Romero said.

That made sticking with Commander Keen seem like the “obvious business decision,” Romero says in the video. The team even started work on a seventh Commander Keen game—with parallax scrolling and full VGA color support—right after Catacomb 3D‘s release. At the time, it felt like Catacomb 3D might be “just like a weird gimmick thing that we did for a little bit because we wanted to play with a different technology,” as John Carmack put it.

A tech demo shows early work on Commander Keen 7 that was abandoned in favor of Wolfenstein 3D.

That feeling started to fade away, Carmack said, after his brother Adrian had an “almost falling out of his seat” moment while pivoting toward an in-game troll in Catacomb 3D. “It automatically sucked you in,” Adrian Carmack said of the feeling. “You’re trying to look behind walls, doors, whatever… you get a pop-out like that, and it was just one of the craziest things in a video game I had ever seen.”

That kind of reaction from one of their own eventually convinced the team to abandon two weeks of work on Keen 7 to focus on what would become Wolfenstein 3D. “It kind of felt that’s where the future was going,” Carmack said in the video. “[We wanted to] “take it to some place that it wouldn’t happen staying in the existing conservative [lane].”

“Within two weeks, [I was up] at one in the morning and I’m just like, ‘Guys, we need to not make this game [Keen],’” Romero told Ars in 2024. “‘This is not the future. The future is getting better at what we just did with Catacomb.’ … And everyone was immediately was like, ‘Yeah, you know, you’re right. That is the new thing, and we haven’t seen it, and we can do it, so why aren’t we doing it?’”

Looking back at Catacomb 3D, the game that led to Wolfenstein 3D Read More »