Why reviving the shuttered Anthem is turning out tougher than expected

Despite proof-of-concept video, EA’s Frostbite Engine servers are difficult to pick apart.

Anthem may be down, but it’s not quite out yet. Credit: Bioware

On January 12, EA shut down the official servers for Anthem, making Bioware’s multiplayer sci-fi adventure completely unplayable for the first time since its troubled 2019 launch. Last week, though, the Anthem community woke up to a new video showing the game at least partially loading on what appears to be a simulated background server.

The people behind that video—and the Anthem revival project that made it possible—told Ars they were optimistic about their efforts to coerce EA’s temperamental Frostbite engine into running the game without access to EA’s servers. That said, the team also wants to temper expectations that may have risen a bit too high in the wake of what is just a proof-of-concept video.

Andersson799’s early proof-of-concept video showing Anthem partially loading on emulated local servers.

“People are getting excited [about the video], and naturally people are going to get their hopes up,” project administrator Laurie told Ars. “I don’t want to be the person that’s going to have to deal with the aftermath if it turns out that we can’t actually get anywhere.”

Keep an eye on those packets

The Anthem revival effort currently centers around The Fort’s Forge, a Discord server where a handful of volunteer engineers and developers have gathered to pick apart the game and its unique architecture. Laurie said they initially set up the group “out of little more than spite for EA and Bioware around the time the shutdown got announced” back in July.

While Laurie has some experience with the community behind Gundam Evolution revival project Side 7, they knew they’d need help from people with direct experience working on EA’s Frostbite engine games. Luckily, Laurie said they were “able to catch the eyes of people who are familiar with this line of work [without] searching too much.”

One of those people was Ness199X, an experienced Frostbite tinkerer who told Ars he “never really played much Anthem” before the game’s shutdown was announced. When a friend pointed out the impending death of the title, though, Ness said he was motivated to preserve the game for posterity.

Initial efforts to examine what made Anthem tick “came up empty,” Ness said, largely because the game uses EA’s bespoke Frostbite engine differently than other EA titles. To begin mapping out those differences, Ness released a packet logger tool in September that let contributors record their own network traffic between the client and EA’s official servers. In addition to helping with reverse-engineering work, Ness writes on the Fort’s Forge Discord that players who logged their packets should be able to fully recover their characters if and when Anthem comes back in playable form.

Catching Frostbite

By analyzing that crowdsourced packet data, Ness said the Fort’s Forge team has been able to break Anthem down into three essential services:

- EA’s Blaze server: Used for basic player authentication.

- Bioware Online Services (aka BIGS): A JSON web server used to track player information like inventory and quest progression.

- The Frostbite multiplayer engine: Loads level data and tracks the real-time positions of players and non-player characters in those levels.

Early efforts to emulate the Blaze and BIGS portions of that architecture helped lead directly to last week’s proof-of-concept video. Andersson799—who says he’s been tinkering with Battlefield and other Frostbite games since 2015—said he was quickly able to use his own logged Anthem packets to create a “barebones anthem private server” that served as a “quick and dirty” sample that he decided to share via YouTube.

“I basically made the tool to just simply reply with the packet captures that I got,” Andersson told me. That was enough to “get in to the game with player profiles loaded and everything.” And while Ness says there’s still some effort needed “to [make Blaze and BIGS] work well and smoothly in terms of quest progression, etc.,” the path forward on those portions is relatively straightforward.

It’s the Frostbite engine and its odd client-server architecture that forms the biggest barrier to getting Anthem up and running again without EA’s servers. “Due to how Frostbite is designed, all gameplay in a Frostbite game runs in a ‘server’ context,” Ness explained. Even in a single-player game like Mass Effect: Andromeda, he said, “the client just creates a separate server thread and pipes all the traffic internally.”

“I feel like with Anthem, it heavily relies on online data that was stored in Bioware’s server,” Andersson added. “In my initial testing, the game couldn’t load into the level without that data.”

Anthem‘s Fort Tarsis area loads its data from local files, rather than EA’s servers.

There’s some hope that this crucial level data is still available and recoverable, though. Ness points out that Fort Tarsis, the game’s lobby area, already runs using offline data piped through a local “server” thread, meaning the rest of the game could theoretically be coerced to run similarly.

Just as important, he says, “as far as we have been able to discern, all the logic for the other levels, which when the game was live ran on a remote server, also exists in the client,” Ness said. “By patching the game we can most likely enable the ability to host these in process as well. That’s what we’re exploring.”

“To be honest we’re not entirely sure…”

While all that local level data should be usable in theory, seemingly random differences between Anthem and other Frostbite games are getting in the way of loading the data in practice. Anthem acts like a standard Frostbite game “for the most part,” Ness said, but at times will show unusual behaviors that are hard to pin down.

“For example, when we try to load most maps, no NPCs spawn, but in some maps they do,” he said. “And we have yet to determine why. Ness has some suspicion that the odd behavior is connected to the “fairly extensive amount of player data the game keeps as part of its online RPG nature,” but adds that “to be honest we’re not entirely sure how deep the differences go, other than that the engine didn’t behave how we expected it to.”

Ness said he’s about 75 percent confident that the team will be able to figure out how to fully leverage the Frostbite engine to power a version of the game that runs without EA’s centralized servers. If that effort succeeds, he says a playable version of Anthem could be back up and running in “months, or less even, depending on motivation.” But if the efforts to pick apart Anthem’s take on Frostbite hits a brick wall, Ness says “the amount of work increases fairly exponentially and I’m a lot less confident that we have the motivation for that.”

“I’m fairly confident that we can get this game to be playable again, like how it is supposed to be,” Andersson said. “It’ll just take time as most of us have our own life to manage besides this.”

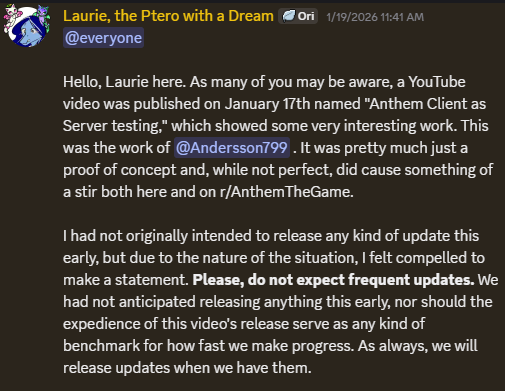

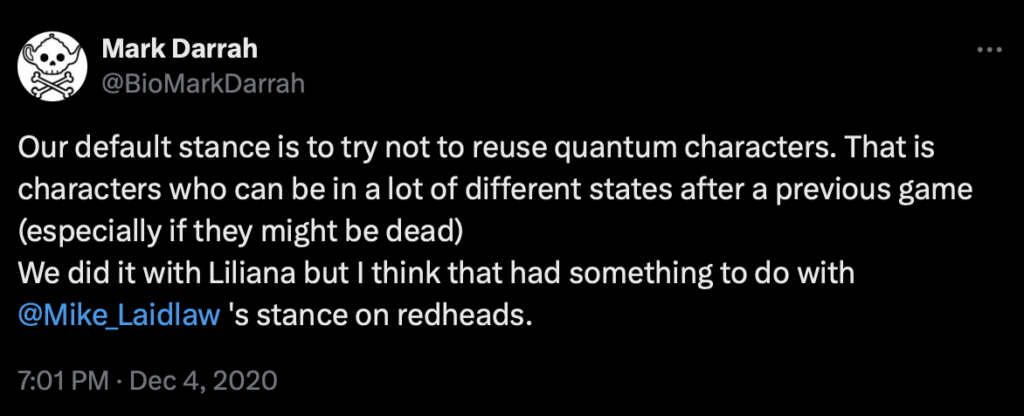

Engaging in some expectations management on the Fort’s Forge Discord. Credit: Laurie / The Fort’s Forge

In the meantime, Laurie is still trying to manage expectations set by the somewhat premature posting of Andersson’s proof-of-concept video. “Please, do not expect frequent updates,” Laurie wrote in the Fort’s Forge Discord. “We had not anticipated releasing anything this early, nor should the expedience of this video’s release serve as any kind of benchmark for how fast we make progress.”

Laurie also took to Reddit to publicly call the video “a really hacky thing so I want to ask people to manage their expectations just a bit. A lot of stuff clearly doesn’t work as ‘intended,’ and definitely needs at minimum, more polish.”

At one point last week, Laurie says they had to stop accepting new members to the Fort’s Forge Discord, “mostly to prevent an influx of people in response to… news coverage.” And while people with Frostbite engine modding experience are encouraged to reach out, the small team is being cautious about growing too large, too fast.

“We’re a little reluctant to add developers right now as we have no real code base to work from,” Ness said, describing their current efforts as “scratch work” maintained in separate forms by multiple people. “But once we firm that up (hopefully in the next weeks), we will look to add more [coders].”

Kyle Orland has been the Senior Gaming Editor at Ars Technica since 2012, writing primarily about the business, tech, and culture behind video games. He has journalism and computer science degrees from University of Maryland. He once wrote a whole book about Minesweeper.

Why reviving the shuttered Anthem is turning out tougher than expected Read More »