Meta hypes AI friends as social media’s future, but users want real connections

If you ask the man who has largely shaped how friends and family connect on social media over the past two decades about the future of social media, you may not get a straight answer.

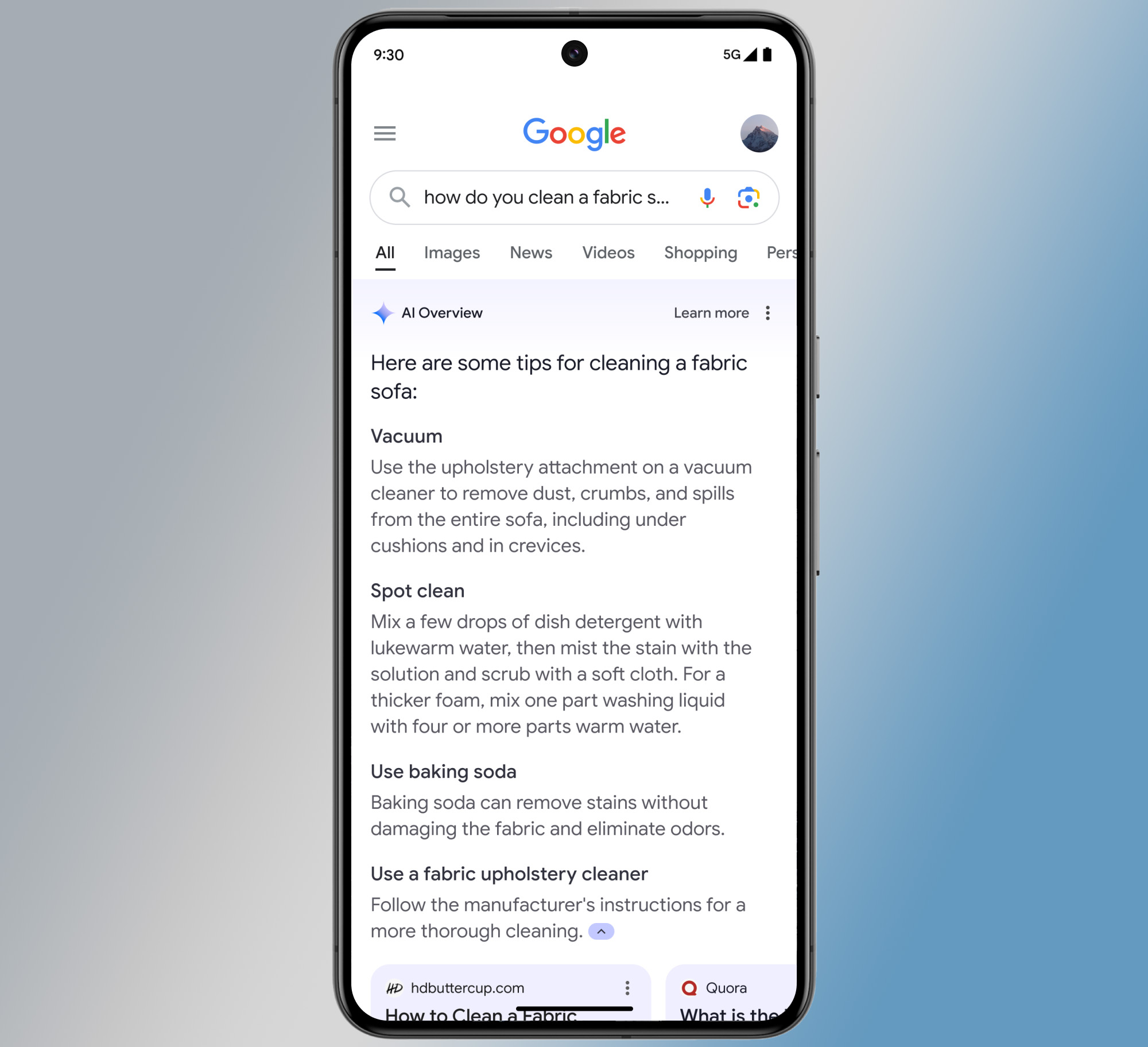

At the Federal Trade Commission’s monopoly trial, Meta CEO Mark Zuckerberg attempted what seemed like an artful dodge to avoid criticism that his company allegedly bought out rivals Instagram and WhatsApp to lock users into Meta’s family of apps so they would never post about their personal lives anywhere else. He testified that people actually engage with social media less often these days to connect with loved ones, preferring instead to discover entertaining content on platforms to share in private messages with friends and family.

As Zuckerberg spins it, Meta no longer perceives much advantage in dominating the so-called personal social networking market where Facebook made its name and cemented what the FTC alleged is an illegal monopoly.

“Mark Zuckerberg says social media is over,” a New Yorker headline said about this testimony in a report noting a Meta chart that seemed to back up Zuckerberg’s words. That chart, shared at the trial, showed the “percent of time spent viewing content posted by ‘friends'” had declined over the past two years, from 22 to 17 percent on Facebook and from 11 to 7 percent on Instagram.

Supposedly because of this trend, Zuckerberg testified that “it doesn’t matter much” if someone’s friends are on their preferred platform. Every platform has its own value as a discovery engine, Zuckerberg suggested. And Meta platforms increasingly compete on this new playing field against rivals like TikTok, Meta argued, while insisting that it’s not so much focused on beating the FTC’s flagged rivals in the connecting-friends-and-family business, Snap and MeWe.

But while Zuckerberg claims that hosting that kind of content doesn’t move the needle much anymore, owning the biggest platforms that people use daily to connect with friends and family obviously still matters to Meta, MeWe founder Mark Weinstein told Ars. And Meta’s own press releases seem to back that up.

Weeks ahead of Zuckerberg’s testimony, Meta announced that it would bring back the “magic of friends,” introducing a “friends” tab to Facebook to make user experiences more like the original Facebook. The company intentionally diluted feeds with creator content and ads for the past two years, but it now appears intent on trying to spark more real conversations between friends and family, at least partly to fuel its newly launched AI chatbots.

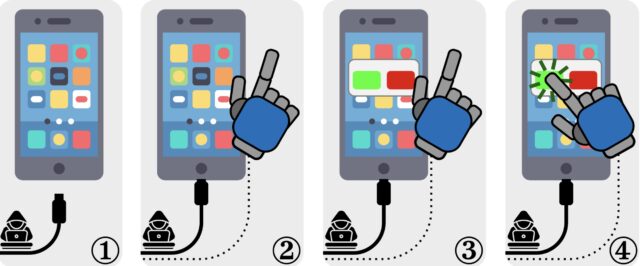

Those chatbots mine personal information shared on Facebook and Instagram, and Meta wants to use that data to connect more personally with users—but “in a very creepy way,” The Washington Post wrote. In interviews, Zuckerberg has suggested these AI friends could “meaningfully” fill the void of real friendship online, as the average person has only three friends but “has demand” for up to 15. To critics seeking to undo Meta’s alleged monopoly, this latest move could signal a contradiction in Zuckerberg’s testimony, showing that the company is so invested in keeping users on its platforms that it’s now creating AI friends (wh0 can never leave its platform) to bait the loneliest among us into more engagement.

“The average person wants more connectivity, connection, than they have,” Zuckerberg said, hyping AI friends. For the Facebook founder, it must be hard to envision a future where his platforms aren’t the answer to providing that basic social need. All this comes more than a decade after he sought $5 billion in Facebook’s 2012 initial public offering so that he could keep building tools that he told investors would expand “people’s capacity to build and maintain relationships.”

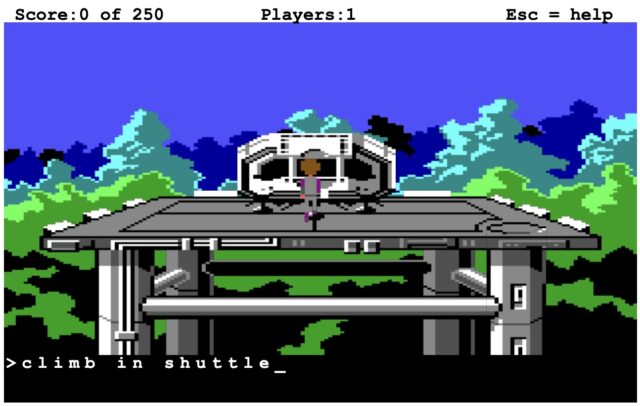

At the trial, Zuckerberg testified that AI and augmented reality will be key fixtures of Meta’s platforms in the future, predicting that “several years from now, you are going to be scrolling through your feed, and not only is it going to be sort of animated, but it will be interactive.”

Meta declined to comment further on the company’s vision for social media’s future. In a statement, a Meta spokesperson told Ars that “the FTC’s lawsuit against Meta defies reality,” claiming that it threatens US leadership in AI and insisting that evidence at trial would establish that platforms like TikTok, YouTube, and X are Meta’s true rivals.

“More than 10 years after the FTC reviewed and cleared our acquisitions, the Commission’s action in this case sends the message that no deal is ever truly final,” Meta’s spokesperson said. “Regulators should be supporting American innovation rather than seeking to break up a great American company and further advantaging China on critical issues like AI.”

Meta faces calls to open up its platforms

Weinstein, the MeWe founder, told Ars that back in the 1990s when the original social media founders were planning the first community portals, “it was so beautiful because we didn’t think about bots and trolls. We didn’t think about data mining and surveillance capitalism. We thought about making the world a more connected and holistic place.”

But those who became social media overlords found more money in walled gardens and increasingly cut off attempts by outside developers to improve the biggest platforms’ functionality or leverage their platforms to compete for their users’ attention. Born of this era, Weinstein expects that Zuckerberg, and therefore Meta, will always cling to its friends-and-family roots, no matter which way Zuckerberg says the wind is blowing.

Meta “is still entirely based on personal social networking,” Weinstein told Ars.

In a Newsweek op-ed, Weinstein explained that he left MeWe in 2021 after “competition became impossible” with Meta. It was a time when MeWe faced backlash over lax content moderation, drawing comparisons between its service and right-wing apps like Gab or Parler. Weinstein rejected those comparisons, seeing his platform as an ideal Facebook rival and remaining a board member through the app’s more recent shift to decentralization. Still defending MeWe’s failed efforts to beat Facebook, he submitted hundreds of documents and was deposed in the monopoly trial, alleging that Meta retaliated against MeWe as a privacy-focused rival that sought to woo users away by branding itself the “anti-Facebook.”

Among his complaints, Weinstein accused Meta of thwarting MeWe’s attempts to introduce interoperability between the two platforms, which he thinks stems from a fear that users might leave Facebook if they discover a more appealing platform. That’s why he’s urged the FTC—if it wins its monopoly case—to go beyond simply ordering a potential breakup of Facebook, Instagram, and WhatsApp to also require interoperability between Meta’s platforms and all rivals. That may be the only way to force Meta to release its clutch on personal data collection, Weinstein suggested, and allow for more competition broadly in the social media industry.

“The glue that holds it all together is Facebook’s monopoly over data,” Weinstein wrote in a Wall Street Journal op-ed, recalling the moment he realized that Meta seemed to have an unbeatable monopoly. “Its ownership and control of the personal information of Facebook users and non-users alike is unmatched.”

Cory Doctorow, a special advisor to the Electronic Frontier Foundation, told Ars that his vision of a better social media future goes even further than requiring interoperability between all platforms. Social networks like Meta’s should also be made to allow reverse engineering so that outside developers can modify their apps with third-party tools without risking legal attacks, he said.

Doctorow said that solution would create “an equilibrium where companies are more incentivized to behave themselves than they are to cheat” by, say, retaliating against, killing off, or buying out rivals. And “if they fail to respond to that incentive and they cheat anyways, then the rest of the world still has a remedy,” Doctorow said, by having the choice to modify or ditch any platform deemed toxic, invasive, manipulative, or otherwise offensive.

Doctorow summed up the frustration that some users have faced through the ongoing “enshittification” of platforms (a term he coined) ever since platforms took over the Internet.

“I’m 55 now, and I’ve gotten a lot less interested in how things work because I’ve had too many experiences with how things fail,” Doctorow told Ars. “And I just want to make sure that if I’m on a service and it goes horribly wrong, I can leave.”

Social media haters wish OG platforms were doomed

Weinstein pointed out that Meta’s alleged monopoly impacts a group often left out of social media debates: non-users. And if you ask someone who hates social media what the future of social media should look like, they will not mince words: They want a way to opt out of all of it.

As Meta’s monopoly trial got underway, a personal blog post titled “No Instagram, no privacy” rose to the front page of Hacker News, prompting a discussion about social media norms and reasonable expectations for privacy in 2025.

In the post, Wouter-Jan Leys, a privacy advocate, explained that he felt “blessed” to have “somehow escaped having an Instagram account,” feeling no pressure to “update the abstract audience of everyone I ever connected with online on where I am, what I am doing, or who I am hanging out with.”

But despite never having an account, he’s found that “you don’t have to be on Instagram to be on Instagram,” complaining that “it bugs me” when friends seem to know “more about my life than I tell them” because of various friends’ posts that mention or show images of him. In his blog, he defined privacy as “being in control of what other people know about you” and suggested that because of platforms like Instagram, he currently lacked this control. There should be some way to “fix or regulate this,” Leys suggested, or maybe some universal “etiquette where it’s frowned upon to post about social gatherings to any audience beyond who already was at that gathering.”

On Hacker News, his post spurred a debate over one of the longest-running privacy questions swirling on social media: Is it OK to post about someone who abstains from social media?

Some seeming social media fans scolded Leys for being so old-fashioned about social media, suggesting, “just live your life without being so bothered about offending other people” or saying that “the entire world doesn’t have to be sanitized to meet individual people’s preferences.” Others seemed to better understand Leys’ point of view, with one agreeing that “the problem is that our modern norms (and tech) lead to everyone sharing everything with a large social network.”

Surveying the lively thread, another social media hater joked, “I feel vindicated for my decision to entirely stay off of this drama machine.”

Leys told Ars that he would “absolutely” be in favor of personal social networks like Meta’s platforms dying off or losing steam, as Zuckerberg suggested they already are. He thinks that the decline in personal post engagement that Meta is seeing is likely due to a combination of factors, where some users may prefer more privacy now after years of broadcasting their lives, and others may be tired of the pressure of building a personal brand or experiencing other “odd social dynamics.”

Setting user sentiments aside, Meta is also responsible for people engaging with fewer of their friends’ posts. Meta announced that it would double the amount of force-fed filler in people’s feeds on Instagram and Facebook starting in 2023. That’s when the two-year span begins that Zuckerberg measured in testifying about the sudden drop-off in friends’ content engagement.

So while it’s easy to say the market changed, Meta may be obscuring how much it shaped that shift. Degrading the newsfeed and changing Instagram’s default post shape from square to rectangle seemingly significantly shifted Instagram social norms, for example, creating an environment where Gen Z users felt less comfortable posting as prolifically as millennials did when Instagram debuted, The New Yorker explained last year. Where once millennials painstakingly designed immaculate grids of individual eye-catching photos to seem cool online, Gen Z users told The New Yorker that posting a single photo now feels “humiliating” and like a “social risk.”

But rather than eliminate the impulse to post, this cultural shift has popularized a different form of personal posting: staggered photo dumps, where users wait to post a variety of photos together to sum up a month of events or curate a vibe, the trend piece explained. And Meta is clearly intent on fueling that momentum, doubling the maximum number of photos that users can feature in a single post to encourage even more social posting, The New Yorker noted.

Brendan Benedict, an attorney for Benedict Law Group PLLC who has helped litigate big tech antitrust cases, is monitoring the FTC monopoly trial on a Substack called Big Tech on Trial. He told Ars that the evidence at the trial has shown that “consumers want more friends and family content, and Meta is belatedly trying to address this” with features like the “friends” tab, while claiming there’s less interest in this content.

Leys doesn’t think social media—at least the way that Facebook defined it in the mid-2000s—will ever die, because people will never stop wanting social networks like Facebook or Instagram to stay connected with all their friends and family. But he could see a world where, if people ever started truly caring about privacy or “indeed [got] tired of the social dynamics and personal brand-building… the kind of social media like Facebook and Instagram will have been a generational phenomenon, and they may not immediately bounce back,” especially if it’s easy to switch to other platforms that respond better to user preferences.

He also agreed that requiring interoperability would likely lead to better social media products, but he maintained that “it would still not get me on Instagram.”

Interoperability shakes up social media

Meta thought it may have already beaten the FTC’s monopoly case, filing for a motion for summary judgment after the FTC rested its case in a bid to end the trial early. That dream was quickly dashed when the judge denied the motion days later. But no matter the outcome of the trial, Meta’s influence over the social media world may be waning just as it’s facing increasing pressure to open up its platforms more than ever.

The FTC has alleged that Meta weaponized platform access early on, only allowing certain companies to interoperate and denying access to anyone perceived as a threat to its alleged monopoly power. That includes limiting promotions of Instagram to keep users engaged with Facebook Blue. A primary concern for Meta (then Facebook), the FTC claimed, was avoiding “training users to check multiple feeds,” which might allow other apps to “cannibalize” its users.

“Facebook has used this power to deter and suppress competitive threats to its personal social networking monopoly. In order to protect its monopoly, Facebook adopted and required developers to agree to conditional dealing policies that limited third-party apps’ ability to engage with Facebook rivals or to develop into rivals themselves,” the FTC alleged.

By 2011, the FTC alleged, then-Facebook had begun terminating API access to any developers that made it easier to export user data into a competing social network without Facebook’s permission. That practice only ended when the UK parliament started calling out Facebook’s anticompetitive conduct toward app developers in 2018, the FTC alleged.

According to the FTC, Meta continues “to this day” to “screen developers and can weaponize API access in ways that cement its dominance,” and if scrutiny ever subsides, Meta is expected to return to such anticompetitive practices as the AI race heats up.

One potential hurdle for Meta could be that the push for interoperability is not just coming from the FTC or lawmakers who recently reintroduced bipartisan legislation to end walled gardens. Doctorow told Ars that “huge public groundswells of mistrust and anger about excessive corporate power” that “cross political lines” are prompting global antitrust probes into big tech companies and are perhaps finally forcing a reckoning after years of degrading popular products to chase higher and higher revenues.

For social media companies, mounting concerns about privacy and suspicions about content manipulation or censorship are driving public distrust, Doctorow said, as well as fears of surveillance capitalism. The latter includes theories that Doctorow is skeptical of. Weinstein embraced them, though, warning that platforms seem to be profiting off data without consent while brainwashing users.

Allowing users to leave the platform without losing access to their friends, their social posts, and their messages might be the best way to incentivize Meta to either genuinely compete for billions of users or lose them forever as better options pop up that can plug into their networks.

In his Newsweek op-ed, Weinstein suggested that web inventor Tim Berners-Lee has already invented a working protocol “to enable people to own, upload, download, and relocate their social graphs,” which maps users’ connections across platforms. That could be used to mitigate “the network effect” that locks users into platforms like Meta’s “while interrupting unwanted data collection.”

At the same time, Doctorow told Ars that increasingly popular decentralized platforms like Bluesky and Mastodon already provide interoperability and are next looking into “building interoperable gateways” between their services. Doctorow said that communicating with other users across platforms may feel “awkward” at first, but ultimately, it may be like “having to find the diesel pump at the gas station” instead of the unleaded gas pump. “You’ll still be going to the same gas station,” Doctorow suggested.

Opening up gateways into all platforms could be useful in the future, Doctorow suggested. Imagine if one platform goes down—it would no longer disrupt communications as drastically, as users could just pivot to communicate on another platform and reach the same audience. The same goes for platforms that users grow to distrust.

The EFF supports regulators’ attempts to pass well-crafted interoperability mandates, Doctorow said, noting that “if you have to worry about your users leaving, you generally have to treat them better.”

But would interoperability fix social media?

The FTC has alleged that “Facebook’s dominant position in the US personal social networking market is durable due to significant entry barriers, including direct network effects and high switching costs.”

Meta disputes the FTC’s complaint as outdated, arguing that its platform could be substituted by pretty much any social network.

However, Guy Aridor, a co-author of a recent article called “The Economics of Social Media” in the Journal of Economic Literature, told Ars that dominant platforms are probably threatened by shifting social media trends and are likely to remain “resistant to interoperability” because “it’s in the interest of the platform to make switching and coordination costs high so that users are less likely to migrate away.” For Meta, research shows its platforms’ network effects have appeared to weaken somewhat but “clearly still exist” despite social media users increasingly seeking content on platforms rather than just socialization, Aridor said.

Interoperability advocates believe it will make it easier for startups to compete with giants like Meta, which fight hard and sometimes seemingly dirty to keep users on their apps. Reintroducing the ACCESS Act, which requires platform compatibility to enable service switching, Senator Mark R. Warner (D-Va.) said that “interoperability and portability are powerful tools to promote innovative new companies and limit anti-competitive behaviors.” He’s hoping that passing these “long-overdue requirements” will “boost competition and give consumers more power.”

Aridor told Ars it’s obvious that “interoperability would clearly increase competition,” but he still has questions about whether users would benefit from that competition “since one consistent theme is that these platforms are optimized to maximize engagement, and there’s numerous empirical evidence we have by now that engagement isn’t necessarily correlated with utility.”

Consider, Aridor suggested, how toxic content often leads to high engagement but lower user satisfaction, as MeWe experienced during its 2021 backlash.

Aridor said there is currently “very little empirical evidence on the effects of interoperability,” but theoretically, if it increased competition in the current climate, it would likely “push the market more toward supplying engaging entertainment-related content as opposed to friends and family type of content.”

Benedict told Ars that a remedy like interoperability would likely only be useful to combat Meta’s alleged monopoly following a breakup, which he views as the “natural remedy” following a potential win in the FTC’s lawsuit.

Without the breakup and other meaningful reforms, a Meta win could preserve the status quo and see the company never open up its platforms, perhaps perpetuating Meta’s influence over social media well into the future. And if Zuckerberg’s vision comes to pass, instead of seeing what your friends are posting on interoperating platforms across the Internet, you may have a dozen AI friends trained on your real friends’ behaviors sending you regular dopamine hits to keep you scrolling on Facebook or Instagram.

Aridor’s team’s article suggested that, regardless of user preferences, social media remains a permanent fixture of society. If that’s true, users could get stuck forever using whichever platforms connect them with the widest range of contacts.

“While social media has continued to evolve, one thing that has not changed is that social media remains a central part of people’s lives,” his team’s article concluded.

Meta hypes AI friends as social media’s future, but users want real connections Read More »