Ars Technica’s top 20 video games of 2024

A relatively light year still had its fair share of interactive standouts.

Credit: Aurich Lawson | Getty Images

When we introduced last year’s annual list of the best games in this space, we focused on how COVID delays led to a 2023 packed with excellent big-name blockbusters and intriguing indies that seemed to come out of nowhere. The resulting flood of great titles made it difficult to winnow the year’s best down to our traditional list of 20 titles.

In 2024 we had something close to the opposite problem. While there were definitely a few standout titles that were easy to include on this year’s list (Balatro, UFO 50, and Astro Bot likely chief among them), rounding out the list to a full 20 proved more challenging than it has in perhaps any other year during my tenure at Ars Technica (way back in 2012!). The games that ended up on this year’s list are all strong recommendations, for sure. But many of them might have had more trouble making a Top 20 list in a packed year like 2023.

We’ll have to wait to see if the release calendar seesaws back to a quality-packed one in 2025, but the forecast for big games like Civilization 7, Avowed, Doom: The Dark Ages, Grand Theft Auto 6, and many, many more has us thinking that it might. In the meantime, here are our picks for the 20 best games that came out in 2024, in alphabetical order.

Animal Well

Billy Basso; Windows, PS5, Xbox X/S, Switch

The Metroidvania genre has started to feel a little played out of late. Go down this corridor, collect that item, go back to the wall that can only be destroyed by said item, explore a new corridor for the next item, etc. Repeat until you’ve seen the entire map or get too bored to continue.

Animal Well eschews this paint-by-numbers design and brings back the sense of mystery inherent to the best games in the genre. This is done in part by some masterful pixel-art graphics, which incorporate some wild 2D lighting effects and detailed, painterly sprite world. The animations—from subtle movements of the lowliest flower to terrifying, screen-filling actions from the game’s titular giant animals—are handled with equal aplomb.

But Animal Well really shines in its often inscrutable map and item design. Many key items in the game have multiple uses that aren’t fully explained in the game itself, requiring a good deal of guessing, checking, and observation to figure out how to exploit fully. Uncovering the arcane secrets of the game’s multiple environmental blocks is often far from obvious and rewards players who like to experiment and explore.

Those arcane secrets can sometimes seem too obtuse for their own good—don’t be surprised if you have to consult an outside walkthrough or work with someone to bust past some of the most inscrutable barriers put in your way. If you soldier through, though, you’ll have been on one of the most memorable journeys of its type.

-Kyle Orland

Astro Bot

Team Asobi; PS5

Astro Bot is an unlikely success story. The team that made it, Studio Asobi, was for years dedicated to making small-scale projects that were essentially glorified tech demos for Sony’s latest hardware. First there was The Playroom, which was just a collection of small experiences made to show off the features of the PlayStation 4’s camera peripheral. Then there was Astro Bot Rescue Mission, which acted as a showcase for the first PlayStation VR headset.

But momentum really picked up with Astro’s Playroom, the bite-size 2020 3D platformer that was bundled with every PlayStation 5—again to show off the hardware features. When I played it, my main thought was, “I really wish this team would make a full-blown game.”

That’s exactly what Astro Bot is: a 15-hourlong 3D platformer with AAA production values, with no goal other than just being an excellent game. Like its predecessors, it fully leverages all the hardware features of the PlayStation 5, and it’s loaded with Easter eggs and fan service for players who’ve been playing PlayStation consoles for three decades.

Like many 3D platformers, it’s a collect-a-thon. In this case, you’re gathering more than 300 little robot friends. All of them are modeled after characters from other games that defined the PlayStation platform, from Resident Evil to Ico to The Last of Us, from the obscure to the well-known.

Between those Easter eggs, the tightly designed gameplay, and the upbeat music, there’s an ever-present air of joy and celebration in Astro Bot—especially for players who get the references. But even if you’ve never played any of the games it draws on, it’s an excellent 3D platformer—perhaps the best released on any platform in the seven years since 2017’s Super Mario Odyssey.

The PlayStation 5 will arguably be best remembered for beefy open-world games, serious narrative titles, and multiplayer shooters. Amid all that, I don’t think anybody expected one of the best games ever released for the console to be a platformer that in some ways would feel more at home on the PlayStation 2—but that’s what happened, and I’m grateful for the time I spent with it.

The only negative thing I have to say about it is that because of how it leverages the specific features of the DualSense controller, it’s hard to imagine it’ll ever be playable for anyone who doesn’t own that device.

Is it worth buying a PS5 just to play Astro Bot? Probably not—as beefy as it is compared to Astro’s Playroom, there’s not enough here to justify that. But if you have one and you haven’t played it yet, get on it, because you’re missing out.

-Samuel Axon

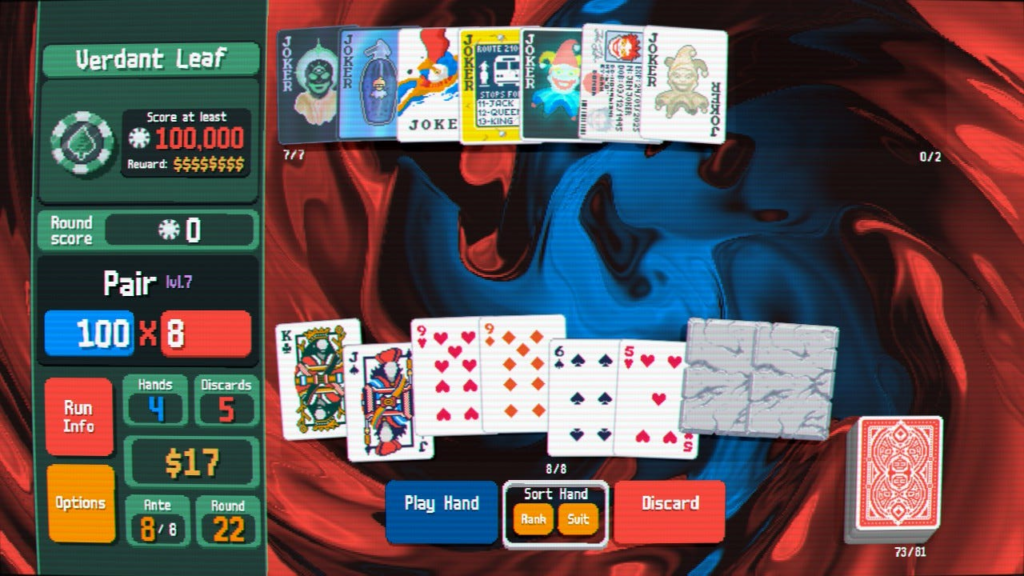

Balatro

LocalThunk; Windows, PS4/5, Xbox One/Series, Switch, MacOS, iOS, Android

At first glance, video poker probably seems a bit too random to serve as the basis of yet another rogue-like deck-builder experience. As anyone who’s been to Atlantic City can tell you, video poker’s hold-and-draw hand-building involves only the barest hint of strategy and is designed so the house always wins.

The genius of Balatro, then, is in the layers of strategy it adds to this simple, easy-to-grasp poker hand base. The wide variety of score or hand-modifying jokers that you purchase in between hands can be arranged in literally millions of combinations, each of which can change the way a particular run goes in ways both large and small. Even the most powerful jokers can become nearly useless if you run into the wrong debuffing Boss Blind, forcing you to modify your strategy mid-run to keep the high-scoring poker hands coming.

Then you add in a complex in-game economy, powerful deck-altering arcana cards, dozens of Deck and Stake difficulty options, and a Challenge Mode whose hardest options have continued to thwart me even after well over 100 hours of play. The result is a game that’s instantly compelling and as addictive as a heater at a casino, only without the potential to lose your mortgage payment to a series of bad bets.

-Kyle Orland

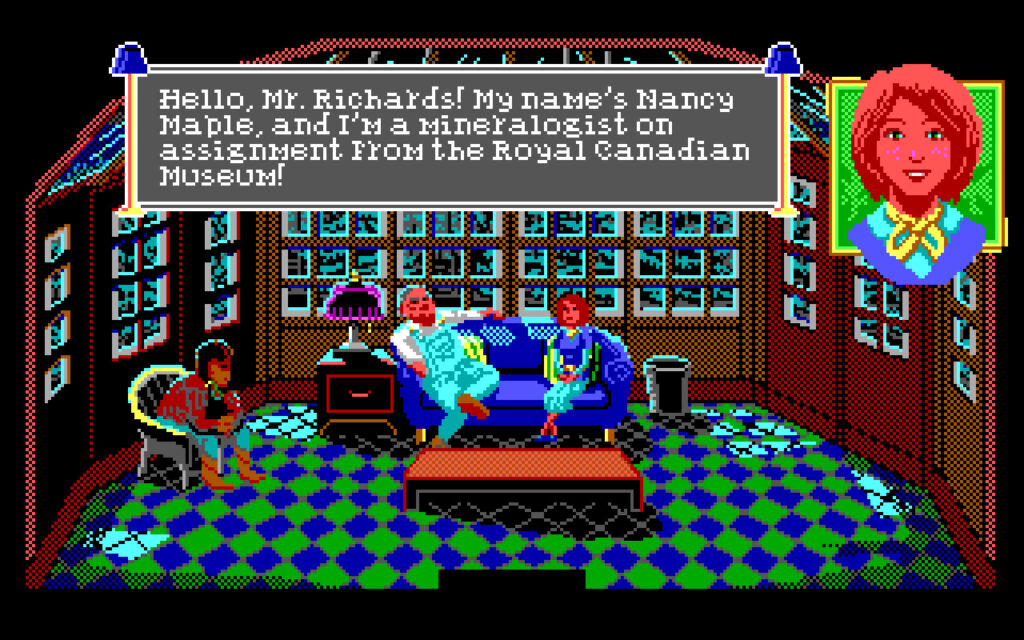

The Crimson Diamond

Julia Minamata; Windows, Mac

Would you like to spend some time in a rural vacation town in Ontario, Canada, doing mineralogy fieldwork in the off-season? A better question, then: Would you like to go there in 16-color EGA, wandering through a classic adventure game, text parser and all?

The Crimson Diamond is one of the most intriguing gaming trips I took this year. It’s an achievement in creative constraints, a cozy mystery, and an ear-catching soundtrack. It was made by a solo Canadian developer, inside Adventure Game Studio, with some real work put into upgrading the text parser and (optional) mouse experience with reasonable quality-of-life concessions. The charming but mysterious plot gently pulls you along from one wonderfully realized 1980s-era IBM backdrop to the next. It feels like playing a game you forgot to unbox, except this one actually plays without a dozen compatibility tricks.

We are awash in game remasters and light remakes that toy with our memories of old systems and forgotten genres (and having a lot more time to play games). The Crimson Diamond does something much more interesting, finding just the right new story and distinct style to port backward to a bygone era. It’s worth the clicks for any fan of pointing, clicking, and investigating.

-Kevin Purdy

Elden Ring: Shadow of the Erdtree

From Software; Windows, PS4/5, Xbox One/Series

Credit: Bandai Namco

You can tell downloadable content has come a long way when we deign to put a piece of DLC on our best-games-of-the-year list in 2024.

Released two years after the megaton zeitgeist hit that was the original Elden Ring, Shadow of the Erdtree bucks just as many modern gaming conventions as its base game did. Yes, it’s DLC because it’s digitally distributed add-on content, but while most AAA games get DLC that adds about 5–10 hours of stuff to do, Shadow of the Erdtree‘s scope actually fell somewhere between a full sequel and the expansions you’d buy in separate retail boxes for PC games in the 1990s and 2000s. It adds a large new landmass to explore, with multiple additional “legacy dungeons” and tentpole bosses, plus new mechanics and weapons aplenty.

Additionally, the game’s designers cleverly mapped a whole new system on top of the base game’s player levels and equipment, ensuring that you could still get the same satisfying sense of power progression, regardless of how deeply you’d gotten into the Elden Ring base game previously. Shadow of the Erdtree attracted some criticism for its sharp difficulty—even more so than the base game—but the same satisfying progression from hopelessness to triumph through perseverance as we enjoyed in 2022 is in play here.

As such, everything that was great about Elden Ring is also great about Shadow of the Erdtree. You could cynically call it more of the same, but when what we’re getting more of is so delicious, it’s hard to complain—especially given that this expansion includes some of the most compelling and original bosses in From Software history.

It didn’t convert anyone who didn’t dig the original, but fortunately that still left it with an audience of millions of people who were excited for a new challenge. Its impressive polish and scope land it on this list.

-Samuel Axon

Frostpunk 2

11 bit studios; Windows, Mac (ARM-based); PlayStation, Xbox (coming in 2025)

Credit: 11 Bit Studios

The first Frostpunk asked if you could make the terrible decisions necessary for survival in a never-ending blizzard. Frostpunk 2 asks you to manage something different, but no less dire: helping these people who managed to hold on keep their nascent civilization together. You can go deep with the fascists, the mystics, the hard-nosed realists, or the science nerds or try to play them all off one another to keep the furnace going.

It’s stressful, and it’s not at all easy, and the developers may have done too good a job of recreating the insane demands and interplay of human factions. The interface and navigation, sore spots on launch, have received a lot of attention, and the roadmap for the game into 2025 looks intriguing. I’d probably recommend starting with the first game before diving into this, but Frostpunk 2 is an accomplished, confident game in its own right. Human failings amidst an unfeeling snowpocalypse make for some engaging scenes.

-Kevin Purdy

Halls of Torment

Chasing Carrots; Windows, Linux, iOS, Android

Credit: Chasing Carrots

The isometric demon-killing of the old-school Diablo games has endured over the decades, especially among those who remember playing in their youth. But the whole concept has been in need of a bit of an update now that we’re in the age of Vampire Survivors and its “Bullet Heaven” auto-shooter ilk.

Enter Halls of Torment, a game that is probably as close as it comes to aping old-school Diablo‘s visual style without being legally actionable. Here, though, all the lore and story and exploration of the Diablo games has been replaced by a lot more enemies, all streaming toward your protagonist at the rate of up to 50,000 per hour. Much like Vampire Survivors, the name of the game here is dodging through those small holes in those swarms of enemies while your character automatically fills the screen with devastating attacks (that slowly level up as you play).

The wide variety of different playable classes—each with their own distinct strengths, weaknesses, and unique attack patterns—help each run feel distinct, even after you’ve smashed through the game’s limited set of six environments. But there’s plenty of cathartic replay value here for anyone who just wants to cause as much on-screen carnage as possible in a very short period of time.

-Kyle Orland

Helldivers 2

Arrowhead Game Studios; Windows, PS5

Credit: PlayStation/Arrowhead

Every so often, a multiplayer game releases to almost universal praise, and for a few months, seemingly everyone is talking about it. This year, that game was Helldivers 2. The game converted the 2015 original’s top-down shoot-em-up gameplay into third-person shooter action, and the switch-up was enough to bring in tons of players. Taking more than a few cues from Starship Troopers, the game asks you to “spread democracy” throughout the galaxy by mowing down hordes of alien bugs or robots during short-ish missions on various planets. Work together with your team, and the rest of the player base, to slowly liberate the galaxy.

I played Helldivers 2 mostly as a “hang out game,” something to do with my hands and eyes as I chatted with friends. You can play the game “seriously,” I guess, but that would be missing the point for me. My favorite part of Helldivers 2 is just blowing stuff up—bugs, buildings, and, yes, even teammates. Friendly fire is a core part of the experience, and whether by accident or on purpose, you will inevitably end up turning your munitions on your friends. My bad!

Some controversial balance patches put the game into a bit of an identity crisis for a while, but things seem to be back on track. I’ll admit the game didn’t have the staying power for me that it seemed to for others, but it was undeniably a highlight of the year.

-Aaron Zimmerman

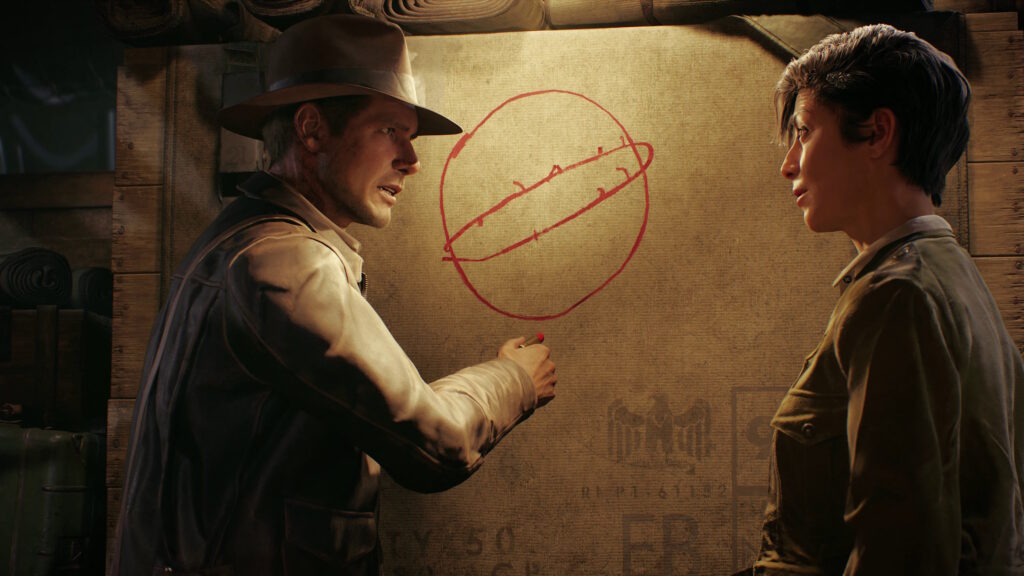

Indiana Jones and the Great Circle

MachineGames; Windows, PS5, Xbox Series X/S

Credit: Bethesda / MachineGames

A new game based on the Indiana Jones license has a lot to live up to, both in terms of the films and TV shows that inspired it and the well-remembered games that preceded it. The Great Circle manages to live up to those expectations, crafting the most enjoyable Indy adventure in years.

The best part of the game is contained in the main storyline, captured mainly in exquisitely madcap cut scenes featuring plenty of the pun-filled, devil-may-care quipiness that Indy is known for. Voice actor Troy Baker does a great job channeling Harrison Ford (by way of Jeff Goldblum) as Indy, while antagonist Emmerich Voss provides all the scenery-chewing Nazi shenanigans you could want from the ridiculous, magical-realist storyline.

The stealth-action gameplay is a little more pedestrian but still manages to distinguish itself with suitably crunchy melee combat and the enjoyable improvisation of attacking Nazis with everyday items, from wrenches to plungers. And while the puzzles and side-quests can feel a bit basic at times, there are enough hidden trinkets in out-of-the-way corners to encourage completionists to explore every inch of the game’s intricately detailed open-world environments.

It’s just the kind of light-hearted, escapist, exploratory fun we need in these troubled times. Welcome back, Indy! We missed you!

-Kyle Orland

The Legend of Zelda: Echoes of Wisdom

Nintendo; Switch

After decades and decades of Zelda games where you don’t actually play as Zelda, there was a lot of pressure on a game where you finally get to control the princess herself as the protagonist (those CD-i monstrosities from the ’90s are best forgotten). Fortunately, Zelda’s turn in full control of her own series captures the franchise’s old-school, light-hearted adventuring fun with a few modern twists.

The main draw here is the titular “echo” abilities, which let Zelda copy enemies and objects that can be summoned in multiple copies with a special wand. This eventually opens up to allow for a number of inventive ways to solve some intricate puzzles in what feels like a heavily simplified version of Tears of the Kingdom‘s more complex crafting tools.

My favorite bit in Echoes of Wisdom, though, might be summoning copies of defeated enemies to fight new enemies in a kind of battle royale. As much as I love Link’s sword-swinging antics (which are partially captured here), just watching these magical minions do my combat for me is more than half of the fun in Echoes of Wisdom.

Even without those twists, though, Echoes of Wisdom provides all the old-school 2D Zelda dungeon exploring you could hope for, and the lighthearted storyline to match. Here’s hoping this isn’t the last time we’ll see Zelda taking a starring role in her own legends.

-Kyle Orland

Llamasoft: The Jeff Minter Story

Digital Eclipse; Windows, PS4/5, Xbox One/Series, Switch

I went into this latest Digital Eclipse playable museum as someone who had only a passing familiarity with Jeff Minter. I knew him mainly as a revered game development elder with a penchant for psychedelic graphics and an association with Tempest 2000. Then I spent hours devouring The Jeff Minter Story on my Steam Deck during a long flight, soaking in the full history of a truly unique character in the annals of gaming history.

The emulated games on this collection are actually pretty hit or miss, from a modern game design perspective. But the collection of interviews and supporting material on offer here are top-notch, putting each game into the context of the time and of Minter’s personal journey through an industry that was still in its infancy. I especially liked the scanned versions of Minter’s newsletter, sent to his early fans, which included plenty of diatribes and petty dramas about his game design peers and the industry as a whole.

There are few other figures in the early history of games that would merit this kind of singular focus—even early games were too often the collaborative product of larger companies with a more corporate focus (as seen in Digital Eclipse’s previous Atari 50. But I reveled in this opportunity to get to know Minter better for his unique and quixotic role in early gaming history.

-Kyle Orland

Lorelei and the Laser Eyes

Simogo; Windows, PS4/5, Switch

You’d be forgiven for finding Lorelei and the Laser Eyes at least a little pretentious. Everything from the black-and-white presentation—laced with only the occasional flash of red for emphasis —to the Twin Peaks-style absurdist writing to the grand pronouncements on the Importance and Beauty of Art make for a game that feels like it’s trying a little too hard, at points.

Push past that surface, though, and you’ll find one of the most intricately designed interactive puzzle boxes ever committed to bits and bytes. Lorelei goes well beyond the simple tile-pushing and lock-picking tasks that are laughably called “puzzles” in most other adventure games. The mind-teasers here require real out-of-the-box thinking, careful observation of the smallest environmental details, and multi-step deciphering of arcane codes.

This is a game that’s not afraid to cut you off from massive chunks of its content if you’re not able to get past a single near-inscrutable locked door puzzle—don’t feel bad if you need to consult a walkthrough at some point to move on. It’s also a game that practically requires a pen and paper notes to keep track of all the moving pieces—your notebook will look like the scribblings of a madman by the time you’re done.

And you may actually feel a little mad as you try to unravel the meaning of the game’s multiple labyrinthine layers and self-aware, time-bending, magical-realist storyline. When it all comes together at the end, you may just find yourself surprisingly moved not just by the intricate design, but by that oft-pretentious plot as well.

-Kyle Orland

Metal Slug Tactics

Leikir Studio; Windows, PS4/5, Xbox One/Series, Switch

Credit: Dotemu

Good tactics games are all about how the game plays in your mind. How many ways can you overcome this obstacle, maximize this turn, and synergize your squad’s abilities? So it’s a very nice bonus when such a well-made pile of engaging decisions also happens to look absolutely wonderful and capture the incredibly detailed sense of motion of a legendary run-and-gun franchise.

That’s Metal Slug Tactics, and it’s one of the most surprising successes of 2024. It delivers the look and feel of a franchise that isn’t easy to get right, and it translates those games’ feeling of continuous motion into turn-based tactics. The more you move, shoot, and team up each turn, the better you’ll do. You can do a level or two on a subway ride, crank out a rogue-ish run on a lunch break, and keep getting rewarded with new characters, unlocks, and skill tree branches.

If you’re always contemplating a replay of Final Fantasy Tactics, but might like a new challenge, consider giving this unlikely combination of goofy arcade revival and deep strategy a go.

-Kevin Purdy

Parking Garage Rally Circuit

Walaber Entertainment; Windows

The rise of popular, ultra-detailed racing sims like Gran Turismo and Forza Motorsport has coincided with a general decline in the drift-heavy, arcadey side of the genre. Titles like Ridge Racer Sega Rally or even Crazy Taxi now belong more in the industry’s nostalgic memories than its present top-sellers.

Parking Garage Rally Circuit is doing its best to bring the arcade racer genre back single-handedly. The game’s perfectly tuned drifting controls make every turn a joyful sliding experience, complete with chainable post-drift boosts for those who want to tune that perfect speedy line. It captures that great feeling of being just on the edge of losing control, while still holding onto the edge of that perfect drift.

It all takes place, as the name implies, winding up, down, over, and through some well-designed parking garages. Each track’s short laps (which take a minute or less) ensure you can practically memorize the best paths after just a little bit of play. But the stopped cars and large traffic dividers provide for some hilarious physics-based crashes when your racing line does go wrong.

The game earns extra nostalgia points for a variety of visual effects and graphics options that accurately mimic Dreamcast-era consoles and/or emulation-era PC hardware. But the game’s extensive online leaderboards and ghost-racers help it feel like a decidedly modern take on a classic genre.

-Kyle Orland

Pepper Grinder

Ahr Ech; Windows, MacOS, Linux, PS4/5, Xbox One/Series, Switch

It’s amazing how far a platform game can get on nothing more than a novel control scheme. Pepper Grinder is a case in point here, based around a tiny, blue-haired protagonist who uses an oversized drill to tunnel through soft ground like some kind of human-machine-snake hybrid.

Navigating through the dirt in large, undulating curves is fun enough, but the game really shines when Pepper bursts out through the top layer of dirt in large, arcing jumps. Chaining these together, from dirt clump to dirt clump, is the most instantly compelling new 2D navigation scheme we’ve seen in years and creates some beautiful, almost balletic curves through the levels once you’ve mastered it.

The biggest problem with Pepper Grinder is that the game is over practically before it really gets going. And while some compelling time-attack and item-collection challenges help to extend the experience a bit, we really hope some new DLC or a proper sequel is coming soon to give us a new excuse to wind our way through the dirt.

-Kyle Orland

The Rise of the Golden Idol

Color Gray Games; Windows, MacOS, iOS, Android, PS4/5, Xbox One/Series, Switch

In 2022, The Case of the Golden Idol proved that details like a controllable protagonist or elaborate cut scenes are unnecessary for a good murder mystery-solving puzzle adventure. All you need is a series of lightly animated vignettes, a way to uncover the smallest hidden details in those vignettes, and a fill-in-the-blanks interface to let you piece together the disparate clues.

As a follow-up, Rise moves the 18th-century setting of the original into the 20th century, bringing the mysterious, powerful idol to the attention of both academic scientists and mass media executives who seek to exploit its mind-altering powers. From your semi-omniscient perspective, you have to figure out not just the names and motivations of those pulled into the idol’s orbit, but the somewhat inscrutable powers of the idol itself.

Rise adds a few interesting new twists, like the ability to scrub through occasional video animations for visual clues and the ability to track certain scenes throughout multiple times of day. At its core, though, this is an extension of the best-in-class, pure deductive reasoning gameplay we saw in the original game, with a slightly more modern twist. This is yet another 2024 favorite that requires strong attention to detail and logical inference from very small hints.

It all comes together in a satisfying conclusion that leaves the door wide open for a sequel that we can’t wait for.

-Kyle Orland

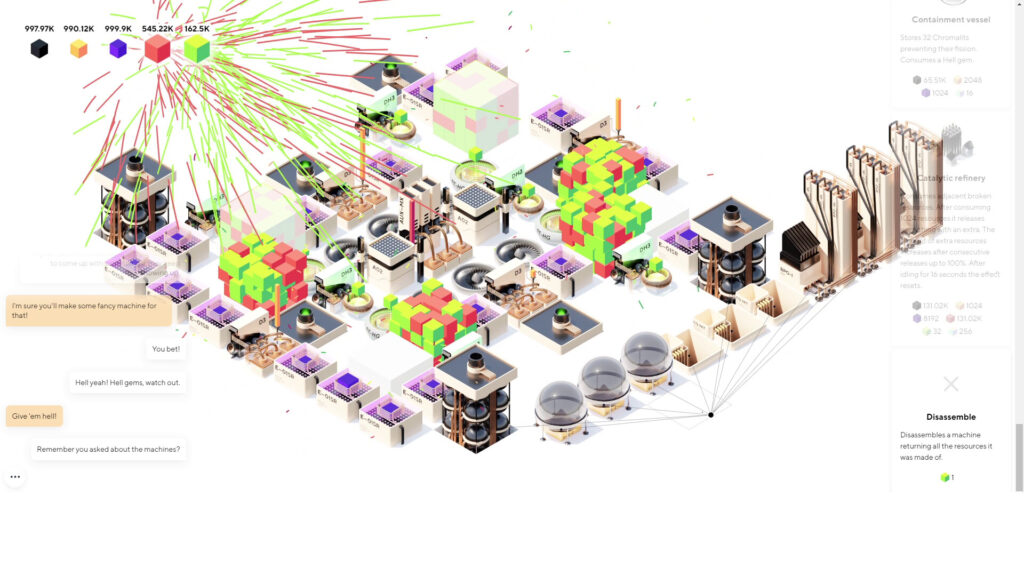

Satisfactory

Coffee Stain Studios; Windows

Danish publisher Coffee Stain makes gaming success seem so simple. Put a game with a goofy feel, a corporate dystopia, and complex systems into early access. Iterate, cultivate feedback and a sense of ownership with the community. Take your time, refine, and then release the game, without any revenue-grabbing transactions or add-ons, beyond fun cosmetics. They did it with Deep Rock Galactic, and they’ve done it again with Satisfactory. By the time the game hit 1.0, the only thing left to add was “Premium plumbing.”

It’s remarkably fun to live on the bad-guy side of The Lorax, exploiting a planet’s natural resources to create a giant factory system producing widgets for corporate wellbeing. The first-person perspective might seem odd for game with such complex systems, but it heightens your sense of accomplishment. You didn’t just choose to put a conveyor belt between that ore extractor and that fabricator; you personally staked out that deposit, and your ran the track yourself.

The systems are incredibly deep, but it can be quite relaxing to wander around your planet-sized industrial park, thinking up ways that things might run better, faster, with no interruptions. It’s the kind of second job you’re happy to buy into, giving you a deep sense of accomplishment for learning the ins and outs of this system, even as it gently mocks you for engaging with it. Satisfactory has itself worked for years to refine the most efficient gameplay for its bravest fans, and now it’s ready to employ the rest of us.

-Kevin Purdy

Sixty Four

Oleg Danilov; Windows, Mac

I try not to think about, or write about, games in the manner of “dollars to enjoyment ratio.” Games often get cheaper over time, everybody enjoys them differently, and they’re art, too, as well as commerce. But, folks, come on: $6 for Sixty Four? If you play it for one hour and just smile a few times at its oddities and tiny cubes, that was less than a big-city latte or beer.

But you will almost certainly play Sixty Four for more than one hour, and maybe many more hours than that if you enjoy games with systems, building, and resources. You build and place machines to extract resources, use those resources to fund new and better machines, rearrange your machines, and eventually create beautiful workflows that are largely automated. Why do you do this? It’s a fun, dark mystery.

The game looks wonderful in its SimCity 2000/3000-esque style. It can be mentally taxing, but you can’t really lose; you can even leave the game window open in the background while you convince your boss or remote work software that you’re otherwise productive. It’s a fever dream I’d recommend to most anybody, unless they dread a repeat of the many lost days to games like Factorio, Satisfactory, or even Universal Paperclips. Just wishlist it, in that case; what could go wrong?

-Kevin Purdy

Tactical Breach Wizards

Suspicious Developments; Windows

Credit: Suspicious Developments

What can you do to spice up turn-based tactics, a rather mature genre?

Tactical Breach Wizards adds future-seeing, time-bending, hex-placing wizards, for one thing. It refines the heck out of grid combat, for another, adding window-tossing and door-sealing into the mix, and giving enemies a much wider array of attacks than area-of-effect variations. Finally, it wraps this all up in an inventive sci-fi narrative, one with an engaging plot, characters that reveal themselves one quip at a time, and an overall sense of wonderment at a charming, bizarre world of militarized magic.

In other words, you could put some joy into your turn-based combat, while still offering intricate challenges and clever levels.

Tom Francis’ unique sense of humor, seen previously in Gunpoint and Heat Signature, is given space here to shine, and it’s a wonderful wrapper for all the missions and upgrade decisions. It’s pretty ridiculous to be a wizard, wielding a laser-scoped rifle that fires crystal energy, plotting how to hit three guards at once with your next blast. Tactical Breach Wizards knows this, jokes about it, and then celebrates with you when you pull it off. It’s both a hoot, and a very good shoot.

-Kevin Purdy

UFO 50

Mossmouth; Windows

In recent years, modern games have started evoking the blocky polygons and smeary textures of early 3D games to appeal to nostalgic 20- and 30-somethings. UFO 50 has its nostalgic foot placed firmly in an earlier generation of ’80s and ’90s console gaming, with a bit of early ’00s Flash game design thrown in for good measure.

Flipping your way through the extremely wide variety of games on offer here is like an eminently enjoyable trip through random titles in an emulator’s (legally obtained) classic ROMs folder—just set in an alternate universe. There are plenty of shmups and platform games befitting the ostensible gaming era being recreated—but you also get full-fledged strategy, puzzle, arcade, racing, adventure, and RPG titles, on top of a few so unique that I can’t find any real historical genre analog for. These well-designed titles evoke the classics—everything from Bad Dudes and Bubble Bobble to Super Dodge Ball and Smash TV—without ever feeling like a simple rehash of games you remember from your youth.

While there’s the usual spread of quality you’d expect from such a wide-ranging collection, even the worst-made title in UFO 50 shows a level of care and attention to detail that will delight anyone with even a passing interest in game design and/or history. Not every game in UFO 50 will be one of your all-time favorites, but I’d be willing to wager that any gamer of a certain age will find quite a few that will eat away plenty of pleasant, nostalgic hours.

-Kyle Orland

Kyle Orland has been the Senior Gaming Editor at Ars Technica since 2012, writing primarily about the business, tech, and culture behind video games. He has journalism and computer science degrees from University of Maryland. He once wrote a whole book about Minesweeper.

Ars Technica’s top 20 video games of 2024 Read More »