How old is the earliest trace of life on Earth?

A recent conference sees doubts raised about the age of the oldest signs of life.

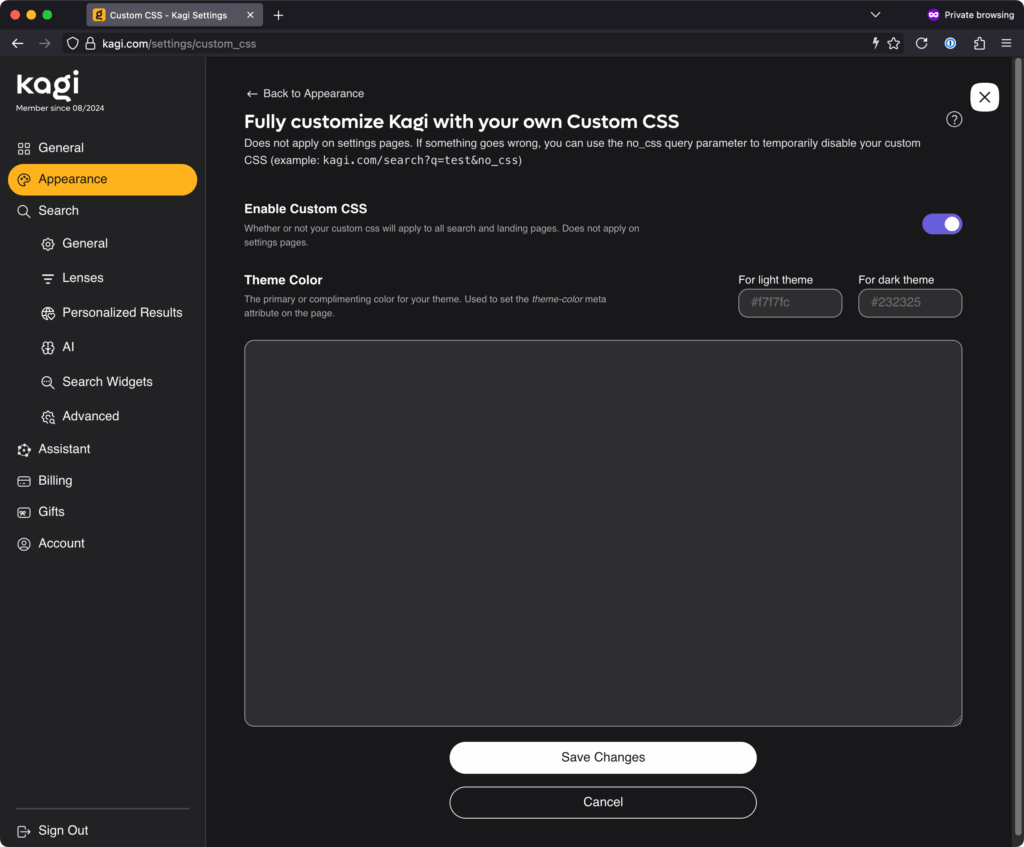

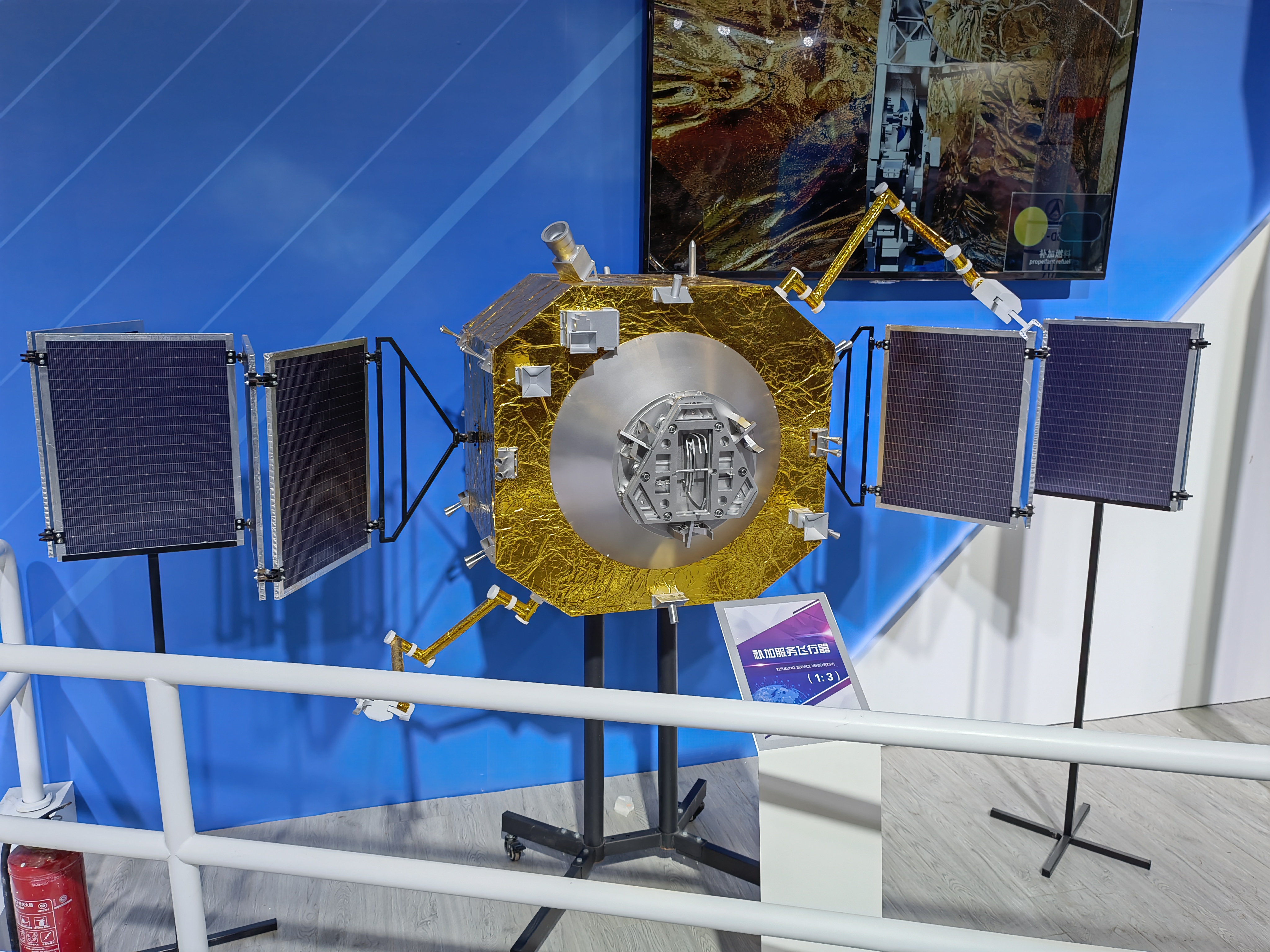

Where the microbe bodies are buried: metamorphosed sediments in Labrador, Canada containing microscopic traces of carbon. Credit: Martin Whitehouse

The question of when life began on Earth is as old as human culture.

“It’s one of these fundamental human questions: When did life appear on Earth?” said Professor Martin Whitehouse of the Swedish Museum of Natural History.

So when some apparently biological carbon was dated to at least 3.95 billion years ago—making it the oldest remains of life on Earth—the claim sparked interest and skepticism in equal measure, as Ars Technica reported in 2017.

Whitehouse was among those skeptics. This July, he presented new evidence to the Goldschmidt Conference in Prague that the carbon in question is only between 2.7–2.8 billion years old, making it younger than other traces of life found elsewhere.

Organic carbon?

The carbon in question is in rock in Labrador, Canada. The rock was originally silt on the seafloor that, it’s argued, hosted early microbial life that was buried by more silt, leaving the carbon as their remains. The pressure and heat of deep burial and tectonic events over eons have transformed the silt into a hard metamorphic rock, and the microbial carbon in it has metamorphosed into graphite.

“They are very tiny, little graphite bits,” said Whitehouse.

The key to showing that this graphite was originally biological versus geological is its carbon isotope ratio. From life’s earliest days, its enzymes have preferred the slightly lighter isotope carbon-12 over the marginally heavier carbon-13. Organic carbon is therefore much richer in carbon-12 than geological carbon, and the Labrador graphite does indeed have this “light” biological isotope signature.

The key question, however, is its true age.

Mixed-up, muddled-up, shook-up rocks

Sorting out the age of the carbon-containing Labrador rock is a geological can of worms.

These are some of the oldest rocks on the planet—they’ve been heated, squished, melted, and faulted multiple times as Earth went through the growth, collision, and breakup of continents before being worn down by ice and exposed today.

“That rock itself is unbelievably complicated,” said Whitehouse. “It’s been through multiple phases of deformation.”

In general, the only ways to date sediments are if there’s a layer of volcanic ash in them, or by distinctive fossils in the sediments. Neither is available in these Labrador rocks.

“The rock itself is not directly dateable,” said Whitehouse, “so then you fall onto the next best thing, which is you want to look for a classic field geology cross-cutting relationship of something that is younger and something that you can date.”

The idea, which is as old as the science of geology itself, is to bracket the age of the sediment by finding a rock formation that cuts across it. Logically, the cross-cutting rock is younger than the sediment it cuts across.

In this case, the carbon-containing metamorphosed siltstone is surrounded by swirly, gray banded gneiss rock, but the boundary between the siltstone and the gray gneiss is parallel, so there’s no cross-cutting to use.

Professor Tsuyoshi Komiya of The University of Tokyo was a coauthor on the 3.95 billion-year age paper. His team used a cross-cutting rock they found at a different location and extrapolated that to the carbon-bearing siltstone to constrain its age. “It was discovered that the gneiss was intruded into supracrustal rocks (mafic and sedimentary rocks),” said Komiya in an email to Ars Technica.

But Whitehouse disputes that inference between the different outcrops.

“You’re reliant upon making these very long-distance assumptions and correlations to try to date something that might actually not have anything to do with what you think you’re dating,” he said.

Professor Jonathan O’Neil of the University of Ottawa, who was not involved in either Whitehouse’s or Komiya’s studies but who has visited the outcrops in question, agrees with Whitehouse. “I remember I was not convinced either by these cross-cutting relationships,” he told Ars. “It’s not clear to me that one is necessarily older than the other.”

With the field geology evidence disputed, the other pillar holding up the 3.95-billion-year-old date is its radiometric date, measured in zircon crystals extracted from the rocks surrounding the metamorphosed siltstone.

The zircon keeps the score

Geologists use the mineral zircon to date rocks because when it crystallizes, it incorporates uranium but not lead. So as radioactive uranium slowly decays into lead, the ratio of uranium to lead provides the age of the crystal.

But the trouble with any date obtained from rocks as complicated as these is knowing exactly what geological event it dates—the number alone means little without the context of all the other geological evidence for the events that affected the area.

Both Whitehouse and O’Neil have independently sampled and dated the same rocks as Komiya’s team, and where Komiya’s team got a date of 3.95, Whitehouse’s and O’Neil’s new dates are both around 3.87 billion years. Importantly, O’Neil’s and Whitehouse’s dates are far more precise, with errors around plus-or-minus 5 or 6 million years, which is remarkably precise for dates in rocks this old. The 3.95 date had an error around 10 times bigger. “It’s a large error,” said O’Neil.

But there’s a more important question: How is that date related to the age of the organic carbon? The rocks have been through many events that could each have “set” the dates in the zircons. That’s because zircons can survive multiple re-heatings and even partial remelting, with each new event adding a new layer, or “zone,” on the outer surface of the crystal, recording the age of that event.

“This rock has seen all the events, and the zircon in it has responded to all of these events in a way that, when you go in with a very small-scale ion beam to do the sampling on these different zones, you can pick apart the geological history,” Whitehouse said.

Whitehouse’s team zapped tiny spots on the zircons with a beam of negatively charged oxygen ions to dislodge ions from the crystals, then sucked away these ions into a mass spectrometer to measure the uranium-lead ratio, and thus the dates. The tiny beam and relatively small error have allowed Whitehouse to document the events that these rocks have been through.

“Having our own zircon means we’ve been able to go in and look in more detail at the internal structure in the zircon,” said Whitehouse. “Where we might have a core that’s 3.87, we’ll have a rim that is 2.7 billion years, and that rim, morphologically, looks like an igneous zircon,” said Whitehouse.

That igneous outer rim of Whitehouse’s zircons shows that it formed in partially molten rock that would have flowed at that time. That flow was probably what brought it next to the carbon-containing sediments. Its date of 2.7 billion years ago means the carbon in the sediments could be any age older than that.

That’s a key difference from Komiya’s work. He argues that the older dates in the cores of the zircons are the true age of the cross-cutting rock. “Even the igneous zircons must have been affected by the tectonothermal event; therefore, the obtained age is the minimum age, and the true age is older,” said Komiya. “The fact that young zircons were found does not negate our research.”

But Whitehouse contends that the old cores of the zircons instead record a time when the original rock formed, long before it became a gneiss and flowed next to the carbon-bearing sediments.

Zombie crystals

Zircon’s resilience means it can survive being eroded from the rock where it formed and then deposited in a new, sedimentary rock as the undead remnants of an older, now-vanished landscape.

The carbon-containing siltstone contains zombie zircons, and Whitehouse presented new data on them to the Goldschmidt Conference, dating them to 2.8 billion years ago. Whitehouse argues that these crystals formed in an igneous rock 2.8 billion years ago and then were eroded, washed into the sea, and settled in the silt. So the siltstone must be no older than 2.8 billion years old, he said.

“You cannot deposit a zircon that is not formed yet,” O’Neil explained.

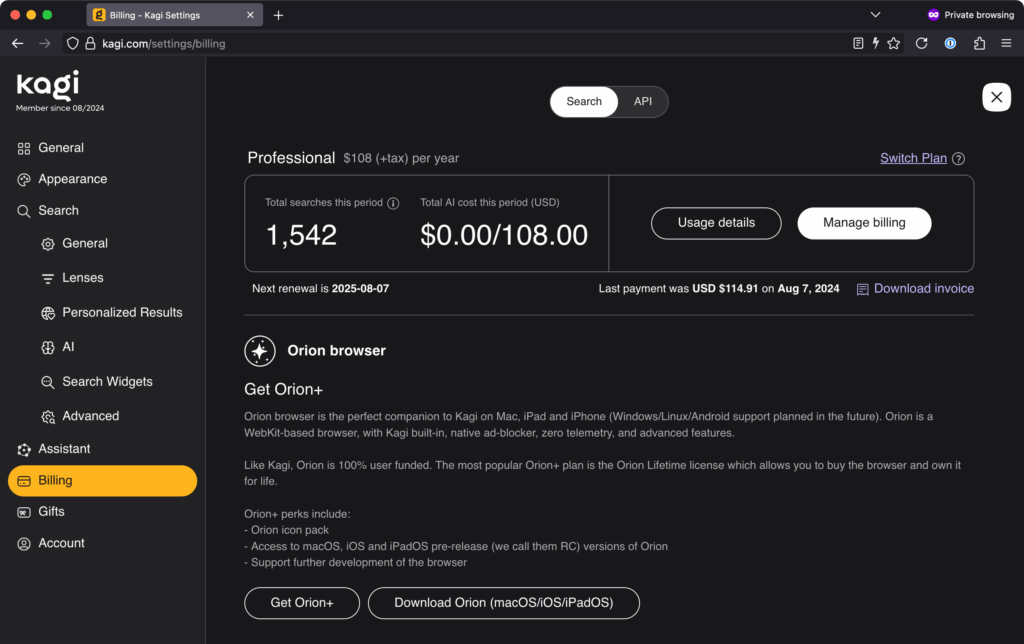

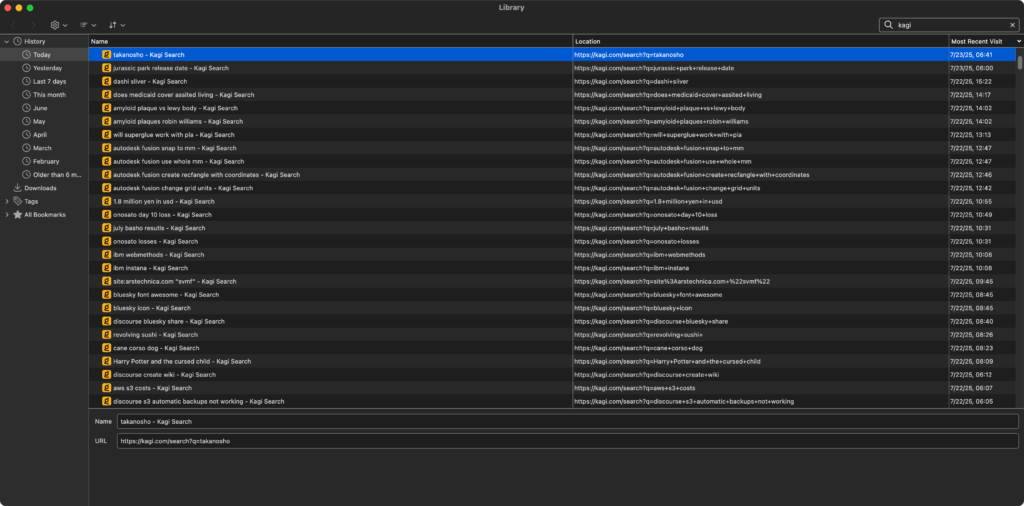

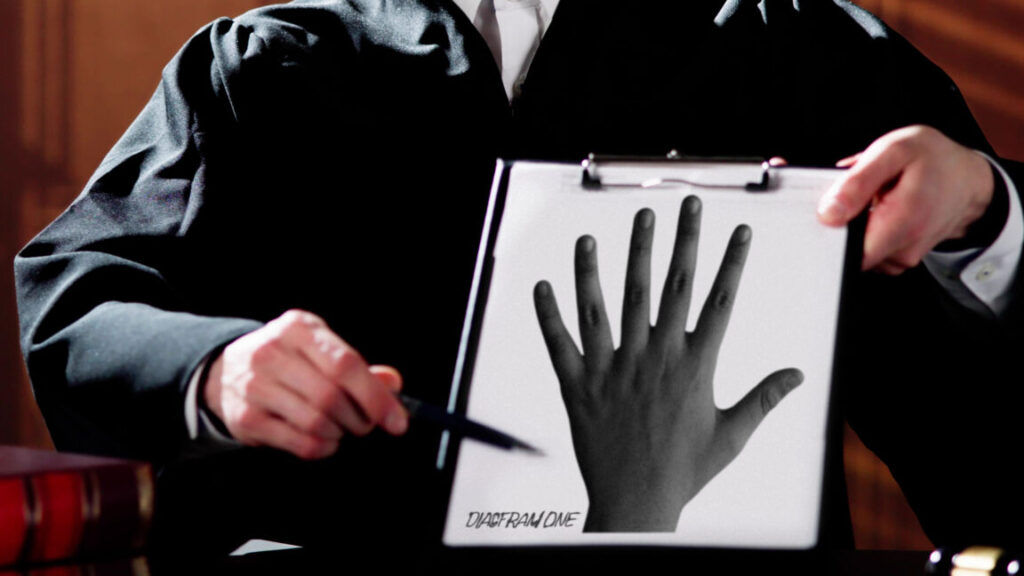

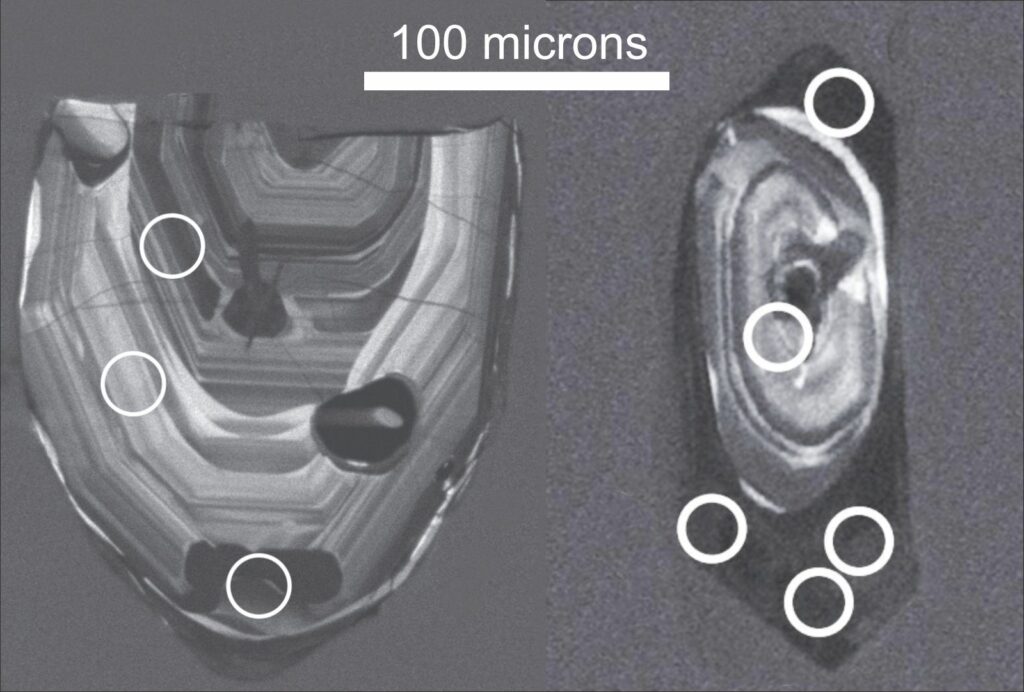

Tiny recorders of history – ancient zircon crystals from Labrador. Left shows layers built up as the zircon went through many heating events. Right shows a zircon with a prism-like outer shape showing that it formed in igneous conditions around an earlier zircon. Circles indicate where an ion beam was used to measure dates. Credit: Martin Whitehouse

This 2.8-billion-year age, along with the igneous zircon age of 2.7 billion years, brackets the age of the organic carbon to anywhere between 2.8 and 2.7 billion years old. That’s much younger than Komiya’s date of 3.95 billion years old.

Komiya disagrees: “I think that the estimated age is minimum age because zircons suffered from many thermal events, so that they were rejuvenated,” he said. In other words, the 2.8-billion-year age again reflects later heating, and the true date is given by the oldest-dated zircons in the siltstone.

But Whitehouse presented a third line of evidence to dispute the 3.95-billion-year date: isotopes of hafnium in the same zombie zircon crystals.

The technique relies on radioactive decay of lutetium-176 to hafnium-176. If the 2.8-billion-year age resulted from rejuvenation by later heating, it would have had to have formed from material with a hafnium isotope ratio incompatible with the isotope composition of the early Earth.

“They go to impossible numbers,” said Whitehouse.

The only way that the uranium-lead ratio can be compatible with the hafnium in the zircons, Whitehouse argued, is if the zircons that settled in the silt had crystallized around 2.8 billion years ago, constraining the organic carbon to being no older than that.

The new oldest remains of life on Earth, for now

If the Labrador carbon is no longer the oldest trace of life on Earth, then where are the oldest remains of life now?

For Whitehouse, it’s in the 3.77-billion-year-old Isua Greenstone Belt in Greenland: “I’m willing to believe that’s a well-documented age… that’s what I think is the best evidence for the oldest biogenicity that we have,” said Whitehouse.

O’Neil recently co-authored a paper on Earth’s oldest surviving crustal rocks, located next to Hudson Bay in Canada. He points there. “I would say it’s in the Nuvvuagittuq Greenstone belt,” said O’Neil, “because I would argue that these rocks are 4.3 billion years old. Again, not everybody agrees!” Intriguingly, the rocks he is referring to contain carbon with a possibly biological origin and are thought to be the remains of the kind of undersea vent where life could well have first emerged.

But the bigger picture is the fact that we have credible traces of life of this vintage—be it 3.8 or 3.9 or 4.3 billion years.

Any of those dates is remarkably early in the planet’s 4.6-billion-year life. It’s long before there was an oxygenated atmosphere, before continents emerged above sea level, and before plate tectonics got going. It’s also much older than the oldest microbial “stromatolite” fossils, which have been dated to about 3.48 billion years ago.

O’Neil thinks that once conditions on Earth were habitable, life would have emerged relatively fast: “To me, it’s not shocking, because the conditions were the same,” he said. “The Earth has the luxury of time… but biology is very quick. So if all the conditions were there by 4.3 billion years old, why would biology wait 500 million years to start?”

How old is the earliest trace of life on Earth? Read More »