A Valentine’s Day homage to Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon

That thief turns out to be Jen, who has secretly been studying martial arts. And Jen’s really not keen on her upcoming arranged marriage because she has fallen in love with a bandit named Lo “Dark Cloud” Xiao Hou (Chang Chen). They are the symbolic tiger and dragon, with Lo as the unchanging yin (tiger) and Jen as the dynamic yang (the hidden dragon).

(WARNING: Major spoilers below. Stop reading now if you haven’t seen the entire film.)

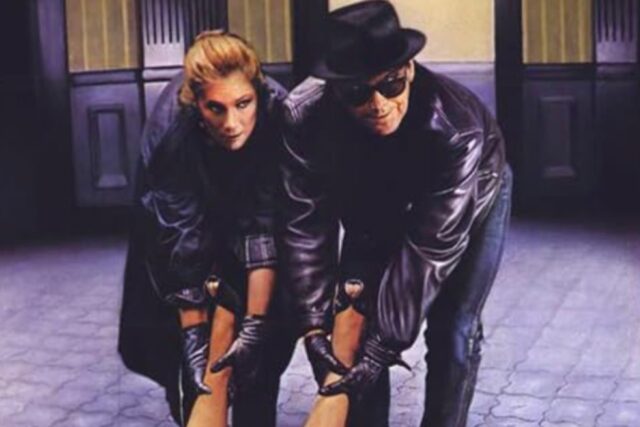

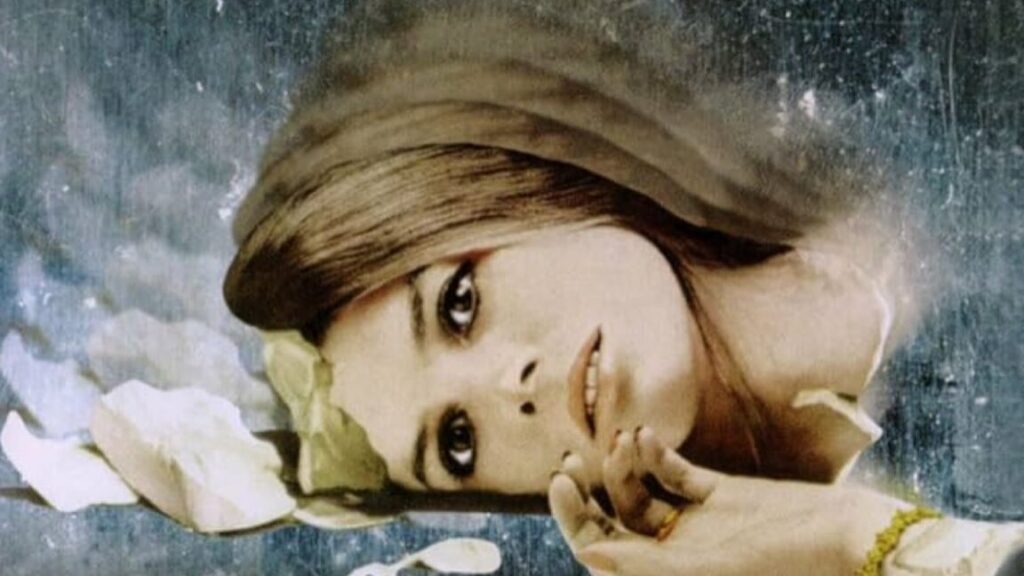

Longtime friends Mu Bai (Chow Yan-Fat) and Shu Lien (Michelle Yeoh) have refrained from declaring their love out of respect for Shu Lien’s late fiancé. Sony Pictures Classics

There are multiple clashes between our main characters, most notably Jen battling Shu Lien, and a famous sequence where Mu Bai pursues Jen across the treetops of a bamboo forest, deftly balancing on the swaying branches and easily evading Jen’s increasingly undisciplined sword thrusts. It’s truly impressive wire work (all the actors performed their own stunts), in fine wuxia tradition. Jen is gifted, but arrogant and defiant, refusing Mu Bai’s offer of mentorship; she thinks with Green Destiny she will be invincible and has nothing more to learn. Ah, the arrogance of youth.

Eventually, Jen is betrayed by her former teacher, Jade Fox, who is bitter because Jen has surpassed her skills—mostly because Jade Fox is illiterate and had to rely on a stolen manual’s diagrams, while the literate Jen could read the text yet did not share those insights with her teacher. Jade Fox is keeping her drugged in a cave, intending to poison her, when Mu Bai and Shu Lien come to the rescue. In the ensuing battle, Mu Bai is struck by one of Jade Fox’s poison darts. Jen rushes off to bring back the antidote, but arrives too late. Mu Bai dies in Shu Lien’s arms, as the two finally confess how much they love each other.

(sniff) Sorry, something in my eye. Anyway, the ever-gracious Shu Lien forgives the young woman and tells her to be true to herself, and to join Lo on Mount Wudang. But things don’t end well for our young lovers either. After spending the night together, Lo finds Jen standing on a bridge at the edge of the mountain. Legend has it that a man once made a wish and jumped off the mountain. His heart was pure so his wish was granted and he flew away unharmed, never to be seen again. Jen asks Lo to make a wish before swan-diving into the mist-filled chasm. Was her heart pure? Did Lo get his wish for them to back in the desert, happily living as renegades? Or did she plunge to her death? We will never know. Jen is now part of the legend.

A Valentine’s Day homage to Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon Read More »