Google announces Gemini 3.1 Pro, says it’s better at complex problem-solving

Another day, another Google AI model. Google has really been pumping out new AI tools lately, having just released Gemini 3 in November. Today, it’s bumping the flagship model to version 3.1. The new Gemini 3.1 Pro is rolling out (in preview) for developers and consumers today with the promise of better problem-solving and reasoning capabilities.

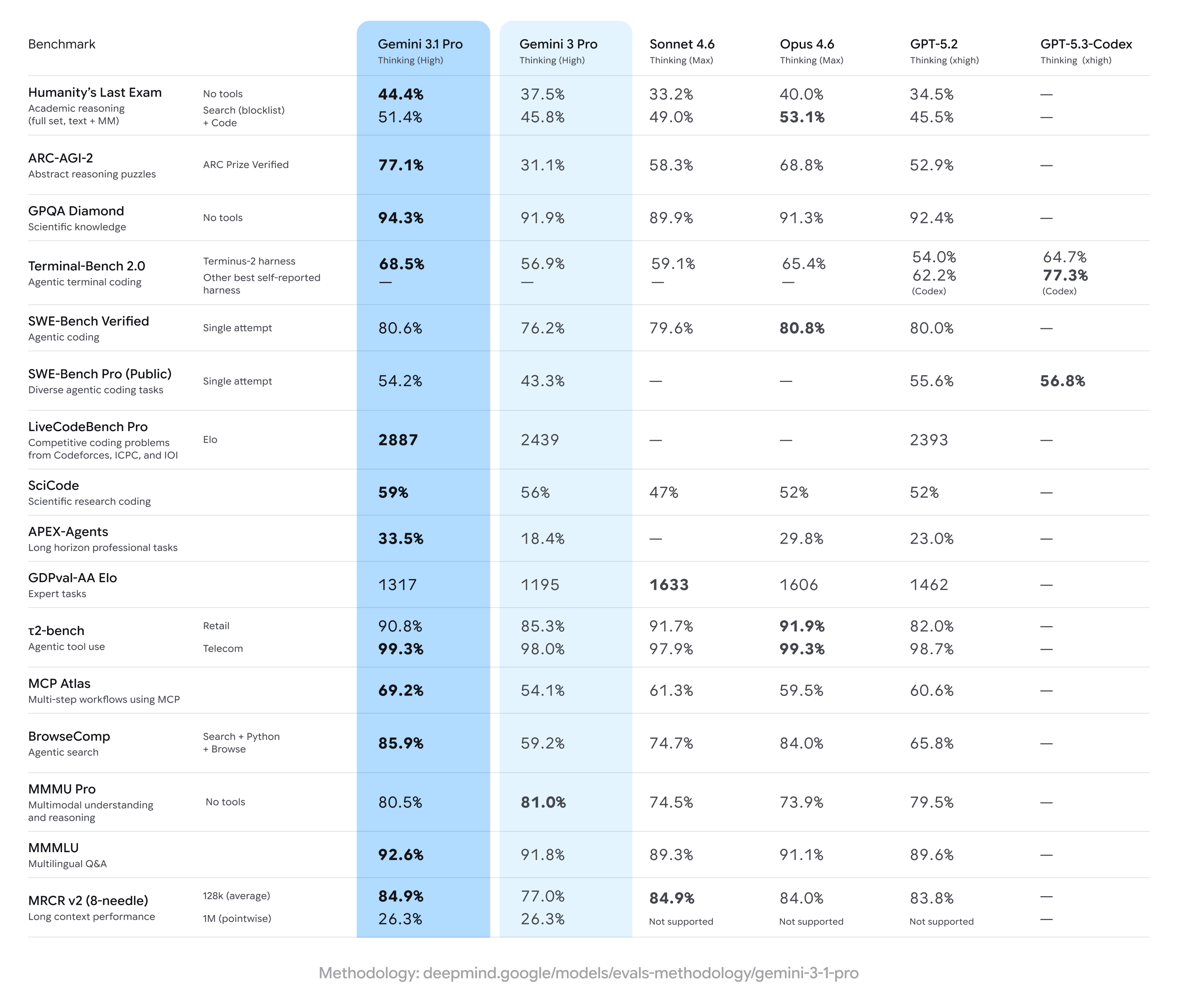

Google announced improvements to its Deep Think tool last week, and apparently, the “core intelligence” behind that update was Gemini 3.1 Pro. As usual, Google’s latest model announcement comes with a plethora of benchmarks that show mostly modest improvements. In the popular Humanity’s Last Exam, which tests advanced domain-specific knowledge, Gemini 3.1 Pro scored a record 44.4 percent. Gemini 3 Pro managed 37.5 percent, while OpenAI’s GPT 5.2 got 34.5 percent.

Credit: Google

Google also calls out the model’s improvement in ARC-AGI-2, which features novel logic problems that can’t be directly trained into an AI. Gemini 3 was a bit behind on this evaluation, reaching a mere 31.1 percent versus scores in the 50s and 60s for competing models. Gemini 3.1 Pro more than doubles Google’s score, reaching a lofty 77.1 percent.

Google has often gloated when it releases new models that they’ve already hit the top of the Arena leaderboard (formerly LM Arena), but that’s not the case this time. For text, Claude Opus 4.6 edges out the new Gemini by four points at 1504. For code, Opus 4.6, Opus 4.5, and GPT 5.2 High all run ahead of Gemini 3.1 Pro by a bit more. It’s worth noting, however, that the Arena leaderboard is run on vibes. Users vote on the outputs they like best, which can reward outputs that look correct regardless of whether they are.

Google announces Gemini 3.1 Pro, says it’s better at complex problem-solving Read More »