Bringing the “functionally extinct” American chestnut back from the dead

Wiped out in its native range by invasive pathogens, the trees may make a comeback.

Very few people alive today have seen the Appalachian forests as they existed a century ago. Even as state and national parks preserved ever more of the ecosystem, fungal pathogens from Asia nearly wiped out one of the dominant species of these forests, the American chestnut, killing an estimated 3 billion trees. While new saplings continue to sprout from the stumps of the former trees, the fungus persists, killing them before they can seed a new generation.

But thanks in part to trees planted in areas where the two fungi don’t grow well, the American chestnut isn’t extinct. And efforts to revive it in its native range have continued, despite the long generation times needed to breed resistant trees. In Thursday’s issue of Science, researchers describe their efforts to apply modern genomic techniques and exhaustive testing to identify the best route to restoring chestnuts to their native range.

Multiple paths to restoration

While the American chestnut is functionally extinct—it’s no longer a participant in the ecosystems it once dominated—it’s most certainly not extinct. Two Asian fungi that have killed it off in its native range; one causes chestnut blight, while a less common pathogen causes a root rot disease. Both prefer warmer, humid environments and persist there because they can grow asymptomatically on distantly related trees, such as oaks. Still, chestnuts planted outside the species’ original range—primarily in drier areas of western North America—have continued to thrive.

There is also a virus that attacks the chestnut blight fungus, allowing a few trees to survive in areas where that virus is common. Finally, a handful of trees have grown to maturity in the American chestnut’s original range. These trees, which the paper refers to as LSACs (large surviving American chestnuts), suggest that there might have been some low level of natural resistance within the now-vanished population.

Those trees are central to one of the efforts to restore the American chestnut. If enough of them have distinct means of resisting the fungi, interbreeding them might produce a strain that not only survives the fungi but can also thrive in the Appalachians.

A related approach took advantage of the fact that the American chestnut can produce fertile hybrids with the Chinese chestnut, which had co-evolved with the introduced fungi and were thus resistant to lethal infections. The hope was that continued back-breeding of these hybrids with American chestnuts would result in trees that were very similar to American chestnuts yet retained the fungal resistance of their Asian cousins.

Both efforts suffered from the same problem that faces any biologist working on trees: They are slow-growing and can take years to reach a size at which they produce seeds. The situation was further complicated by the fact that the American chestnut can’t pollinate itself, so you need at least two trees before any breeding is possible.

Concerned about what this might mean for the potential reintroduction of the chestnut into the Appalachians, a third project turned to biotechnology. Research had identified oxalic acid as a key factor in the blight’s virulence. Wheat naturally produces an enzyme that degrades oxalic acid, and researchers inserted the gene that encodes that enzyme into the American chestnut genome, creating a genetically modified tree that can potentially disarm the fungus’ attack.

Without understanding the nature of resistance or the effectiveness of the transgenic gene, there’s no way to know which method would be most effective. So researchers from the American Chestnut Foundation assembled a massive collaboration to examine all these options and determine what would be needed to reintroduce blight-resistant chestnuts into the wild.

Tracking resistance

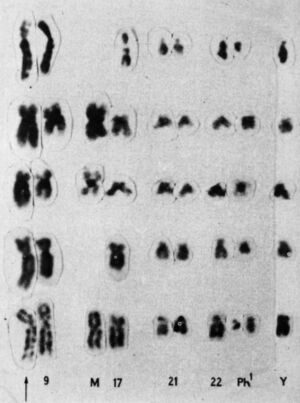

The scale of the effort is immense. All told, the team infected over 4,000 individual trees with the blight fungus and tracked their growth in Appalachian nurseries for an average of over 14 years. The trees were scored for resistance on a zero-to-100 scale based on the damage caused by the infection. This data was combined with some serious lab work; the team produced the highest-quality chestnut genomes yet (of both American and Chinese species) and gathered biochemical data on how the trees respond to infection.

It quickly became apparent that there were significant differences in the growth rates of some of the resistant trees. When planted at sites where viruses kept the blight in check, the Chinese chestnuts grew more slowly than native trees, while hybrids grew at an intermediate rate. That could make a big difference, as rapid growth may have enabled the chestnut to reach its former dominance of the canopy.

Somewhat surprisingly, this slow growth turned out to be a problem for the genetically modified American chestnuts as well. By chance, the wheat gene ended up being inserted into a gene known to be important for the growth of other plants. It seems to be important in the chestnut as well; plants with two copies of the inserted genes survived at 16 percent of their expected rate, and those with a single copy grew 22 percent slower than unmodified trees.

That said, there was a lot of variability among the genetically modified trees, with 4 percent of the tested trees showing both high blight resistance and growth comparable to that of unmodified American chestnuts. It will be important to determine whether this collection of traits remains consistent in ensuing generations.

In a bit of good news, the progeny from surviving American chestnuts grew like American chestnuts. In less good news, among 143 of these trees, only seven had resistance levels of above 50 on the team’s 100-point scale. It’s possible that interbreeding these trees could further boost resistance, but it also poses the risk of creating a population that’s too inbred to thrive after reintroduction.

Root causes

The research team decided to use their testing to investigate the genetic basis of resistance. There’s a very practical reason for this: If resistance is mediated by just a handful of genes that each have large impacts, it should be possible to continue breeding resistant strains back to regular American chestnuts and selecting for resistance. But if there are many factors with relatively small impacts, it will require directed interbreeding of hybrids to maximize both resistance and DNA originating from the American chestnut.

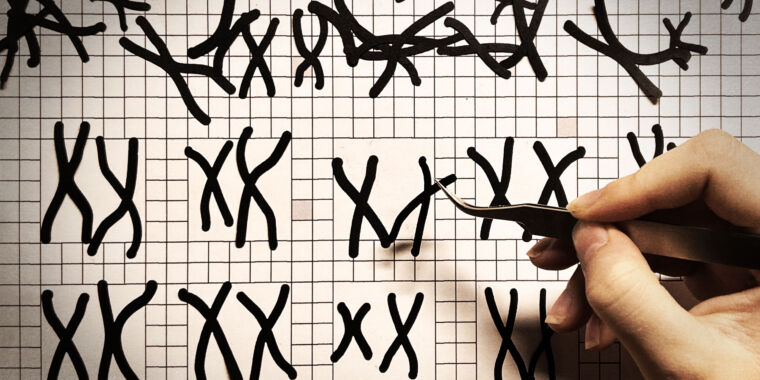

The team completed the highest-quality chestnut genomes for both the American and Chinese species, identifying about 25,000 to 30,000 genes in the different assemblies. They then used this information for two types of genetic analysis: quantitative trait locus identification and genome-wide association. Both approaches aim to identify regions of the genome associated with specific properties and estimate their impact.

The work suggested that resistance arises from a relatively large number of sites, each with relatively minor effects. For example, the sites in the genome identified by quantitative trait analysis typically boosted resistance by about 10 points on the researchers’ 100-point scale. In the genome-wide analysis, 17 individual genetic differences were associated with about a quarter of the heritable resistance traits. All of this suggests that, for the hybrids (and likely for the weaker blight resistance found in surviving American chestnuts), directed breeding among surviving trees will be needed.

For the root rot fungus, in contrast, it looks like there are a limited number of important alleles with a large impact.

The researchers also took an alternative approach to identify resistance factors, comparing 100 chemicals produced by resistant and susceptible strains. Among the 41 chemicals detected at higher levels in the Chinese chestnut, the researchers found a metabolite, lupeol, that completely suppressed the growth of the fungal pathogen. Another, erythrodiol, limited its growth. If we can identify the genes involved in producing those chemicals, we could use that knowledge to guide directed breeding programs—or even engage in gene editing to increase their production.

The team’s current plan is to use genomic predictions to select hybrid seedlings for planting in test orchards, aiming to identify plants with high growth and resistance. From there, the process can be repeated. But even after the exhaustive exploration of resistance traits, the researchers seem to believe that all three approaches—selecting resistant American chestnuts, breeding hybrids derived from Chinese chestnuts, and directed genetic modification—can help bring the American chestnut back.

The researchers warn, though, that as environmental disturbances and invasive species continue to push some key species to the brink of extinction, we need to get better at this kind of species rescue operation.

Science, 2026. DOI: 10.1126/science.adw3225 (About DOIs).

John is Ars Technica’s science editor. He has a Bachelor of Arts in Biochemistry from Columbia University, and a Ph.D. in Molecular and Cell Biology from the University of California, Berkeley. When physically separated from his keyboard, he tends to seek out a bicycle, or a scenic location for communing with his hiking boots.

Bringing the “functionally extinct” American chestnut back from the dead Read More »