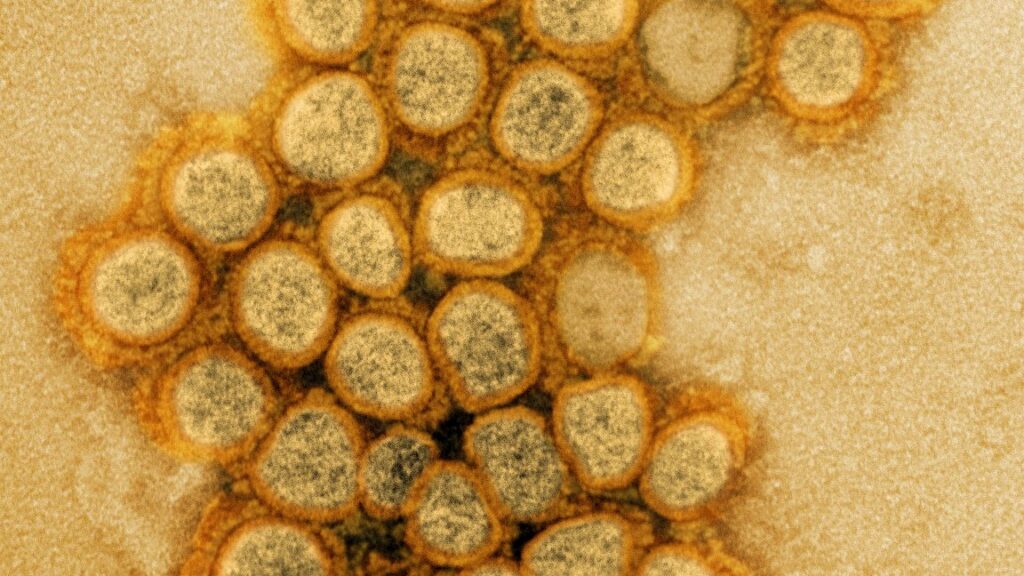

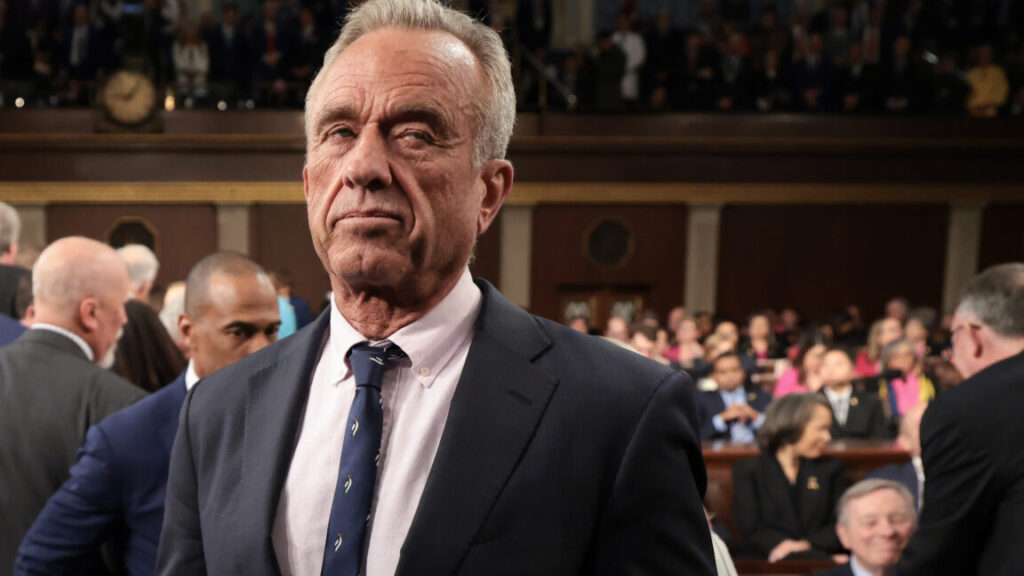

All 17 fired vaccine advisors unite to blast RFK Jr.’s “destabilizing decisions”

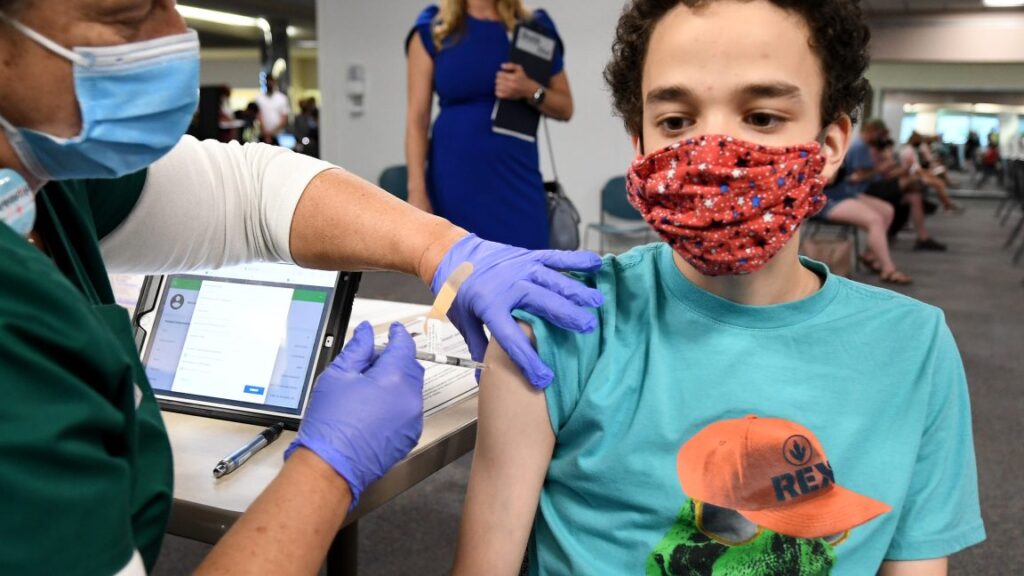

The members highlighted their medical and scientific expertise, lengthy vetting, transparent processes, and evidence-based approach to helping set federal immunization programs, which affect insurance coverage. They also lamented the institutional knowledge lost by the removal of the entire committee and its executive secretary, as well as cuts to the CDC broadly. Together they “have left the US vaccine program critically weakened,” the experts write.

“In this age of government efficiency, the US public needs to know that the routine vaccination of approximately 117 million children from 1994–2023 likely prevented around 508 million lifetime cases of illness, 32 million hospitalizations, and 1,129,000 deaths, at a net savings of $540 billion in direct costs and $2.7 trillion in societal costs,” they write.

They also took direct aim at Kennedy, who unilaterally changed the COVID-19 vaccination policy, announcing the changes on social media. This “bypassed the standard, transparent, and evidence-based review process,” they write. “Such actions reflect a troubling disregard for the scientific integrity that has historically guided US immunization strategy.”

Since Kennedy has taken over the US health department, many other vaccine experts have been pushed out or left voluntarily. Peter Marks, the former top vaccine regulator at the Food and Drug Administration, was reportedly given the choice to resign or be fired. In his resignation letter, he wrote: “it has become clear that truth and transparency are not desired by the Secretary [Kennedy], but rather he wishes subservient confirmation of his misinformation and lies.”

All 17 fired vaccine advisors unite to blast RFK Jr.’s “destabilizing decisions” Read More »