A fentanyl vaccine is about to get its first major test

Vaccine trial in the Netherlands hopes to protect against fentanyl-related overdose and death.

Just a tiny amount of fentanyl, the equivalent of a few grains of sand, is enough to stop a person’s breathing. The synthetic opioid is tasteless, odorless, and invisible when mixed with other substances, and drug users are often unaware of its presence.

It’s why biotech entrepreneur Collin Gage is aiming to protect people against the drug’s lethal effects. In 2023, he became the cofounder and CEO of ARMR Sciences to develop a vaccine against fentanyl. Now, the company is launching a trial to test its vaccine in people for the first time. The goal: prevent deaths from overdose.

“It became very apparent to me that as I assessed the treatment landscape, everything that exists is reactionary,” Gage says. “I thought, why are we not preventing this?”

Fifty times more potent than heroin and 100 times more potent than morphine, fentanyl was first approved by the Food and Drug Administration in 1968 as an intravenous pain reliever and anesthetic. Its potential for abuse was recognized even then, and clinicians could get it only in combination with the sedative droperidol in a ratio of 50:1 droperidol to fentanyl.

Cheap to make and incredibly addictive, fentanyl is now found in street drugs and counterfeit pills, because it boosts their potency and cuts costs. The drug is the biggest driver of overdose deaths in the United States and the leading cause of death for Americans aged 18 to 45.

Naloxone, known by the brand name Narcan, can rapidly reverse overdoses caused by fentanyl and other opioids. Widespread distribution of the medication contributed to a 24 percent decline in US drug overdose deaths in 2024. It works by attaching to opioid receptors throughout the body and displacing the opioid molecules that are attached there.

But a vaccine like the one ARMR Sciences is developing would be given before a person even encounters the drug. Gage likens it to a bulletproof vest or a suit of armor—hence the company’s name. (It was previously registered as Ovax but switched names in January.) “This is something that could completely change the paradigm of how we deal with overdose, because it doesn’t require someone to be carrying the treatment on them,” Gage says.

Opioid vaccines were initially proposed in the 1970s, but after early attempts at heroin vaccines failed, much of the research was abandoned. The modern opioid epidemic has led to a resurgence of interest, with backing from the US government.

ARMR’s experimental vaccine is designed to neutralize fentanyl in the bloodstream before it reaches the brain. Keeping fentanyl out of the brain would prevent the respiratory failure that comes with overdose, which causes death, as well as the euphoric high people get while taking fentanyl.

The basic idea behind ARMR’s shot is the same as any other vaccine. It trains the body’s immune system to make antibodies that recognize a foreign invader. But since fentanyl is much smaller than the pathogens our current vaccines target, it doesn’t trigger a natural antibody response on its own. To stimulate antibody production, ARMR has paired a fentanyl-like molecule with a “carrier” protein—a deactivated diphtheria toxin that’s already used in several approved medical products.

If a vaccinated person encounters fentanyl, antibodies in the blood would then bind to the drug and prevent it from traveling to the brain. Normally, fentanyl molecules can pass through the blood-brain barrier with ease, in part because of their small size. But fentanyl molecules with antibodies attached would be too big to get through. The result? No high and no overdose. The antibody-bound fentanyl molecules would eventually be passed in the urine.

The vaccine is based on work from the University of Houston, with collaborators at Tulane University designing an adjuvant derived from E.coli bacteria to boost the immune response to the vaccine. In rats, the shot blocked 92 to 98 percent of fentanyl from entering the brain and prevented the behavioral effects of the drug. The effects lasted for at least 20 weeks in the rats, which Gage thinks could translate to a year of protection in people.

“The big breakthrough in the past five or six years is the advancement of the adjuvant technology that we’re able to utilize now, which causes an extremely robust immune system response,” he says.

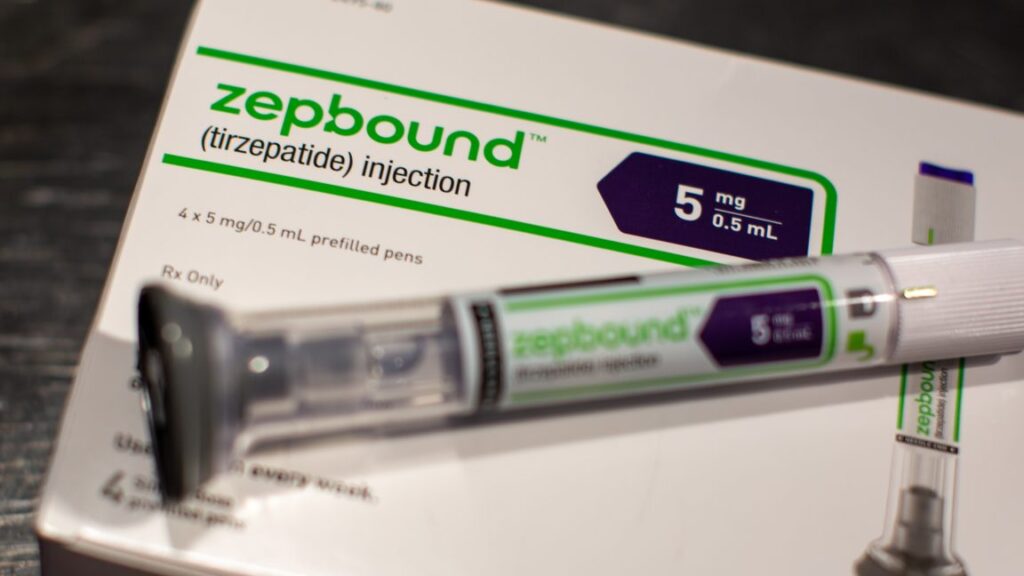

ARMR’s Phase 1/2 trial, which is slated to begin in early 2026, will enroll around 40 healthy adults at the Centre for Human Drug Research in the Netherlands. The first part of the trial will evaluate the vaccine’s safety and determine the best dosage. Volunteers will receive a series of two shots in varying doses, and researchers will measure their blood antibody levels. In the second part of the trial, a small group of participants will receive a medical dose of fentanyl so that investigators can study how well the vaccine blocks its effects. Gage says ARMR chose the Dutch site because of its experience conducting studies on naloxone and nalmefene, another medication that reverses opioid overdose.

The company is testing an injectable vaccine in this study but is also looking into an oral formulation, akin to a Listerine strip, for future trials.

Marco Pravetoni, founder and chief scientific officer of CounterX Therapeutics, has been studying opioid vaccines in his lab at the University of Washington but thinks a shorter-acting monoclonal antibody therapy is more commercially viable right now given the Trump administration’s hostility toward vaccines. The injectable antibody his company is developing is meant to provide monthlong protection against overdose. He says the product is intended for high-risk patients, such as those who are in addiction recovery programs. The Seattle-based company is poised to begin an initial human trial in early 2026.

“We think a month of protection is pretty good in terms of providing a safety net,” Pravetoni says. It would be comparable to Vivitrol, a prescription injectable on the market that’s used to prevent relapse in adults with alcohol or opioid dependence, which lasts for about a month.

One big question facing the development of a fentanyl vaccine or antibody treatment is whether a large enough dose of the drug could skirt by antibodies, making its way to the brain. Sharon Levy, an addiction medicine specialist at Boston Children’s Hospital who has worked on fentanyl vaccines and is one of ARMR’s scientific advisers, says it’s possible. “There’s only going to be so many antibodies,” she says.

In addiction treatment, Levy says there’s always a risk of patients trying to override the effects of a prescribed opioid-blocking medication by taking a high dose of an opioid—which is highly dangerous—but she says this is rare.

Levy and her colleagues have been conducting surveys on the acceptability of a fentanyl vaccine. She thinks a major target group would be teenagers and young adults who may be accidentally exposed to fentanyl when taking street drugs. Individuals with an opioid use disorder who are in active treatment would also be good candidates for vaccination.

“Overall, our experience has been that people would be interested in this,” she says.

Mike Selick, director of capacity building and community mobilization for the National Harm Reduction Coalition, worries that a fentanyl vaccine could block the effects of other opioids, leaving vaccinated individuals with few options for pain medications if they ever needed them.

In animal studies, the University of Houston team found no cross-reactivity with other common opioid-based common pain and addiction treatment medications, such as buprenorphine, methadone, morphine, or oxycodone. But there’s a downside to a lack of cross-reactivity. It means that people could still overdose on other types of opioids—and get high from them.

Gage knows that a fentanyl vaccine isn’t a perfect solution. Even if it works, it won’t end the opioid epidemic or cure opioid addiction. It won’t stop people from seeking out drugs entirely. But it could be another tool for helping to prevent overdose deaths.

“What we’re trying to do is put some innovation and new newfound technology behind this problem,” he says “because I think we’re in desperate need of it.”

This story originally appeared on WIRED.com.

A fentanyl vaccine is about to get its first major test Read More »